Do We Learn to Love Bad Art?

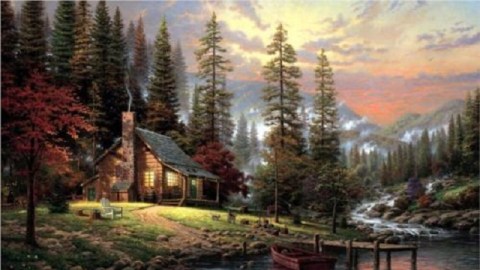

Does great art last because it is great or is it great because it lasts? Do works find a place in the canon by familiarity, like a ubiquitous tune you can’t shake, or do they play on through sheer merit? A recent study in the British Journal of Aesthetics by Meskin et al titled “Mere Exposure to Bad Art” examines the effect of “mere exposure” on how people perceive art. After showing students slides of “good” art (landscapes by 19th century British painter John Everett Millais) and “bad” art (works by the trademarked “Painter of Light” himself, Thomas Kinkade) at differing frequencies, the researchers suggest that looking at bad art more often makes us hate it even more (or so they hope). But is it still possible for us to learn to love bad art?

Meskin and associates began their study as a response to a 2003 study by James E. Cutting titled “Gustave Caillebotte, French Impressionism, and Mere Exposure” in the Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. Cutting showed 66 images from Impressionist artists (including works by Gustave Caillebotte, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley) that he felt depicted the “high canon of Impressionism to its base corpus.” Cutting showed the paintings at frequencies ranging from more than 100 to less than 10. When he later showed the paintings in pairs and asked which the participants preferred as better, 59% of the time the viewer chose the painting they had seen more frequently. From those results, Cutting concluded “that artistic canons are promoted and maintained, in part, by a diffuse but continual broadcast of their images to the public by museums, authors, and publishers. The repeated presentation of images to an audience without its necessarily focused awareness or remembrance makes mere exposure a prime vehicle for canon formation.” In other words, Cutting believes that the repeated “broadcasting” of a work of art by the canonizing system makes us believe (at least in part) that the work is worthy of the canon. We don’t get to chose whether it’s good or not. The choosing is done for us. And then the choice of others becomes our “choice” by sheer repetition. Or, as Joseph Goebbels would have put it, “If you repeat alie often enough, it becomes the truth.”

Meskin et al decided to address these troubling, cynical assertions by adding to the experiment a greater variety of quality—a clearer “good” versus a clearer “bad.” Whereas Cutting chose a fairly level playing field (Sisley’s no Monet, but he’s no slouch either), Meskin’s team decided to pit the paintings of critically acclaimed Millais versus those of critically lambasted Thomas Kinkade. Fifty-seven British students were shown 60 slides (48 paintings by Kinkade and 12 by Millais) and asked which they “liked.” “Our decision to measure liking rather than goodness,” they write, “was based on the assumption that preference is expressing what is taken to be the grounding of aesthetic appraisal, and a concern that a measure of goodness might suffer from ambiguity. Participants might confuse (or run together) overall artistic quality or worth (‘good art’) with a judgement of technical merit (‘good painting’).” In other words, a respondent might equate “good” with “better than I can paint right now,” so the researchers used the less ambiguous (but still problematic) concept of “liking.”

Meskin et al found that the more that people saw paintings such as Kinkade’s A Peaceful Retreat (shown above), the less they liked them. In contrast, repeated viewings of Millais’ paintings led to little to no change. Funny enough (but probably not funny to Millais), participants actually liked Kinkade’s paintings slightly more than Millais’ paintings at first, but “mere exposure” eventually pulled Kinkade’s ratings down as Millais’ held steady. The researchers venture a guess that repeated viewings allowed the participants to see just how poor Kinkade’s paintings are, “[j]ust as the first sip of a pint of poorly made real ale might not reveal all that is wrong with it (but a few drinks will reveal how unbalanced and undrinkable it really is).” Once the initial inebriation of Kinkade’s eye-catching effects wears off, the viewer sobers up enough to see the kitsch beneath them. Meskin’s team points to the fact that Millais initially loses to Kinkade as proof that repeated exposure has the power to change minds for the better.

Meskin et al acknowledge that beauty is ultimately in the eye of the beholder, citing Kinkade’s enduring posthumous popularity in America versus his almost universal rejection by the British. (Reading the researchers heap up the evidence of Kinkade’s crappiness was quite amusing.) Maybe their results would have been different on an American campus. Without going too far out on a limb, Meskin et al claim only that their study results “suggest that something other than mere exposure plays a role in judgments of paintings. It could be ‘quality assessment’, or it could be something else.” Perhaps they undervalue the power of repeated (maybe even enforced?) exposure that Cutting argues for in his study, but Meskin et al at least strike a more hopeful blow for those who want to believe that good art prevails because it is somehow good. Every starving, Van Gogh-aspiring artist out there dreams of posterity someday discovering what their contemporaries couldn’t. To leave the canon to the publicity hounds (e.g., Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and others whose names appear in print undeservingly often) would be a sad, if unavoidable, truth.

[Image:Thomas Kinkade. A Peaceful Retreat, 2002. Image source.]