DNA Collection is a Feminist Issue

In 2003, a man broke into Vonette W.’s house in the middle of the night, wearing a scarf to cover his face. He held a gun to her head and raped her. After the crime Vonette called the police, and forensic evidence was collected at a nearby hospital. The evidence didn’t match with anything in the Maryland DNA database at that time.

Six years later, Alonzo King was arrested on assault charges. In the course of his arrest, police took a swab of saliva from his cheek, and his DNA came up as a match in the Vonette W. rape case. King was convicted, and appealed, on grounds that this was a violation of his Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches.

This week, the Maryland court of appeals agreed with King, and reversed the conviction as based on “fruit from a poisonous tree:” The DNA sample from his saliva was an unwarranted violation and intrusion on his privacy.

Similar cases, which challenge state DNA collection laws (in this case, Maryland’s 2003 DNA Collection Act, which allows officers to collect DNA samples from people arrested), are making their way through state court systems. Maryland’s attorney general will probably appeal this decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Both the dissent and the majority agree on three important things: What happened to King was indeed a “search;” the legal touchstone for whether it was a legal search under the Fourth Amendment is a standard of “reasonableness.” Third, the well-established test of “reasonableness” in a Fourth Amendment case is that the court must “balance the privacy interests of the individual searched against the legitimate government interests promoted by the search.”

Of course, reasonableness and balance don’t come in Standard Weights and Measures. Their determination requires human interpretation, and both sides have legitimate interests to protect.

The dissent argues that the majority arrives at its decision by “overinflating an arrestee’s interest in privacy and underestimating the State’s interest in collecting arrestee DNA.” “The majority’s application of the test could not be more wrong.”

The majority argues that King has a presumption of innocence, and hence a greater privacy interest than a convicted felon. The dissent agrees that King enjoys a presumption of innocence, but that that has nothing to do with his expectation of privacy once he’s arrested. At the moment of arrest, a person is subject to a lot of permissible intrusions on his privacy, including strip searches.

The ninth circuit court of appeals upheld a DNA Collection statute in 2012, commenting that swabs for all adults arrested for felonies are “little more than a minor inconvenience…and substantially less intrusive” than other types of approved intrusions visited upon arrestees.

A Supreme Court ruling from 1966 even upheld the drawing of blood from an arrestee—much more invasive—as “commonplace” and a procedure “involving “virtually no risk, trauma or pain.”

His risk, trauma and pain, or “intrusion upon privacy and bodily integrity,” of course, is nothing compared to rape.

And that point is relevant: The “intrusions” that the court must balance on the scale to determine reasonableness in this case couldn’t be more lopsided.

On the one hand, you have a two-second swab of saliva in a cheek in a police station. On the other hand, you have a man wearing a mask, breaking in to a 53-year-old woman’s own home in the dead of night, and raping her.

It seems that the gross intrusion of the crime would significantly weight the scale of reasonableness toward the “legitimate interests” of the State to collect DNA to solve cold cases of rape and prevent future assaults, and away from the suspect’s right not to have his “bodily integrity” violated by a non-invasive procedure performed in a context of already-diminished privacy expectations.

But one reason the majority comes to a different interpretation of “reasonableness” is because they envision DNA collection as a more sinister and omnipotent technology than a mere procedure for identification.

A DNA sample contains “much more than a person’s identity,” they argue. Although the Maryland Act only authorizes DNA for identification purposes, the majority writes that it can’t “turn a blind eye to the vast genetic treasure map that remains in the DNA sample retained by the State.”

A vast genetic treasure map. That sounds scary to anyone who’s seen Gattaca. I’m picturing my DNA displayed on one of those faux-aged treasure maps, with clues written conveniently in English, little Post-its to direct us, and big stars to indicate, “This is the Spot!”

But does the techno-paranoia and Big Brother dystopia that murmurs under the majority’s ruling square with reality?

Not really. The Maryland act categorically prohibits the “plundering” of this treasure map, without exception, and would punish severely any disclosure from a DNA profile.

Sure, the law can get broken. I guess that’s the fear haunting the Majority’s opinion. Any legally permissible act or tool of law enforcement might be illegally used. If police officers carry clubs and tear gas, they can use them to beat Rodney King or to assault Occupy Wall Street protestors on a campus.

The fact that they used a law enforcement tool illegally doesn’t lead to the conclusion that the tool, ipso facto, can’t be used legally.

More significantly, the procedure in question can’t actually disclose intimate information that a genetic pirate would want to plunder.

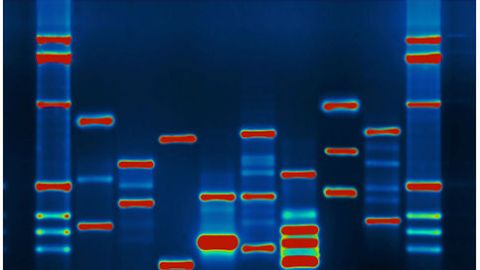

The 13 loci used in this DNA testing are non-coding but “hypervariable.” They don’t reveal any information about human attributes such as height or disease susceptibility, but they vary so much that they work well for identification.

So, on one side of the scale in the balance assessment sits an extremely minor “invasion” of the body, and a hypothetical concern that DNA could be abused. On the other side sits an extremely major bodily invasion—rape—and an all too literal and factual injury to a woman’s body, integrity and privacy.

Yet this decision gives more weight to the defendant’s rights. Theoretical harms against the suspect and minor invasions of his body are vividly, hyper-sensitively imagined, while intrusions upon the body and integrity of the rape victim, who is at the silent heart of the case, are imagined not at all, or handled with deficient, hypo-sensitivity.

Were these non-hypothetical violations appreciated more vividly, then the government’s “legitimate interests” in DNA collection might have been felt more keenly than the exquisitely-imagined but hypothetical dangers of DNA sample abuse.

DNA collection has been valuable in solving cold cases of rape and sexual assault, so this ruling is troubling not just for this individual case, but generically. Of 462 database-aided arrests in Maryland, 130 (28%) were for crimes of rape or sex offenses.

This decision sits at the cultural intersection of distrust for the government and tech-paranoia, and a resurgent disrespect for the integrity of women’s bodies (transvaginal probes are a state-mandated “violation of bodily integrity,” if ever there was one).

It’s not difficult at this intersection to imagine a thumb on the scales, even if just subconsciously, giving more weight to the miniscule “invasion of bodily integrity” of the suspect and to the hypothetical, theoretical dangers of the illegal use of his DNA sample, than to the profound “invasion of bodily integrity” of the rape victim, and her all too real, embodied, and factual injuries.