Is it Finally Time to Take Pop Art Seriously?

How can you take soup cans seriously? Is it possible to make high art out of low brow bits from comic books? Critics and even fans of Pop Art have laughed at the genre even as they paid homage to it. When Jonathan Jones of The Guardian recently surveyed the state of today’s art as the spawn of Pop, he asked, “Is art a profound cultural enterprise, or just a very expensive way for the rich to avoid thinking?” In The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha, Hal Foster tries to bring thinking back to Pop Art by arguing that it began with thinking—specifically, the same kind of thinking that could save art today. For Foster, Pop Art isn’t about the soup cans. Instead, Pop is about affirming painting at the same time it challenges painting to remain relevant to today’s world.

Foster sees Pop Art “saving” painting in its first incarnation. Just as “mass culture” and even “avant-garde art” threatened to leave painting in their wake, Forster writes, “painting returned, in the most impressive examples of Pop, almost as a meta-art, able to assimilate some media effects and to reflect on others precisely because of its relative distance from them.” When everyone else focused on content, the Pop Artists focused on form. “[C]ritics failed [Pop Artists], for if they regarded the content of Pop as obvious,” Foster believes, “they dismissed its from as facile.” This failure to see the real purpose of Pop continues today, a mistake that Foster hopes to correct in this new history, which focuses on Pop painting exclusively. Foster’s laser beam focus on painting forces him to exclude sculpture (and thus pass over Claes Oldenburg and others) and to exclude women and minorities in favor of a white, male-dominated pantheon of Pop painters already familiar to a mainstream audience. Freely admitting these limitations, Foster still sets out to give a history—not the history—of Pop Art as the only logical response of painting to media-dominated modern life.

Who does Foster decide to write about when he writes about Pop? Warhol, of course, and Lichtenstein, but before even them he goes back to Richard Hamilton, the founding father of the movement, if such a loosely affiliated, multinational band can be called a movement. Ed Ruscha and Gerhard Richter bring up the rear in this race, with Richter perhaps being a puzzling or an inspired choice, or both. But Richter, celebrating his 80th birthday and six decades of painting this year, says so much about modern painting in his work that any discussion of art seems missing something without him somewhere in the mix.

According to the art history books, Hamilton started Pop with his 1956 collage titled, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? Launching from that point of origin, Foster easily moves forward through all of Hamilton’s oeuvre while simultaneously peering back at the Surrealist and Duchampian roots of the work. What fascinates Foster about Hamilton is his ability, while “steeped in both popular culture and high art,… to rehearse, indeed to test, the signal operations of each; at once reverential and cynical, he seeks to explore, indeed to exploit, the changed relationship, the charged overlap, between the two.” Although that “charged overlap” momentarily electrocutes painting, Hamilton demonstrates the “decay” of the rotting corpse of painting “within painting, for only there is it fully articulate,” Foster continues. Following the “fine tradition of [painting’s] popular decrepitude” that traces back to Manet, Hamilton saves painting by showing how it was dying.

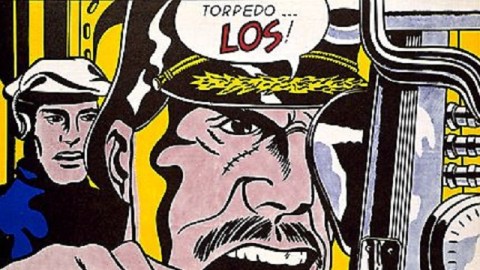

Similarly, Roy Lichtenstein saves painting by changing the rules of the critical game. Using “low sources” such as bits of comic books (for example, Torpedo Los, shown above), Lichtenstein maintained his “lofty goals” of form, pictorial unity, and dramatic focus—“old school” values updated for the Pop age. Where others saw reproduction as “an existential dilemma,” Foster explains, Lichtenstein saw merely “a historical problematic” to overcome. “At the very least,” Foster concludes, Lichtenstein “helps free us from two automatic habits: obeisance to high art on the one hand, and obedience to mass culture on the other.” Just when you float one extreme as the ideal to follow, Lichtenstein the cultural submariner torpedoes it in the name of balance and intellectual honesty.

In Foster’s hands, Ed Ruscha emerges as a modern art Buster Keaton—king of the deadpan: “funny, desolate, both.” When Ruscha paints Standard Station, which depicts the actual brand name of a standard gas station chain, his “redoublings of word and image… render meaning less stable, not more.” Instead of standardizing standardness, Ruscha makes you rethink the whole standing idea of standardized anything, leaving you with no standards to stand on. When Ruscha moves on to his silhouette paintings in the 1990s, you “sense not ‘a shining city on a hill’ [per Reagan], but the twilight of the American gods,” Foster writes in one of his most eloquent (of many fascinating and memorable) close readings of these artists. By the 1990s, Ruscha suggests, even the old standards, however false or true they may be, are fading with the last light of the glory days of the American dream.

Where Ruscha silhouettes imagery, Richter blurs, which Foster calls “the most evasive of his actions”—no small claim for an artist that evades the photographic as he dances dangerously around it. “[A]t once immediate and meditated, traumatic and protective, piercing and blasé,” Richter’s blur delivers the “charge” (an electric and always heavily loaded word in Foster’s book) that reminds the viewer where painting can go that photography cannot. Foster opens the chapter with a quote by Richter calling Warhol “not so much an artist as a symptom of a cultural situation,” which is an odd starting place to make connections, but Foster uses Richter’s resistance to labels and iconoclasm to connect his techniques to the Pop art challenge-affirmation dual dynamic that unifies The First Pop Age.

Foster truly excels when he takes on Warhol, who sits at the center of all things Pop like a bewigged Satan at the frosty center of Dante’s Hell, with all things Pop eventually feeding down to him. Where others stress Warhol’s exuberance, Foster focuses on Warhol’s love of death and decay, beginning with the Death and Disaster series and continuing on to the torn labels of the seemingly innocent soup cans. Death extends even to a death of the self in Warhol’s film series of Screen Tests. “Can anyone—sitter or viewer—be said to pass his screen tests?” Foster asks. If you’ve ever subjected yourself to the tedium of watching one of Warhol’s “Superstars” awkwardly fidget before the camera and found yourself fidgeting, too, Foster suggests that our shared realization of the construction of identity (and it’s too easily revealed deconstruction) is the culprit. Foster’s analysis of Warhol’s “distressed” image—most famously in the worn out icons of Marilyn and Elvis—will distress you emotionally, but leave you with a greater intellectual appreciation of Andy.

Foster admits he “played down [Pop’s] sheer delight in popular culture,” for the sake of having it finally taken seriously. In many ways, The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha is Foster giving the art history world a “Come to Jesus” talk, not necessarily with Warhol playing the title role, although he would have liked that. For Foster, “[t]he politics in Pop [are] pitched differently, centered on its commitment to what is held in common, including our shared image world understood (perhaps perversely) as a newfangled commons.” While many politicians today employ “dog whistles” in their politics to reach the darkest, most divisive aspects of our souls, Pop Art sounded a clear, albeit oddly tuned call for people to turn to art (in this case, painting) to find what unites us, for good or ill. Hal Foster’s The First Pop Age makes the Pop Artists of years gone by seem not only much more serious than ever, but also much more seriously relevant to our image-confused modern consciousness than ever.

[Image:Roy Lichtenstein. Torpedo Los, 1963.]

[Many thanks to Princeton University Press for providing me with a review copy of The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha by Hal Foster.]