Are the “Real” Wyeths Hiding in the Sanderson Museum?

There may be no American artist so linked with specific places and the history of those places as Andrew Wyeth. Wyeth spent his summers in Cushing, Maine, but the other three seasons found him in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. When Andy’s father, the artist N.C. Wyeth, first came to Chadds Ford to study with Howard Pyle, the native New Englander found himself ignorant of the local landscape and history. The man N.C. turned to (and later Andy and Andy’s artist son, Jamie) for that knowledge as well as dear friendship was Christian C. Sanderson, self-appointed local historian of the Brandywine River Valley and hoarder of all things historical. Chris passed away in 1966, but friends took his treasure trove and transformed it into today’s Christian C. Sanderson Museum. In addition to being a repository of some of the oddest and most touching artifacts of American history, the Sanderson Museum might just be the one and only place to see the “real” Wyeths—America’s greatest art dynasty.

Born 1882, Chris Sanderson always found himself drawn to American history—a life-long love affair heartily approved by his devoted mother. Although he worked as a teacher and later as a principal, history wasn’t just his job—it was his life. Chris hoarded before hoarding was cool, or at least on cable. From Teddy Roosevelt’s inauguration in 1904 through Lyndon Johnson’s in 1964, Chris attended the swearing in of every president for six decades, often with students and like-minded history lovers in tow. In addition to attending and collecting keepsakes from events such as inaugurations and the 50th, 75th, and 100th anniversaries of The Battle of Gettysburg, Chris saved what is literally the detritus of the American dream, such as the wood shavings from a floor upon which Billy Sunday once evangelized. Autographs of the famous and infamous lay on scraps of paper throughout Sanderson’s home. Teacher, historian, amateur musician, and even radio personality—Chris Sanderson cast a larger-than-life shadow over the valley he knew and loved so well.

When Sanderson died in 1966, his friend Tom Thompson accepted the monumental task of organizing and preserving the collection for future generations. “It took an enormous effort and the dedication of a true friend to sort through the rooms and hallways literally crammed from floor to ceiling with items, many of which were difficult to decipher and value due to their state of repair,” Gene Pisasale writes in The Christian Sanderson Museum—Tom Thompson Remembers. Thompson estimates that “roughly 60%” of the items in the house were beyond salvaging, making you wonder what wonders were lost to the incinerator. It’s a truly amazing collection of Americana—from the Revolutionary War and Civil War cannonballs lining the floor of the “Battlefield Room” to poignant relics such as a section of a bandage used to staunch Abraham Lincoln’s fatal head wound and the purse of Jenny Wade, the only civilian killed in the Battle of Gettysburg. Chris obtained that purse from Wade’s sister while attending the 50th anniversary of the conflict. Items like that purse—so heavy with the weight of history as well as of humanity—demonstrate just how powerfully the Sanderson collection is a history of the heart.

I visited the Sanderson Museum fresh from touring the recently opened Andrew Wyeth Studio (which I wrote about here). After seeing Wyeth’s world from the inside, I was hungry for more, so the Sanderson Museum was the perfect accompaniment. In fact, I think I learned more about the Wyeths at the Sanderson than in Andy’s long-time studio. The Wyeth and Sanderson families almost merged into one family over the years. They would celebrate holidays together. N.C. Wyeth would give Chris Sanderson’s mother copies of the latest work he had illustrated. When N.C. learned that Chris struggled with rent payments, he stepped in and helped (a tradition that Andy continued after N.C.’s death in 1945). Chris took candid photos of the Wyeth family at Christmas and other occasions. To my knowledge, many of these photos remain unpublished and can only be seen in the museum. When you see family images at the Andrew Wyeth Studio, they’re actually courtesy of the Sanderson Museum. In many ways, the Wyeths outsourced the documentation of their lives to their favorite historian.

In exchange for Sanderson’s historical expertise, the Wyeths gave Chris many gifts from their artistic gifts. N.C. gave Chris’ mother a painting of a Civil War scene. Andy gave Chris a watercolor of Independence Hall and a painting of Elfreth’s Alley, one of the oldest city streets in the United States. Chris clearly inspired Andy to explore his interest in history through his art. Andy painted a classically symbolic portrait of Chris that hangs on the first floor of the museum. A preliminary version of a later portrait by Andy of Chris, titled The Country Schoolmaster, also hangs in the museum as a sign of the warmth and humor in their relationship. A pastel of a landscape by Andy, the only pastel I’ve ever seen by the artist, signifies for me that Andy could experiment and be vulnerable around Sanderson, who helped fill the father-figure void after N.C.’s death.

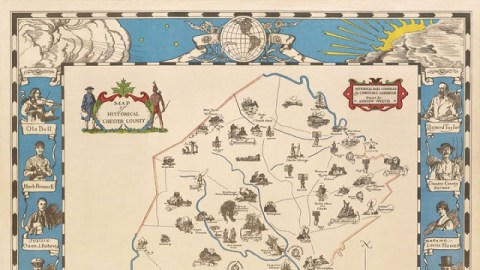

Perhaps the most significant collaboration between Chris and Andy was a Map of Historical Chester County (detail shown above). In 1937, the 20-year-old artist and 55-year-old historian created a map of the local region with as much of the local history and historical personalities packed into it as possible. Chris nominated figures with local connections ranging from Pennsylvania founder William Penn to Wild West showman Buffalo Bill to local boy turned baseball hero Herb Pennock, all of whom Andy made portraits of. The original pencil sketches appear in the museum, which also has prints from the original 1937 run of 5,750 available for sale. Seeing this collaboration opened a whole new dimension for me in regards to seeing Andrew Wyeth as a young man still looking for a direction to take.

Perhaps the greatest source of charm felt while walking through the rooms of the Christian C. Sanderson Museum comes from its intimacy, its macro-history given on a microscopic scale, but most of all its personality—the still-living personality of Chris Sanderson. That personality attracted nearly everyone who came into his orbit, including three generations of the Wyeth family. The quirkiness of the collection (which includes a vial of melted snow from the South Pole) matches perfectly not just that of Sanderson himself, but also that of the Wyeths. Sanderson melted any reservations the Wyeths had a formed a unique bond with them and their art. Anyone wanting to know the Wyeths needs to know the Christian C. Sanderson Museum and Chris himself.

[Many thanks to the Christian C. Sanderson Museum for providing me with the image above, press materials, and a review copy of The Christian Sanderson Museum—Tom Thompson Remembers by Gene Pisasale.]

[Image:Andrew Wyeth (illustrator) and Christian C. Sanderson (compiler). Map of Historical Chester County (detail), 1937. One of 5,750 printed by Beck Engraving Company, Philadelphia, PA. Original pencil drawing hangs in Christian C. Sanderson Museum. Actual prints from the original 1937 set available for sale from the museum.]