What’s the Big Idea?

When (if ever) is violence necessary? What (if anything) does it have to do with “manhood”? And what toll does a life of violence take on the human spirit?

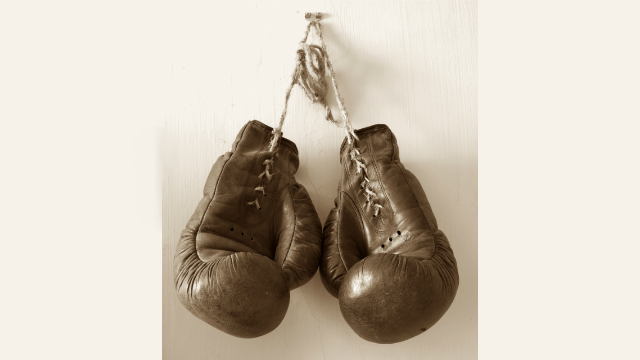

These questions writhe at the heart of Andre Dubus III’s profound new memoir, Townie. Forced at the age of 11 into the role of “man of the family,” Dubus became a fighter to defend his mother and siblings from predatory thugs in their poverty-stricken town of Lowell, Massachusetts. Now an accomplished novelist (House of Sand and Fog, The Garden of Last Days), Dubus reflects on the complicated nature of violence, and what exactly it does to the lives of those it touches.

Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) is one of those films that sticks with you. In you, maybe. Hard to shake the pathetic figure of David (played by Dustin Hoffman), a timid mathematician forced (and initially, significantly unable) to defend his wife against a hungry pack of less “civilized” men. Almost more disturbing than the violence itself is the nagging sense (which Peckinpah wants us to feel) that there’s some crucial force of manhood lacking in the “modern male” Hoffman represents – that, to paraphrase Hamlet out of context, conscience has made cowards of us all.

Coward or hero, Hoffman’s character is outnumbered. Even Charles Bronson wouldn’t stand a chance against them odds. But what’s at issue is something subtler: an internal readiness or reticence to do violence when necessary. Peckinpah wants us to believe that the readiness to do violence has something essential to do with “being a man.”

What’s the Significance?

Let’s take gender out of the equation for a moment. This is the classic Kid on the Playground Dilemma. Every middle class parent knows that fighting’s against the rules – not only of the school, but of civilized society. But there’s something deeply unsatisfying about teaching your child to run from the bully and go tell the teacher.

But this acculturated taboo against fistfighting has a rational foundation – the collective memory of how, in most instances, violence begets violence. How it kicks off a cycle which, once initiated, is hard to stop. And that it tends, ultimately, to destroy its practitioners and plenty of innocent civilians, too.

This brings us to Townie, Andre Dubus III’s new memoir – a profound meditation on violence that only he could have written. Dubus, the acclaimed author of House of Sand and Fog, does not fit the stereotype of a sensitive novelist (lean, haunted, bespectacled). Nor is he a swaggering brawler like Hemingway or Norman Mailer. But Dubus has known violence intimately – mastered it, you might say – and lived to write about it .

When Dubus was almost twelve, his parents divorced, leaving him, his overworked mother and his three siblings living in poverty in Lowell Massachusetts, a drug-ridden “town where the factory got closed down.” In order to defend himself and his family from predatory thugs, Dubus “got big” at the gym and learned to fight. He became a kind of self-appointed defender of the underdog – an avenging angel of the streets. But violence took a profound emotional toll on Dubus, and might very well have killed him, too, if he hadn’t decided to plunge his considerable energies into writing instead. In Townie, he attempts to untangle the intricate knots of his complicated past – and to decode the violence that gave birth to the man he is today.

Follow Jason Gots (@jgots) on Twitter