Drilling Holes in Heads: A Brief History

This post originally appeared in the Newton blog on RealClearScience. Read the original here.

Take a moment to rub the top of your skull. Pretty smooth and sturdy, right? What a great place to store 86 billion neurons! Aren’t you glad there are no holes in it?

A quarter-inch of solid bone (0.28 inches for women), a thin layer of skin, and — with any luck — some hair is all that separates the outside world from your precious brain, the nucleus of your nervous system and the center of your psyche. The protection is sufficient for the hazards of everyday life; an occasional clunk to the noggin’ is of little to no concern. But with a little motivation — and the aid of a drill or pick — one could easily unlock the squelchy pink organ encased within.

This fact was not lost on our ancestors. Medicine men of pre-Inca, Peruvian civilizations would often use their sacred knives to puncture the skulls of tribe members afflicted with serious headaches. Like letting the air out of a brimming balloon, the procedure was thought to release evil, pain-inducing spirits locked within. Of course, at the same time it let in dust particles and microbes, which often led to infection. The spirits appreciated the fresh air, though.

Across the Atlantic, Roman physicians developed an array of small, yet terrifying instruments to perforate the cranium. In lieu of blunt force, the gadgets simply needed to be twisted and rotated to gradually chisel away the bone.

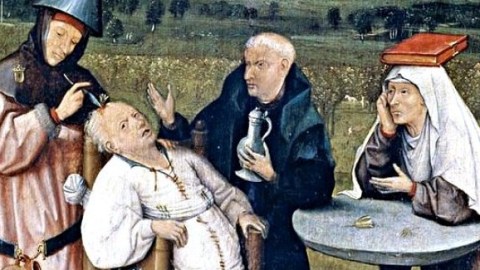

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, doctors built and improved upon the Roman designs. A common “trephine” instrument could be affixed atop the skull, three stands holding it in place. All the user had to do to perform a lobotomy was screw a pointy metal object into the patient’s head — just like uncorking a bottle of wine!

Of course, the lobotomy wouldn’t really take scientific shape until the late 19th century, when Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt formally theorized that removing sections of the cerebral cortex could alter a person’s behavior. He was right. Of the six schizophrenic patients Burckhardt operated on, two supposedly showed limited changes, two became “quieter,” one died, and one improved. By his glass-half-full calculations, that indicated a success rate of roughly 50%. But many of Burkhardt’s colleagues disagreed, and he discontinued his brain tampering.

Still Burkhardt’s experiments gave “lobotomy” a definition: the cutting or scraping away of most of the connections to and from the prefrontal cortex (which is an executive area that shapes one’s personality). Before, doctors weren’t really lobotomizing, they were simply poking holes in skulls and prodding around a bit.

About 30 years later, in 1935, the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz developed the procedure for the modern lobotomy. His process was as follows: First, the patient would be anesthetized and holes drilled into the skull. Then, pure alcohol was poured through the holes onto the white matter beneath the frontal area, thus severing the nerve fibers connecting the frontal cortex and the thalamus. (Later on, Moniz would replace the alcohol, instead simply rubbing the edge of a knife over the white matter.)

With his partner, Almeida Lima, Moniz operated on at least 20 patients, reporting that patients were more “calm and manageable but their affect more blunted” in the wake of the operations. In the American Journal of Psychiatry, Moniz brusquely described his achievement, one that would garner him the 1949 Nobel Prize in Medicine:

“Following this exposition I do not wish to make any comment since the facts speak for themselves. These were hospital patients who were well studied and well followed. The recoveries have been maintained. I cannot believe that the recoveries can be explained upon simple coincidence. Prefrontal leucotomy is a simple operation, always safe, which may prove to be an effective surgical treatment in certain cases of mental disorder.”

“Always safe” was a bit of an exaggeration. Around a third of patients actually proved to be worse off after the procedure. Still, around 60,000 lobotomies were performed in the U.S. and Europe between 1936 and 1956. Some doctors, like the American neurologist Walter Freeman (pictured above), could perform them in a mere five minutes. Many considered the lobotomy a risky, yet viable, and even kind alternative to the straitjackets and padded rooms of the insane asylum, where over 450,000 mentally ill Americans were “hospitalized” in 1937. Drilling holes in heads eventually gave way to pharmaceuticals, which, despite their potential side effects, are far more effective at treating serious mental problems and less dangerous.

Primary Source: Faria MA. Violence, mental illness, and the brain – A brief history of psychosurgery: Part 1 – From trephination to lobotomy. Surg Neurol Int [serial online] 2013 [cited 2013 Jul 18];4:49. Available from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2013/4/1/49/110146