Downton Abbey, the Art Exhibition?

The appeal of the British drama/high-class soap opera Downton Abbey for American audiences has long been a subject of great speculation. Simon Schama called the show “cultural necrophilia” for bringing to life a time he saw as long dead and rightfully so for all its elitism and iron-clad class consciousness from the bottom up. A new exhibit at the Yale Center for British Art taps into American Downton-mania, but critiques as it celebrates. Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century, which runs through June 2, 2013, collects the high fashion, flashy jewelry, and dazzling portraiture of a too-short age squeezed between two eras that make us today ask both too little and too much of the Edwardians. Is this “Downton Abbey, the Art Exhibition,” or is it much more?

The Edwardian Age fits neatly into a single decade between the death of Queen Victoria (who took her eponymous age to the grave with her) and the crowning of her son, King Edward VII, in 1901 and when Edward took his own age to the grave in 1910, before the Titanic, World War I, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, and a litany of other disasters threatened to sink humanity itself. Between the Great Victorians and the Great War, according to the history books, the Edwardians luxuriously languished, lacking both the high morals and culture of the preceding age and the high drama of the following one. Edwardian Opulence stresses the luxury, but questions the languishing.

If you want the glitz of Downton Abbey, Edwardian Opulence won’t disappoint. A bell push festooned with a sapphire, a ruby, an amethyst, a moonstone, and a diamond by Carl Fabergé of the famous Fabergé eggs seems the logical way Lord Grantham would call Carson. (A too brief selection of items from the show can be seen here.) An ostrich feather fan jazzed up with silver and diamonds once belonging to Mrs. James de Rothschild would look just as natural in Lady Mary’s pale fingers. Period clothing appears alongside photographs of the well off sporting similar wear. And that’s all before you even consider the clothing and accessories in the portraiture. Just as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity argues that you can’t separate that era’s art and fashion, the same can be said for Edwardian Opulence.

John Singer Sargent, perhaps the most desired portraitist of the period, claims center stage with his typically masterful, romantically idealizing portrayals of Sir Frank Swettenham and Lady Evelyn Cavendish. Giovanni Boldini’s famously flowing painting style transforms Mrs. Lionel Phillips, wife of a diamond magnate and herself a forward-looking collector of modern art, into a swirling creature of fabric, with her pretty face at the center of the storm. Photographic portraits of artists and intellectuals such as Henry James, Ezra Pound, W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, and even Sargent by Alvin Langdon Coburn demonstrate how alive this “languishing” age really was in the brief time it existed.

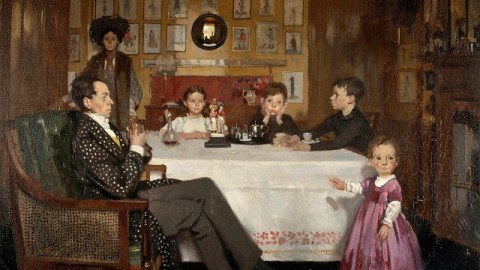

Of all the portraits, however, the one that caught my eye, beyond all the glitz and glamour, was William Orpen’s simple 1907 painting, A Bloomsbury Family. You can almost hear the sighs of the family burdened by all the normal nuclear family stresses as well as the pressures of position in a world fixated on position regardless of the march of modernity. Orpen, an Irishman, worked in London among the fashionable Edwardians, but he never forgot his roots, supporting the “Celtic Revival” that added a cultural dimension to the political struggle for Irish independence from English rule (embodied in Downton Abbey by chauffeur-turned-journalist-turned-family-member Tom Branson). A Bloomsbury Family feels like an English family’s struggle for independence from Edwardianism itself. I only knew Orpen previously from a self-portrait at the Met, also known as Leading the Life in the West, which shows Orpen admiring himself in a mirror wearing the fashionable clothes of a young Edwardian of the West End of London. Orpen later won knighthood for his paintings depicting the heroism and the horrors of World War I, an experience that changed him thereafter. The inclusion of artists such as Orpen and Walter Sickert (through his Camden Town Murder, aka, What Shall We Do About the Rent?, aka, Is Walter Sickert Jack the Ripper?) brings in an outsider’s view among these incestuously Edwardian insiders that makes for much more drama than even your average Downton plot twist.

The inclusion of sound recordings from the period reminds us of just how modern the Edwardians were. Listening to them makes the century between us melt away. But to listen to those recordings is to hear the sound of the Edwardians’ own nostalgia for a time they saw slipping away before their very eyes. Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century humanizes the people in the portraits and allows us to clasp hands imaginatively with the bejeweled fingers of these people on the verge of carnage on a scale never seen before but, sadly, seen too often since. There’s a prelapsarian innocence in both Edwardian Opulence and Downton Abbey that we, Americans and British, cling to desperately because we know the tragic fall soon to come. Edwardian Opulence may be more “cultural necrophilia,” but, like Downton Abbey, it’s a beautifully bitter ride to oblivion.

[Image:William Orpen, A Bloomsbury Family, 1907, oil on canvas, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Presented by the Scottish Modern Arts Association 1964.]

[Many thanks to the Yale Center for British Art for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century, which runs through June 2, 2013.]