Empathy, Cruelty, and the Curated Life

Cruelty preoccupies me. I find that stories of cruelty stay with me, hauntingly, and infiltrate deeply. I cannot conceive of it in its most basic elements, the physical act of hurting another person. Unintentional psychic injuries against others are all too understandable to me, if not all but inevitable in a life that has other people in it. But the deliberate malice of cruelty eludes me.

Some new research finds compassion and empathy to be as intrinsic to human character as self-preservation. I hope that this is true, although it’s hard to discern in the headlines today. Then again, cruelty fascinates, so we hear about it. In contrast, goodness gives the profoundly deceptive impression of being transparent, unremarkable, and without charisma.

If empathy is hardwired, then it still seems to require some flexing and practice to unleash itself in the world.

Empathy, or at least non-cruelty, doubtless requires a capacity for perspective-taking. You develop empathy by being around people with different lives and beliefs who you are forced by circumstances, manners, or custom to tolerate and listen to—or at least not to blow up, shoot, rape, maim, or scream at, either in person or virtually.

You could also develop empathy by reading stories and books, any and all books, about anybody and any character or topic under the sun—anything that has a subject or character that you don’t already recognize, or know.

Presumably we develop empathic skills by listening to intelligent discourse among differences in the political sphere.

All of these modest empathy-building habits may constitute a more lasting anti-cruelty, anti-rape initiative than the well-lit path, or new laws against harassment. But they’re in conspicuous short supply in the social milieu of the day, and in the online worlds where much of social and intellectual life is migrating.

The normal pathways to empathy and identification—random encounters with the other, or situations where we must tolerate diverse perspectives and lives—are being replaced by ever more finely-sorted and niched worlds.

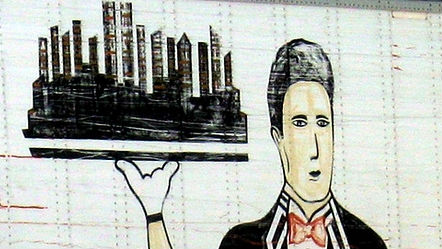

These worlds are curated for us by personal techno-butlers. The techno-butler sorts through, discards, selects, and displays items to read, wear, cook, drink, drive, use, believe, befriend, or like, as gleaned by our past behavior. They suggest that we like pages based on pre-existing, already-established preferences; that we buy books just like the ones we’ve just bought; that if we liked this dress, we’ll surely like this one, as well; that we stay on the track of our own political views, reiterated into eternity with like-minded comrades in social media’s echo chamber. Online habitats fortify our personal comfort zone. Through Amazon, you can buy books forever solely in the consumer “silo” of Scandinavian detective fiction, if you like. When you’re finished with one, a message, “If you liked this…” or “readers who bought this also bought…” will guide you with the white-gloved seamlessness of a perceptive, discreet manservant to books just like it.

Under the discerning curation of the techno-butler, matters of taste, creed, identity, and affiliation are decided based on already-established affinities.

You need never stray from the self that you think you are.

Of course, we can always seek out diverse points of view and useful irritants to our own beliefs. That’s what new technologies enable us to do much more easily. Someone in North Dakota can easily befriend hipsters in New York, in the privacy of her own home.

But we must seek out that diverse point of view. The default momentum with the curated life is toward homogeneity, not heterodoxy or heteroglossia. Existing biases of preference and belief are perpetuated. It’s one of the biggest surprise hypotheses of the Internet revolution that it might have encouraged belief balkanization and tribalism when theoretically it could have done the opposite.

We don’t read much. A Pew study found that Americans read a median of six books in a year. Half read less and half read more. When we do read, we read less about people and stories unrelated to our lives. Self-improvement, inspirational, and “self-centered” books, in the literal sense of books designed to speak to your particular problems, worries, or issues (how to be happier, more pious, or sexier) dominate the sales. Here, too, the empathy-building functions of reading and literacy defer to solipsism.

Rather than read about them, we shoot the other in lifelike single-shooter video games. While the shooter is a very real subject to himself, the others—the characters in the game—are there to be shot.

We don’t hear intelligent discourse of dissent in the public, political sphere much. This point is too painfully obvious to elaborate, to anyone who’s had to listen to a politician in the last decade, or read the rants of embattled, ideologically non-empathetic partisans online.

The solutions of perspective-taking and empathy-building through books or talk may seem remote from the rape of a 15-year old in Nova Scotia or California. But they’re not. Cruelty festers when empathy and perspective-taking fail—when it becomes easier to look at others at a remove, and as less than entirely real to us as fellow humans. Moments of cruelty and non-empathy are what it looks like when the social compact frays.