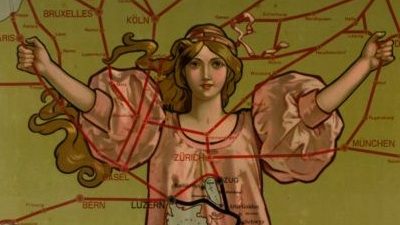

566 – Gotthard Girl’s Pioneering Intestine

An angelic lady from the pre-raphaelite school of femmes fatales is stretched across a map of Europe. Her raised hands clutch a sketch of the late-19th-century European rail network at two of its budding nodes: Paris and Dresden. The lady’s feet and dress are spilling into Italy. The clue to the significance of the allegorical woman’s position is in her Swiss torso – to be more precise, in the black line that meanders across her body, north to south.

That curly intestine represents the Gotthardbahn, the railway that was the first to connect the rail networks of Germany and Italy. This connection, established in the last quarter of the 19th century, overcame an age-old physical barrier.

Ever since humans had populated and traversed Europe, they’d been confronted with the geographic fact of the Alps [1], separating the Italian peninsula from western Europe’s north. Traffic across the mountains was often arduous, sometimes lethal. Cue Hannibal’s elephantine army, struggling across an unknown mountain pass [2] from Gaul into Italy in the 3rd century BC.

Rewind a few millennia to the death of Ötzi. The now-famous ‘Snowman’ – Europe’s oldest mummy – was found in 1991 near an alpine pass on the border between Austria and Italy. That’s where he may have been caught out by a snowstorm while trying to cross the mountains [3], 5300 years ago.

In more recent centuries, hardy tradesmen and the fledgling postal service struggled across the alpine passes. The advent of rail technology, at around the first third of the 19th century, promised a radical improvement.

Determined not to let the Austrians become the only gateway between Germany and Italy via the Brenner Pass, the Swiss decided to cut a railway through the Alps. A debate raged on whether the enterprise should be financed by the national government or by private initiative [4]. For a quite a while in the mid-19th century, the issue overshadowed all others in Swiss politics, dividing public opinion into two camps as sharply as once religion once had or ideology later would.

Private enterprise eventually won the day, but the German and Italian goverments, plus those of the Swiss cantons affected by the railway line, would participate in the Gotthardbahn-Gesellschaft, founded in 1871 in Lucerne to build and exploit the line, which was to run just over 200 km from near Lucerne to Chiasso on the Italian border.

The first stretches were opened in 1874; but these were in the easily accessible lowlands. Crucial to the rail link was a 15-km-long, double-track, single-tube tunnel, dug in the mountains between 1872 and 1881: the actual Gotthard Rail Tunnel [5], connecting the central Swiss canton of Uri with the traditionally remote canton of Ticino.

When it was inaugurated – exactly 130 years ago this month, from 21 to 25 May 1882 – the Gotthardbahn crossed 1234 stone and iron bridges [6]. It was a pioneering achievement, solving the seasonal isolation of several alpine communities, and eventually did fulfil its promise to connect the German and Italian rail networks.

In 1907, the Gotthardbahn was integrated into the Swiss federal rail system. In 1922, it was electrified. Its strategic importance was underscored by the Swiss army forts constructed along its course.

Still known as the Gotthardbahn, its spectacular route leads past some of Switzerland’s great lakes [7], and through the Alps, executing a few spirals to gain altitude.

Over the decades, the Gotthardbahn has hosted some of Europe’s most iconic rail services, including the Trans Europ Express (TEE) and the Rote Pfeil (‘Red Arrow’). At its southern terminus in Chiasso [8], the site of a large switching yard, most trains change locomotives, due to different traction voltages in Italy.

The Gotthard Girl on this poster, one of a series of promotional artworks from the early years of the 20th century, underlined the unifying quality of the Gotthardbahn: great northern cities like Paris and Dresden were within the grasp of modern train travellers, and the cities of northern Italy lay at their feet.

Allegorical females are nothing new in cartography – in fact, on many of the early world maps, each corner would be embellished by a female personification of the four continents then acknowledged: Europa, America, Asia and Africa, each with the appropriate animal and vegetal attributes.

These allegories soon invaded the map itself – see #141 for an image of the continent of Europe fashioned in the form of an allegorical queen. Much closer to Gotthard Girl are allegories celebrating modern achievements, personified by allegorical persons, like the two women sharing a Panama kiss (#188) or the dissected body showing Superior, Wisconsin to be the heart of the American Man of Commerce (#374).

Many thanks to Thomas Bachmann for sending in this map, found here at Un Deux Trois Galerie.

___________

[1] It’s no coincidence that that Alps so completely shield Italy’s north: they are the result of plate tectonics, more precisely of a northward collision of the Adriatic plate, bearing the Italian land mass, with the southern flank of the Eurasian plate.

[2] No reports survive of Hannibal’s trajectory across the Alps; military historians have proposed several possibilities, including the Col de Clapier, the Col de Montgenèvre, the Col de Mont Cenis, even the Col du Petit Saint-Bernard.

[3] It has also been suggested that he was accidentally killed, or purposely sacrificed.

[4] Not entirely unlike current debates in various countries about the financing of high-speed rail.

[5] The longest rail tunnel in the world at the time of its construction.

[6] Stone was used for bridges up to a width of 12 metres, iron for all others.

[7] Past Lakes Zug, Lauerz, and Lucerne (in German: Vierwaldstättersee, or ‘Lake of the Four Forested Cantons’), and across Lake Lugano, via the dam of Melide (constructed in 1848).

[8] Not far from Campione d’Italia, an Italian exclave discussed in this episode of the Borderlines series.