Forging a New Art

In the first few months of 1963, the Mona Lisa was seen by nearly two million people in New York and Washington DC. Shipped to the United States on a diplomatic mission – escorted by the French culture minister and received by President John F. Kennedy – the painting did little to assuage Franco-American tension about NATO and nuclear proliferation, but the visit certified Lisa del Giocondo’s status as the smiling face of high art, as iconic as any modern movie star.

Several months earlier, an up-and-coming Pop artist named Andy Warhol, notorious for painting consumer goods, turned his attention to celebrities including Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe. Instead of painting their portraits by hand, he adapted a technique from commercial printing, in which a photographic image could be transferred to canvas by pushing paint through a mechanically-produced silkscreen template. Any photo could be replicated, including those in newspapers, favorite sources for Warhol since they reinforced the relationship of his paintings to mass media. The newspapers might even give him ideas, suggesting popular subjects. And in the winter of 1963, few subjects were more popular than the touring Mona Lisa.

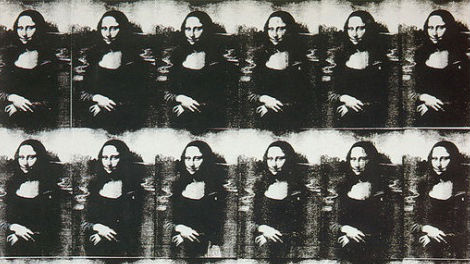

Nobody would mistake Warhol’s Mona Lisas for the Renaissance original. Leonardo da Vinci finessed La Gioconda’s visage with multiple layers of translucent pigment, applied over months with fine sable-hair brushes. Warhol could produce her likeness in mere minutes, a silhouette instantly recognizable as a smear of black paint. He made multiple versions in various sizes. Several were diptychs. His most ambitious was a five-by-six grid called Thirty Are Better Than One.

The title was as sly as his painting was cunning. Thirty are better than one, at least in Warhol’s handling of Leonardo’s portrait. Recognizing that the Mona Lisa had become a celebrity akin to Marilyn Monroe, he proposed that fame was a commodity, and that the endless replication of a celebrity’s face made it so. His industrial process mimicked the mechanism by which people become products, and the end-result revealed the degree to which consumers are active participants, mentally filling in enough details to identify Warhol’s raw silkscreen with Leonardo’s sfumato portrait. In Thirty Are Better Than One, the Mona Lisa is reduced to a pattern, like paisley or toile de jouy: perfectly flat, potentially infinite.

This article is adapted fromForged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age, published this month by Oxford University Press.

Warhol gave Marilyn Monroe the same treatment, screening her face repeatedly from edge to edge of his canvas, yet his repetitions of the Mona Lisa were the most provocative expression of his disquieting vision. Unlike Monroe, whose messy life was extensively chronicled, Lisa del Giocondo was known only by her appearance. A single image was the entire basis of her fame. All surface, no substance, the Mona Lisa was the model celebrity – and an ideal model for deconstructing celebrity in the 1960s.

In art historical terms, Warhol’s copies fall under the category of appropriation, a subgenre dating back at least as far as 1919 – when Marcel Duchamp drew a mustache on a Mona Lisa postcard – in which legitimate artists technically come closest to forgery. Though not produced under false pretenses, works of appropriation art are fundamentally derivative. Like forgeries, they trade on borrowed status. Their significance emanates from an absent original.

In other words, appropriation artists appropriate the forger’s modus operandi for artistic purposes. And almost always, as in the case of Warhol, those purposes are subversive. For instance, in the late 1970s Sherrie Levine began rephotographing iconic photographs by Walker Evans and Edward Weston, calling into question “the notion of originality,” as she told Arts Magazine in 1985. Appropriation is a form of critique, a mode of questioning. Yet Warhol was nearly unique in his ability to question more than merely the work he appropriated.

Thirty Are Better Than One is not really about the Mona Lisa or even about art, but rather concerns the tortuous relationship between culture and media, a relationship beginning to play out in his own life as he became the first meta-celebrity. In a sense, the Mona Lisas and Marilyns and all the paintings that followed were mere props in that lifelong performance, just as counterfeited canvases are only the physical manifestation of a forger’s swindle. Fame was Warhol’s true medium, which he subverted by insisting that he was just like everybody else. “I think it would be so great if more people took up silkscreens so that no one would know whether my picture was mine or someone else’s,” he said in a November 1963 ARTnews interview. (The following year, the appropriation artist Elaine Sturtevant did just that, recapitulating his imagery by borrowing his own silkscreen templates.) By 1968 Warhol was predicting a future in which everyone would be famous for fifteen minutes, a nightmare hybrid of democracy and individualism he personally set out to realize by casting anyone he met, regardless of talent, in his unscripted movies. Like the greatest of conmen, Warhol manipulated people’s desires and beliefs, but unlike Elmyr de Hory or Han van Meegeren, he did it all out in the open, for everyone to see.

