Being Bourgeois and Bohemian Just Isn’t Enough

So what young conservative blogger/essayist would you recommend to challenge those who believe they’re smarter than every conservative in the world? Well, SAM GOLDMAN. Sam’s not the only one by far, but he’s my choice for today.

After all, who else is outing “the spiritual crisis of the bourgeois bohemians,” at least today?

The very incisive descriptor “bourgeois bohemian” is what made David Brooks famous as a social analyst. It’s a more accurate description of most members of our educated and sophisticated elite today than when Brooks coined it well over a decade ago.

America used to have the tragedy of being divided, our intellectuals thought, into the bourgeois and the bohemians. The bourgeois had the habits and skills required to make big money. But they didn’t know how to use it. The bohemians had the secret of living well, but they didn’t have enough money to pay the rent.

But along came the 1990s, Brooks observed, which were kind of a synthesis of the bohemian 1960s and the highly productive 1980s. The result was the bourgeois bohemian. Prosperous and highly educated Americans came to know both how to make money and to spend in edifying, tasteful, enjoyable, highly self-fulfilling ways. Due to their sophisticated taste, all the amenities of American life got better or more aesthetically pleasing—from coffee to homes and neighborhoods to vacations to restaurants to music. (Well, I’m not so sure about music.)

Being bourgeois bohemian isn’t quite a synthesis, because being bourgeois comes first. The insight is that you have to deploy the brains, skills, and habits required to be productive, before you have the money required to satisfy your high-order and high-status desires. A real bohemian, of course, would laugh at all the boring thinking required to get priorities that straight. A real bohemian wouldn’t give a fig about “calculating probabilities” when it comes to risk factors or do anything but laugh at transhumanists or personal trainers. Real bohemians (I want to say “such as me,” but I’m too boring) notice that the best introduction to the ideology of bourgeois bohemianism are the blogs and such of the Harvard Business School. (Actually, that can’t be right. What real bohemian would have anything to do with the Harvard Business School? It’s also true that real bohemians couldn’t possibly spend much time at all online.)

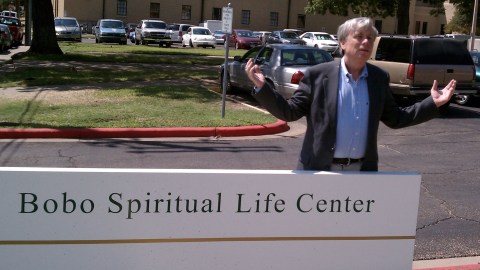

As Sam says, bourgeois bohemians have an impoverished spiritual life. They’re all about post-Christian, fuzzy, feel-good, stress-relief spirituality, thinking they’ve evolved beyond the repressive dogmatism of religion. One sign of their impoverishment is they really don’t think they have demanding, profoundly sacrificial personal duties to others, to their fellow citizens or creatures. The virtues of charity and generosity have morphed into the non-species specific feeling of “empathy.”

Finding time to be both bourgeois and bohemian is hard enough. And somehow time also has to be found for a small family. There’s no personal time (no me time) left for the unfortunate or even to think seriously about my contribution to growing, increasingly pathological, and somewhat undeserved inequality of our time. For myself, I tend to think that the loneliness crisis is scarier than the inequality crisis, without denying for a moment that they’re somewhat related.

The bohemians were right that being bourgeois couldn’t possibly be the point of life, even if they were wrong to think bourgeois virtue is an oxymoron. But higher, of course, than being either bourgeois or bohemian is being a citizen, a saint, a parent, a friend, or any kind of “voluntary caregiver.” Both bourgeois and bohemian, finally, are loose synonyms for selfish. A certain amount of selfishness is required to be responsible and maybe even to be happy, but it can’t be all there is to being responsible or happy.

Sam rightly marvels at the self-indulgent bourgeois-bohemian ignorance of New Yorker writer George Packer about an alleged paradox that characterizes 21st-century America: “So how can this be the best of times for gays, sufferers from cardiovascular disease, African American politicians, TV fans, ambitious women, and so on, but among the worst for the urban poor, agricultural workers, and overleveraged homeowners? Packer can’t quite figure it out.”

Why is the allegedly savvy Packer so “obtuse” that he can’t figure out the cause of one of the most overwhelming social facts of our time? It’s because he’d have to think about the bourgeois-bohemian spiritual crisis! Read Sam’s essay, and I’ll say more in my next post.