Bloomberg Versus Giant Sodas: It’s Not the Nanny State, It’s Democracy At Work

Mayor Bloomberg’s latest anti-obesity proposal—ban sales of giant flagons of sugary drinks by next spring—has been criticized as bad politics in support of good policy. In fact, it is the opposite: Such a ban will do almost nothing to lower obesity, but it is an example of democracy working the way it should.

The plan won’t achieve much because it’s premised on the notion that the entire population drinks too much soda, and that this contributes to the general rise in obesity in the city’s population. As Trevor Butterworth nicely explained here, though, general statistics about per capita soda consumption disguise reality. Most people don’t consume vast amounts of sugar water. But those who do, well, they really do. Most of the population, then, won’t be affected by the regulation. And what’s to stop the other 20 percent from just buying two or even three cups at the new 16-ounce maximum size?

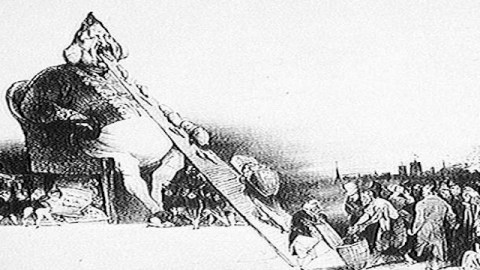

But Butterworth also castigates the Mayor for political tone-deafness, saying he has turned soda into “a symbol for intrusive, meddlesome, government.” In other words, the Mayor has set back the cause of health-promotion by linking it to the dreaded imagery of the Nanny State.

The assumption here is that there is some fixed boundary between private life and public affairs. In fact, this boundary moves over time, with changes in societal circumstances and scientific knowledge.

For example, in 1900, millions of people around the world were outraged at the thought that the government could force them take a vaccine for smallpox—what could be more private, and sacrosanct, than the individual’s right to control his own body? How could the government force anyone to offer herself up to “pollution and filth and disease“? Clergy preached that “medical liberty” was vital as freedom of religion. Doctors protested the trampling of their professional dignity. In Great Britain, anti-vaccinationists were strong enough in Parliament to win a personal-conscience exemption in the 1898 mandatory immunization law. It gave birth to a new legal term: “conscientious objector.”

But the germ theory of disease had laid bare an undeniable connection between the private life of the body and public welfare. When a forced-vaccination case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905, the libertarians lost, 7-2, as the Court held that individual rights are outweighed by the community’s “right to protect itself against an epidemic of disease which threatens the safety of its members.”

In other words, the turn of the last century saw a redrawing of the boundaries of private life, in the name of fighting infectious disease. Today, as the Bloomberg initiative illustrates, we’re arguing about whether to redraw those boundaries again, in the name of fighting chronic disease (diabetes, heart ailments, stroke, kidney failure and so on). The reason: Your likelihood of coming down with one of those appears to depend on small, habitual, daily choices about what you eat and do with yourself.

That’s the case for seeing these private choices as public business. Maybe the result of today’s ongoing political debates will be to leave the definitions of public and private life as they were in 1980. But I wouldn’t count on it.

In any event, the right thing for a democracy to do is to have the debate. This is my second problem with the “Nanny State” caricature. In announcing his ban, is mobilizing the angry public and attracting argument against it (and a few in favor). If he succeeds short-term (likely, as he needs only the approval of the Board of Health, which he appointed) then we, the sugary-drink-constrained hordes, might adapt to a new landscape, as we have with smoking in bars and restaurants. If we decide instead this ban was stupid, we will vote in a new Mayor sworn to oppose it, and/or get the City Council to overturn it. This is how it’s all supposed to work—debate, persuasion, votes, majority rule.

This noisy and messy process seems to me entirely preferable to the other game in town, which is to get people to change their behavior by insidious means. Set up the organ donation system so that people unthinkingly check “yes.” “Nudge” them to put more into their retirement IRAs by changing the forms a little. Tell them they should cut down on soda, even if, for many people, it isn’t true.

I’m referring here to the mentality embodied in this reaction to a recent study suggesting that regular exercise can be harmful to some healthy people: “There are a lot of people out there looking for any excuse not to exercise,” William Haskell, emeritus professor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center, told Gina Kolata. “This might be an excuse for them to say, ‘Oh, I must be one of those 10 percent.’ “

Think about that for a moment. Professor Haskell doesn’t dispute the merits of the research; he’s simply saddened that people will learn about it. Because people, pfffft, you never know what they’re going to go off and do with information.

I’ve seen a fair amount of this attitude toward fellow citizens, summed at one wellness-promotion conference a few years ago as “how we can minimize consumer irritability while extracting their cooperation in improving their health and wellness.” It is as undemocratic as you can get. Yet governments are increasingly interested in it.

So, two cheers for Bloomberg’s soda proposal. In a time when public-health officials are increasingly attracted to hidden, unnoticeable persuasion, at least he wants to play fair.