Warhol proved that legitimate art could be as powerful as the counterfeit. He showed the extent to which the forger’s art can be appropriated, the mantle of anxiety reclaimed. Yet his achievement also exposes the opportunities squandered by other serious artists, who could potentially have gamed the system but never even tried, preferring instead to produce angst-ridden baubles to be risklessly ogled in museums.

Art has a lot to learn from forgery. If artistic activity online and in the street are any indication, radical contemporary artists perceive the failings of previous generations. Some are attempting to make up for past indolence. One of the most notorious, known only by the pseudonym Banksy, has puckishly taken up where Warhol left off. “In the future, everyone will be anonymous for 15 minutes,” he wrote in 2006 – spraypainting the words on an obsolete TV set – while tauntingly keeping his identity masked.

To this day, Banksy remains known only by his exploits, including his own Mona Lisa appropriation, La Gioconda wearing a yellow smileyface: centuries of Western art distilled to a perfect cliché. In 2004, Banksy smuggled his painting into the Louvre, illicitly attaching it to the wall with double-sided tape. Within minutes it was found and hustled from view by museum staff. However the anxieties it elicited cannot so easily be effaced. Where does culture belong? What can art express? Who’s an artist?

* * *

The Bank of England didn’t believe that J.S.G. Boggs was behaving like an artist when they learned that he was making money. On October 31, 1986, three inspectors from Scotland Yard raided an exhibition of his currency at the Young Unknowns Gallery in London, and placed him under arrest. Though his banknotes were drawn by hand, bearing his own signature as chief cashier, the British government pressed charges under Section 18 of the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act, threatening to end his career with a forty-year prison sentence.

Eventually Boggs was acquitted. His lawyers persuaded the jury that even “a moron in a hurry” would never mistake his drawings for pounds sterling. In truth, the threat posed by his art had nothing to do with counterfeiting. If the Bank of England had reason to be anxious, it was because people knowingly accepted Boggs bills in lieu of banknotes.

Boggs’ project began with a simple exchange. At a Chicago diner one day, he ordered a doughnut and coffee. On his napkin he distractedly wrote the number one, gradually embellishing it until he found himself looking at an abstract $1 bill. The waitress noticed too, and liked it so much she wanted to buy it. Instead of selling, he offered it in exchange for his ninety cent snack. She accepted, and as he got up to leave, she gave him a dime in change.

That became the model for every transaction that followed. Wherever Boggs was, he drew the local currency by hand, and whenever he wanted to buy something, he offered his drawing at face value. In this way, he paid for food and clothing and transportation. However he would not retail drawings to collectors. If collectors wanted to buy, he’d sell them the change and receipt from a transaction, leaving them to locate his drawing and negotiate with the merchant who’d accepted it instead of cash. In that way, he created an alternate economy based on an equivalence between money and art: the inherent uselessness of both that makes the value of each arbitrary.

This correspondence could easily have been tendered as a critique of the art market, and it had been in the past. For instance, in the early 1970s, the conceptual artist Ed Kienholz stenciled ever-increasing sums of money on sheets of paper, each of which he sold successively for the indicated amount, starting at $1 and eventually reaching $10,000. What makes Boggs so compelling is that he reversed the equation. He doesn’t tell us that art is absurd, but breaks out of the museum-gallery complex, leveraging the absurdity of art to question the sanity of finance.

Ditching the museum-gallery complex has boundless advantages, most conspicuously exploited by street artists such as Banksy. The bane of law-and-order fanatics, their misbehavior blasts through barriers of money and power even when those partitions cannot literally be breached: On the concrete wall built by Israeli security to blockade the Palestinian territory, Banksy has illicitly stenciled pictures of small girls frisking armed soldiers, and masked insurgents hurling bouquets of flowers. Violating military regulations to spread messages of peace in a universal visual language, Banksy animates painting as both image and action.

