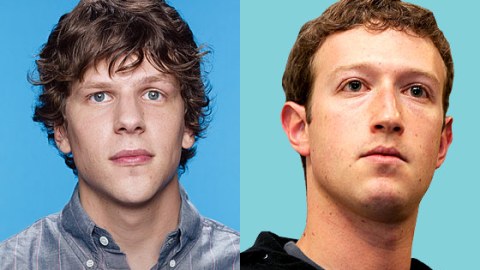

Aaron Sorkin: Social Network Screenwriter “Not a Fan of the Internet”

In last week’s cover story at New York magazine on the forthcoming Facebook biopic “The Social Network,” the film’s screenwriter Aaron Sorkin offers his pessimism about the nature and impact of the internet.

Here’s how NYMag’s Mark Harris describe’s Sorkin’s outlook:

“I’m going to give you a rant,” says Sorkin pleasantly. We’re sitting in the Terrace Room of the Sunset Tower Hotel in Los Angeles. Sorkin, a tan and dapper 49, looks so at home in these echt-showbiz environs (he’s even played a particularly acrid version of himself on HBO’s Entourage) that at first it’s hard to believe him when he says he still feels like a Hollywood outsider, more an East Coaster than an Angeleno, more a playwright than a player. But as he talks, it becomes clear that his sense of himself as an observer in a strange land fuels his writing and his thinking. He opens an elegant cigarette case, ignites, and prepares for liftoff. Soon enough, we’re up, up, and away in what proves to be a very well-designed hot-air balloon. The theme of this particular ride is going to be “I am not a fan of the Internet.” “Not a fan” is not a euphemism for “I’m ambivalent”—it’s a euphemism for “I hate it.”

Within seconds, we’re gusting across the entire cultural and sociopolitical landscape. It’s not hard to figure out that some of Sorkin’s animus is professional—in a way, The Social Network can be seen as a well-aimed spitball thrown at new media by old media—and some is personal. His 2001 drug bust for possession of mushrooms, pot, and cocaine is still eminently Googleable and a reminder that, as Zuckerberg’s furious ex-girlfriend tells him in the movie, everything on the Internet is written in ink. And his last series, Studio 60, was so completely and brutally dissected, episode by episode, on various blogs that, he says, “papers would take to quoting posts [from] a website devoting to not liking” the show. But his ingratiating high-gloss soliloquy has little sense of injury: While digressive, it’s always coherent, and while impassioned, it’s usually cheerful. He’s propelled by exploration and curiosity, not by rage.

As he revs up, we coast over the statistic that one in four Americans still believes Barack Obama was not born in the United States (“There’s just too much bad information getting out there, and I have to believe that’s mostly the fault of the Internet, which isn’t held to any standards of accuracy”). He points toward his unfulfillable vision of a web governed by libel and slander laws and held to old-fashioned standards of factuality (“People say, well, there’s so much Internet content, how could you possibly do that? And the answer is, there would be a lot less Internet content! Thinning out the herd is a good thing. There would be a Darwinian falloff of people who think they can go out and just state anything they want as fact”). He discusses his wavering First Amendment absolutism (“While everyone deserves a voice, not everyone deserves a microphone”) and his appetite to understand the right-wing talk-radio demagogues who hate everything that he, as a “liberal Hollywood elite,” stands for. He touches on anti-Mexican xenophobia, the bigotry that festers in the virulent swamp of unsigned chat boards, the Supreme Court justice who noted that the path to many of our freedoms is forged by basically bad people (“I think it was William O. Douglas, but I’m not sure, so can we stipulate that I don’t know who it was?”), Larry Flynt, CNN’s Rick Sanchez, why we watch American Idol, the dumbing-down effects of anonymity (“Anyone who has ever been in the stands at a Giants game understands that”), his occasional propensity to answer his Internet critics using his own name, his desire for a level of discourse that does not degenerate into “calling somebody a douche bag,” and the lack of a need for instant news.

“I have to tell you,” he says, “I don’t feel like I had any trouble getting information before. Every morning two newspapers were literally thrown at my house. All I had to do was open the door and get them. Anyway,” he says, sighing and finally, gracefully touching down, “I’m not quite getting the Internet.”