A Legend in His Own Mind: Gauguin’s Myth Making

After spending some tumultuous time together at the infamous “Yellow House” in Arles, Vincent van Gogh, no stranger to psychiatric help, thought that fellow artist and former roommate Paul Gauguin could use a professional, too. Taking Vincent at his word, modern art’s original odd couple thus seem more alike than different in the fragmentation of their personalities. Gauguin: Maker of Myth, the catalog to the exhibition running at the Tate Modern in London, England, through January 16, 2011 before moving on to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, from February 27 through June 5, 2011, picks up the pieces of what seems to be Gauguin’s shattered psyche and reveals the method behind his madness. Both a deliberate and an accidental mythmaker, Gauguin first became a legend in his own mind before he could become a legend in his own time, or ours.

“In choreographing his career, Gauguin mythologised his role as creator,” Belinda Thomson, editor of the catalog and curator of the exhibition, writes. “This self-promotional urge is seen here as central to his making of art, and not, as has been the tendency in the past, as an incidental biographical factor, an irrelevance or an embarrassment.” As part of the post-Courbet generation, Gauguin witnessed from afar the original artist-showman par excellence who proudly declared himself “The most arrogant man in France.” Gauguin’s similar lack of shyness helped catapult him to the top tier of post-Impressionists rather than emerged as an aftereffect. This approach to Gauguin “set[s] Gauguin’s oeuvre in the context of his increasingly fast-paced, globalised colonial world, his particular pursuit of cross-cultural exchange being unthinkable at any earlier time,” Thomson continues. This isn’t your grandfather’s Gauguin. In Gauguin: Maker of Myth, a Gauguin appears we can easily imagine comfortably rubbing elbows with contemporary uber-self-promotional, self-mythmaking artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst. Actually, I can imagine elbow rubbing quickly turning into elbow throwing in that crowd, as the massive egos vie for alpha supremacy. It’s this reenergizing of Gauguin, in all his brusque arrogance and hunger for attention, that makes his so human in a 21st century way.

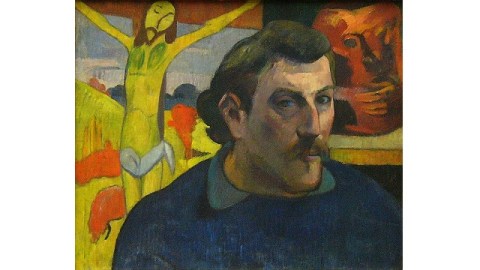

Gauguin: Maker of Myth gets under the skin of the artist and his art to show the hungry heart beneath. A painting such as Self-Portrait with Yellow Christ (shown above, from 1889-1890) captures the audacity of Gauguin not only placing himself on par with the messiah but also shamelessly plugging his painting The Yellow Christ in one breathless image. Gauguin carefully managed the tension between shamelessly overt publicity and the sense of primitive-drenched mystery in which he surrounded his persona. (Princeton University Art Museum’s smaller, more-targeted exhibition, Gauguin’s Paradise Remembered: The Noa Noa Prints [which I reviewed here], touched earlier upon this balancing act of the “open secret” of Polynesian ways presented in Gauguin’s art and writings.) “[A]lthough he certainly hoped that his writing would help to publicise his work,” Linda Goddard explains in her catalog essay, “for Gauguin to have offered literal interpretations would have thwarted his desire to emulate the ‘mystery’ of Polynesian culture, and risked reverting to the rational explanations of the civilized art critic.” Perhaps Gauguin’s eluding of the rationalist art critic’s “civilized” take has stood in the way of seeing the reasoning behind Gauguin’s very calculated mystery of self.

But, as the catalog explains, Gauguin wasn’t alone in plumbing the depths of the Polynesian mystery. “The here and there, the real and the imaginary, the mundane and the mythical, the civilized and the savage… permeable and changeable,” Vincent Gille lists in his essay, “the categories through which Gauguin weaved his way were more present than ever in the spirit of the times.” Orientalism in multiple forms swept across late 19th century France, reaching every corner of culture. Charles Forsdick’s essay on French ethnographer Victor Segalen, a near-contemporary of Gauguin also interested in Polynesian culture, demonstrates how Gauguin not only followed the trend of Orientalism but also made a significant contribution that transcended the myth he wove from his Tahitian material. Amy Dickson’s essay on Gauguin’s “very British reception,” beginning with Roger Fry’s groundbreaking 1910 London exhibition of Post-Impressionists and peaking with W. Somerset Maugham’s novel The Moon and Sixpence, proves how the Gauguin mythmaking machine hummed along even posthumously.

With 200 beautiful reproductions of Gauguin’s paintings, graphic works, ceramics, woodcarvings, and even manuscripts, Gauguin: Maker of Myth provides more than enough visual evidence of the mythmaking machine the essays explore. “Gauguin was a lover and reteller of tall stories who ended up believing, and finding creative nourishment, in his own narrative,” Thomson explains. In the end, Gauguin convinced even himself of the “Gauguin” he had created and drew strength from that creation. Looking upon Gauguin’s works in this exhibition, we can see how the persona Gauguin carefully crafted stands at the center of his oeuvre. Gauguin: Maker of Myth puts Gauguin the man who became a myth even in his own mind back in his proper place for his era and ours.

[Image: Paul Gauguin. Self-Portrait with Yellow Christ, 1889-1890.]

[Many thanks to Princeton University Press for providing me with a review copy of Gauguin: Maker of Myth, the catalog to the exhibition running at the Tate Modern in London, England, through January 16, 2011 before moving on to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, from February 27 through June 5, 2011.]