Art behaves in unexpected ways when accepted practices are abandoned. When Shepard Fairey was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design in the late 1980s, a friend asked him how to make a stencil. To demonstrate, he tore a promotional photo of professional wrestler Andre the Giant from a newspaper, slicing away background and shadows with an X-acto, and teasingly adding the line “Andre the Giant Has a Posse”, before using the stencil to make stickers that he pasted up around town. Within days, Fairey overheard people speculating about the message. Was the posse a skate-punk group? A political movement? A cult? The irreducible ambiguity left all options open. A vast diversity of people gravitated toward the image, identified with it, and started making their own stencils and posters of Andre.

Over the next couple decades, image and message were simplified into a blunt black-and-white icon of a brutal face with the words Obey Giant emblazoned beneath. Those modifications, wrought by consensus without any organization, have rendered the project more ominous with time, enlarging and entrenching the giant’s sphere of influence. Whenever Los Angeles or Berlin or Tokyo is hit, spectators and participants alike are impelled to assign meaning to a campaign without any purpose except self-sustenance.

The power of street art, like forgery, is that it cannot be avoided. Spraypaint puts self-expression in the hands of the disenfranchised, who overwrite their neighborhoods with their own text and images. Wheat paste tweaks company billboards into anti-corporate agitprop. (An Apple ad is defaced to make the “Think Different” tagline next to a photo of the Dalai Lama read “Think Disillusioned”.) All of this activity provokes pertinent questions: Who owns a city’s visual space, the corporations who can buy it or the public who lives in it? How can the space be disrupted to make us less complacent?

The operational strategy of street art, where social structures are challenged on their own turf, is often referred to as culture jamming. And as our culture has increasingly moved online, jamming has increasingly followed suit.

One of the first such hacks was perpetrated on December 10, 1998, when the net artists Franco and Eva Mattes launched www.vaticano.org, a near-perfect double of the official Vatican website. The fake online Vatican thrived because few people knew that the Vatican had its own top-level domain – www.vatican.va – and search engines amplified people’s mistake. As a result, untold thousands browsed papal encyclicals that had been lightly modified to promote free sex and drug legalization. Hundreds took advantage of the special offer to have their sins absolved by email.

Franco and Eva Mattes have distinguished their work from appropriation art by referring to it as “attribution art”, a term that aptly aligns them more closely with forgers such as Tom Keating than with straight artists such as Sherrie Levine. At least initially, such work depends on anonymity. On first viewing, Vaticano.org was essentially utopian, subversively foisting a new-and-improved vision of Catholicism on believers, so that the true encyclicals would seem untenably old-fashioned. Then the fraud was revealed, challenging authority from the opposite direction by eroding the credibility of all papal dogma, including proclamations on the official website. (Might vatican.va also be a spoof?) Vaticano.org is a hack on faith.

This double action of fantasy and disillusionment has been used often in net art, and has proven resilient. For instance in 2011 the new media artists Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev invented a gadget that allows them to hijack the wifi signal in a library or internet cafe, and to remotely edit the content of news sites such as nytimes.com so that anyone in the room browsing The New York Times on a wireless device sees modified headlines. Since the hack is strictly local, the news sites are never aware of the override. And since the appliance is open-source – with blueprints freely provided online – there’s a chance the news has been hacked at any hotspot worldwide.

Oliver and Vasiliev dubbed their work Newstweek and on the project website describe it as “a tactical device for altering reality on a per-network basis”. Like the modifications to the Vatican website, their alterations often take the form of wishful thinking. (In one case, they had Wikileaks founder Julian Assange being nominated U.S. Secretary of Defense.) But the differences between Newstweek and the Mattes’ attribution art are as significant as the similarities. Here the content is decidedly secondary to the concept. The undercurrent of anxiety derives from the fact that the hack is not isolated – unlike Vaticano.org – and responsibility cannot be traced to any single source.

Newstweek is the reductio ad absurdum version of citizen journalism, in which everyone is an autonomous news organization. It’s an uncontrolled experiment in the democratization of information, in which anyone can potentially be a participant, voluntarily or not.

Precisely where the art resides, and who are the artists, are questions without definitive answers in the case of Newstweek, especially since the open-source plans allow anyone to modify everything, from the headlines to the capabilities of the device. In that respect, Newstweek is the online analogue of Obey Giant. All that can be said of such projects is that they disrupt the status quo for no purpose other than to question it. To appropriate a term from Immanuel Kant, they are animated by Zweckmäßigkeit ohne Zweck – purposeful purposelessness.

* * *

Zweckmäßigkeit ohne Zweck is a perfect description of art. Purposeful purposelessness is appealingly broad, encompassing activities that aren’t conventionally artistic, such as the chess matches favored by Marcel Duchamp. Yet Zweckmäßigkeit ohne Zweck is also informatively narrow. Art forgery is not purposeless.

