Can a Comic Book Make Economics—the “Dismal Science”—Fun, and Understandable?

“It’s the economy, stupid!” James Carville crowed throughout the 1992 presidential election, and has pretty much continued crowing since. What do you do when you know it’s the economy that matters, but you’re feeling stupid about how it all works? Do you plunge headfirst into Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations? Do you blow the dust off your college macroeconomics textbook that you couldn’t stand reading even for a grade? Author Michael Goodwin feels your pain, because he found himself in the same predicament—a voting American citizen faced with the truth that he didn’t know anything about the policies he was voting for. Fortunately, Goodwin had done the legwork of untangling the web of economic knowledge for us. Even better, with the help of illustrator Dan E. Burr, Goodwin delivers that knowledge in the accessible format of the graphic novel. Economix: How and Why Our Economy Works (and Doesn’t Work), in Words and Pictures eliminates feelings of stupidity in the face of economic-speak while demonstrating how it really is the economy and why nobody should be stupid about it.

“Everyone has questions about the economy,” Goodwin begins his explanatory preface, with his soon to be very familiar face among the questioning crowd. Goodwin hits the books and goes back to the original sources of economic thought—Smith, Ricardo, Keynes, Marx, and friends. As a big picture began to take shape in his mind, Goodwin realized that “while the whole picture was complicated, no one part of it was all that hard to understand.” Hoping to make those pieces as understandable as possible, Goodwin chose the “most accessible form I knew: comics.” Some may dismiss the format as kids’ stuff, but the realities inside Economix and the purpose behind it are for the real grownups. “We’re citizens of a democracy,” Goodwin explains. “Most of the issues we vote on come down to economics. It’s our responsibility to understand what we’re voting about.” Fortunately, you’ll may never accept democracy’s responsibility in as fun a way as Economix allows.

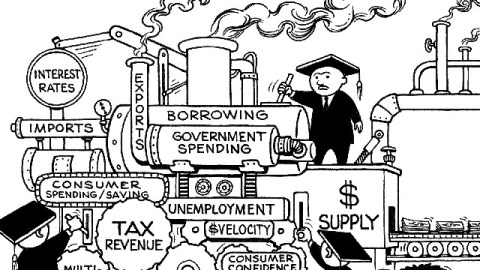

Goodwin arranges the book in a roughly chronological way, skipping forward or backwards in time only when necessary to make important connections. The geographic focus centers on the United States, because Goodwin’s an American and that’s his main concern, but Economix spans the globe and travels to Europe, Russia, Asia, India, and elsewhere, especially after technological advances make the world smaller and more interdependent. Burr’s illustrations make what Thomas Carlyle called “the dismal science” after Malthus’ grim economic prognosis not just as visually clear as Goodwin’s prose, but also good fun. You’ll never think of taxation or “bracket creep” the same way after watching Burr’s embodiment prance across the page.

Goodwin writes in a clear, vibrant style. He gives you not just the basics, but also the forgotten or misremembered bits of economic history that muddle it for so many of us. For example, Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” appears, but Goodwin also highlights Smith’s “big forgotten message”: “Beware of capitalists!” David Ricardo emerges as “possibly the most important person nobody’s ever heard of” thanks to his fathering of classical political economy—the seemingly parallel universe in which economists build abstract economies that bear little to no resemblance to real world finances. (Burr helpfully places these economists in academic gowns and hats [as shown above] to remind you of these economists’ theoretical, ivory tower approach.) Reagan– olatry takes a beating as Goodwin tears down the two central myths of Reaganomics (small government and lower taxes) in his characteristic logical, crystal clear, and unapologetic way.

Goodwin wears his ideologically biased heart on his sleeve. The bent throughout Economix is liberal, but reality, Goodwin would agree, has a well-known liberal bias. A cartoon Goodwin guides you through the ages all the way up to today, so the human element never disappears in a sea of abstractions and cold calculations. “Economics isn’t chemistry—it deals with the infinite complexity of human behavior, not with rigid laws,” Goodwin responds to his critics. All books on economics contain bias. Some hide it better than others. Goodwin embraces his. Not only does he embrace it, he challenges you to fact check it. In addition to nearly 300 pages of illustrated, opinionated economics, Economix comes with a glossary, guide for further reading, and index (rare exotic animals for a graphic novel) as well as full references and notes online for the most rabid of naysayers.

You’ll come away from Economix with a slew of newly understood concepts, from mixed economy to stagflation, but the most important thing you’ll come away with is a newfound confidence in your ability to understand how the economic world works for and often against us. After Economix, you’ll be able to delve into writings by Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, or other current economists trying to make sense of today’s world. Before the chapter titled “Things Fall Apart,” Goodwin quotes John Maynard Keynes saying in 1930 that “We have involved ourselves in a colossal muddle, having blundered in the control of a delicate machine, the working of which we do not understand.” Just when the world seems to have fallen apart thanks to the economy, Goodwin and Burr’s Economix comes along to give us some understanding of the immense, yet still “delicate machine” that controls our world so that we can be the rulers with our votes and not the uninformed (or disinformed) ruled.

[Many thanks to Abrams Comic Arts for providing me with the image above from and a review copy of Economix: How and Why Our Economy Works (and Doesn’t Work), in Words and Pictures, written by Michael Goodwin and illustrated by Dan E. Burr.]