Darkness and Cherry Pie: David Lynch’s Map of Twin Peaks

Where is Twin Peaks? The fictional town at the centre of the eponymous, early-Nineties TV series – to return in 2017 as a miniseries on Showtime – isn’t too hard to pinpoint. The climate is rainy, the timber is abundant, and the coffee is religiously obsessed over. Surely, this can only be the Pacific Northwest.

Twin Peaks was indeed shot less than an hour’s drive east of Seattle, in a picturesque slice of Washington state, around the towns of Snoqualmie and North Bend to be precise. The jagged profile of Mount Si, looming over the area, suggested the twin peaks that provided the town and the series with its name (1).

Ultimately, however, the series’ exact location is incidental, even obstructive to its narrative. Stories that require the suspension of disbelief benefit from a suitably vague, or entirely fictional setting (2). The same applies to morality tales, which are most effective when set in some kind of Anytown, a location average enough to signify: It could happen here (3).

As a fine balancing act between supernatural horror and small-town soap opera, Twin Peaks falls well within both categories. So when asked to reveal in which state of the Union the town was located, series creator David Lynch coyly – but understandably – sidestepped: Twin Peaks was in “a state of confusion.”

Lynch is fascinated by that confusion. His cinematic œuvre is a balancing act between darkness and light, ranging from the unsettling surrealism of Eraserhead to the heartwarming ordinariness of The Straight Story. When stuffed into a single movie, that balancing act becomes the tension arc, as in Blue Velvet, where petty bourgeois aspirations collide with the excitement and danger of a dark, vicious counterculture.

That tension is given a supernatural gloss in Twin Peaks, as the murder of Laura Palmer, the local homecoming queen with a dark side of her own, lures FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper deeper and deeper into a netherworld of evil deeds and evil spirits.

True to its toponym (surely not chosen randomly), Twin Peaks is a double landscape, simultaneously an all-American small town (with all the homely values and home-made cherry pie you can stomach) and the hunting grounds of an unnamed, age-old, bone-chilling evil.

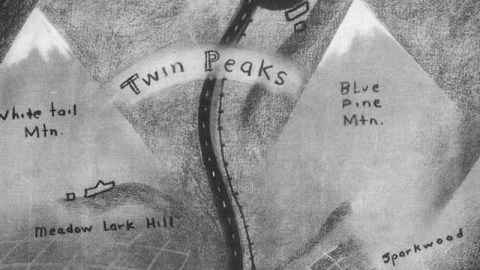

That duplicitous terrain was captured in a map drawn by David Lynch himself, meant to set the scene for ABC executives about to see the series’ pilot episode. As a type, this map is indebted to the adventure book endpaper map (4) and, more generally, to any hand-drawn itinerary: it sacrifices accuracy for detail, enhancing the elements of the landscape that are relevant to the story.

The map of Twin Peaks opposes the regular grid of human settlement to the jagged terrain that envelops it. The monochromatic colour scheme enhances the sense of dread. Instead of the variety of greens, browns and blues used in most topographic maps, Lynch opted for a narrow range of ominous greys, black for roads and lakes, and smidgeons of white for the snow-capped peaks joined by the banner carrying the town’s name (5).

Some of the names are familiar. There’s Ghostwood, a National Forest and famously home to a protected species, the majestic Pine Weasel. An almost similar name is referenced as “Sparkwood and 21”, the intersection where Laura jumps off James Hurley’s bike and runs into the woods. There’s the US-Canada border, across which lie the illicit pleasures of One-Eyed Jack’s. And there are the Pearl Lakes, where the Palmer family used to vacation in summer.

Other toponyms are unfamiliar: Black Lake, Meadow Lark Hill, the Lower Town and the Flats did not figure prominently in the series. Nor did the “Lucky Hiway”, prominently passing through town (6).

Well, maybe not their names, but their layout, the fact that they were on the map, was important to Twin Peaks. David Lynch’s map was more than a mere mood-setter for studio execs. It was an essential tool for writing the series, as he himself once admitted: “We knew where everything was, and [the map] helped us decide what mood each place had, and what could happen there. Then the characters just introduced themselves to us and walked into the story.”

And then the tale – to quote Tolkien – grew in the telling. That’s what it looks like at least from another map of Twin Peaks, briefly glimpsed in the second season on a blackboard in sheriff Truman’s office. The basic patterns of settlement and terrain refer back to Lynch’s pre-pilot map, but are much more elaborate (7).

One last thing about pinpointing Twin Peaks. On the earlier map, the “Lucky Hiway” is numbered 21, which fits with Washington State Route 21. That 191-mile road extends from Kahlotus, in Washington’s south-eastern corner, in a semi-straight way up to Danville, on the Canadian border. So does this provide Twin Peaks with at least a ‘corridor’ of potential locability?

It seems Mr Lynch has taken great care to maintain Twin Peaks’ “state of confusion”, for not only is this corridor located over 150 miles east of the actual filming locations, it is also situated about 60 miles west of FBI agent Dale Cooper’s own rather precise diary dictation at the start of the pilot:

“Diane, 11:30am, February 24th. Entering the town of Twin Peaks. Five miles south of the Canadian border, twelve miles west of the state line.”

Maybe the ultimate message is: wherever it is, Twin Peaks is closer to home than you think…

Mr Lynch’s map found here on Austin Kleon’s blog on writing and drawing. The blackboard map found here on twinpeaks, a Twin Peaks mailing list at Yahoo! Groups.

Strange Maps #507

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

———-

(1) there is a Little Si right next to (Big) Si, but this is little more than a hill.

(2) Superman’s heroics work well in Metropolis, Batman is at home in Gotham; either would seem out of place in New York, the real city both fictional ones are (loosely) based upon.

(3) Moralising via abstraction is an ancient technique, see also the medieval morality play Everyman, the obvious implication of which is: It could happen to me.

(4) The grandaddy of which is the Map of Treasure Island (see #378). For more recent examples, see #157 and #456.

(5) To my knowledge, the topography of the twin peaks is never discussed in the series, so it’s really fascinating to see them named here, as White Tail and Blue Pine Mountains.

(6) Truly a ‘Lost Highway’.

(7) According to some hardcore Twin Peaks fans, the map contains the images of two dogs. I only see one, to the left of the main north-south artery.