That is why forgers cannot replace artists, but can only offer inspiration. Art must take up the forger’s means without the forger’s goals, to work on the far side of legitimacy without the limitation of making a point or a buck.

The far side of legitimacy is not necessarily illicit. To act on our anxieties, art must break mores. In some cases, those mores may be enforced by law, yet the full range of human behavior is beyond the imagination of legislators and judges, whose work is essentially reactive. Artists can experiment with possibilities outside our current reality.

Given the unlimited potential of experimentation, it comes as no surprise that the strongest provocations in the 21st century take the form of pure research, more often associated with the sciences. Artists such as Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr of the collective SymbioticA work in a fully-equipped laboratory, where they have grown frog steaks in petri dishes using standard tissue-culturing techniques. Their Disembodied Cuisine paralleled research by NASA – where scientists were investigating protein sources for long-term space flight – but broke rank with staid scientific protocol in 2003 when Catts cooked and served his lab-grown steak at a dinner party. The frog from which the muscle cells had been cultured was still alive, and present to witness the feast. The distinction between life and death has never seemed more tenuous.

And yet more incendiary permutations on Disembodied Cuisine – such as disembodied cannibalism – might roil society at any time. Like the coding behind Newstweek, SymbioticA’s methods are all open-source, and actively spread through workshops led by Catts and Zurr.

A salient feature of experimentation, this free license to replay and remix is central to the scientific method. Yet in professional scientific circles, the potential to profit from spin-off technologies encourages secrecy and intellectual property protection.

The open exchange of ideas has been rebranded as piracy. To the extent that enlightenment principles are the ideals of science, artists such as Catts and Zurr act more scientifically than scientists.

One especially guarded realm of scientific research is genetics, which can inspire lucrative pharmaceuticals, food crops and even flowers. In 1992, the Australian company Florigene patented a sequence of petunia DNA that could be implanted in carnations and roses to make them blue. These genetically modified organisms (GMOs) were greenhouse-cloned and sold to florists pre-cut, ensuring that the Florigene holding company Suntory was the only source of the vastly popular flowers for nearly two decades. Then in 2009 the artists Shiho Fukuhara and Georg Tremmel tested the premises of this scientific monopoly. They reverse-engineered the plants, and released blue carnation seed into the wild.

As Fukuhara noted on the artists’ website, they were giving the plants a “chance of sexual reproduction” denied to them by Suntory. Living this wild new life, the flowers infringed on Suntory’s intellectual property by making countless unauthorized copies of their patented DNA. The pirated flowers became pirates in their own right just by attempting to live a natural life. Non-modified carnations were potentially also implicated by cross-pollination. The intellectual property protection of life was put to the test by the disobedience of flowers.

When Fukuhara and Tremmel exhibited their reverse-engineered carnations at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Austria, local officials required that the plants be locked behind bulletproof glass, under constant surveillance by security guards. The precaution had nothing to do with patent law, and everything to do with anxiety about GMOs that might mix with the native flora of Linz. The boundary between natural and artificial is permeable; that’s why the protection of guards and bullet-proof glass was deemed necessary by the Linz government. But the permeability inclines less literal minds to explore the inevitably hybrid future wrought by all biotechnology. Releasing blue carnations is an experimental exploration of that future. If it is uncontrolled and irresponsible, that is because the subject under examination is messy and perilous.

Zweckmäßigkeit ohne Zweck is the ultimate artistic license. Mixing disciplines and refusing to be disciplined, purposeful purposelessness calls everything into question. Full exercise of that license, never even a consideration for forgers, was beyond the capacity of Elaine Sturtevant and Andy Warhol, even Marcel Duchamp. If it has ever been achieved, it was accomplished out of pure curiosity by the man who first made the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo’s curiosity was deeply subversive. His human dissections were deemed acts of desecration, and condemned before Pope Leo X. His astronomical observations would also have caused trouble had they been more fully developed. Though he never claimed that Earth orbited the Sun, he deduced that the world would appear from the Moon as the Moon did from Earth: The impression of motion was relative to where the viewer stood. More generally, Leonardo rejected authority, ancient and contemporary. He called himself a disciple of experience, but he was equally an apostle of investigation.

If art is good for anything, it’s a means of opening the mind. The time has come to dump the Mona Lisa and dismiss Leonardo the talented painter. Fearless artists must resurrect and reinvent Leonardo the renegade scientist.

Adapted from Forged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age, published this month by Oxford University Press.

# # #