Things Aren’t What They Used to Be: Is Ownership Passé?

You spend a lot of time talking about sharing and alternatives to ownership when your child’s in preschool. In the morning story circle you don’t want to be an avaricious, cookie-hoarding Vanderbilt. It seems morally arbitrary, that we spend so much time instilling an ethic of sharing that we’ll soon allow to be weedily overgrown by other priorities. Children start kindergarten as communitarians, and leave high school as robber barons.

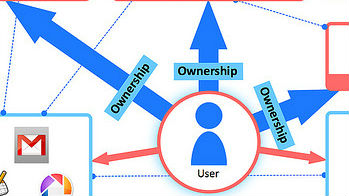

The “ownership society” prevailed over Communism in the Cold War. Nevertheless, sharing and alternatives to ownership are wandering in through the back door of history today—spontaneously, and renamed. Although it doesn’t have much (anything) to do with the overthrow of capitalism, alternatives to private ownership are undergoing an intellectual second virginity. It works this way sometimes: When an idea is declared dead historically, it’s free to be resurrected as a good idea.

The uber-luxury, uber-rich ski resort communities of Colorado are places that Marx would have been ashamed to visit and its residents would have been ashamed to host him. All the same, they’re places with improvised collectives, and an alternative to conventional ownership. They don’t call it a collective, of course. They call it “fractional ownership.” It’s ownership of one thing, shared by several. Unlike a rental or timeshare, the fractional owner of property, whether it be a sailboat (with a “fractional sail”), penthouse, ski lodge in Vail, or a luxury Paris apartment, does own a bit of the property. In this plush revolution of communalism, owners can sell their slice and bequeath it to their heirs. There are fractional developments throughout the world (250 in North America) as well as fractional ownerships of individual properties.

“Co-housing” is a similar hybrid of proprietary communalism. There are 90 co-housing communities in the U.S., and over 120 in planning and exploration. With co-housing, people own their own homes, but share some meals, resources, and decision-making with other members of the community and maintain public spaces.

It’s not a rejection of ownership, but ownership lite.

Urbanist Richard Florida astutely sees (home) ownership as out of step with the not so new economy. It might have made sense 60 years ago, when workers stayed put near the corporate office or factory where they could conceivably work for a lifetime. And, to be fair, home ownership still have a vague but compelling mystique. After my husband and I bought our first house, so many feelings and satisfactions conveyed in the word owner—solidity, stability, and adulthood. Mostly, ownership made it easier to imagine long-term, to move characters on and off the ever-fixed mise en scene of life that the house became. Maybe you need one fixed point of orientation in life, to manage the feat of long-term fantasy. When you’re a young renter, and all facets of your life are a mobile in complex motion, the intergenerational imagination is harder to conjure, or trust.

But that fantasy of ownership may be growing obsolete, or getting replaced with another. Florida endorses the rehabilitation of renting as a more compatible housing mode with the 21st-century economy. “Mobility and flexibility are key principles of the modern economy,” he writes. “Home ownership limits both.”

Houses are only the largest example of a subtle but pervasive revision of ownership. What we own today might be the milder, more figurative commodity of experiences rather than things.For example, vacation timeshares are a flourishing business, where you get access each year to a few weeks’ worth of a vacation home. Timeshare businesses speak of “Vacation Ownership.” You don’t own the place–you own the vacation. This preserves the prestige of ownership, but with an experience, not an object.

So does the “leased luxury goods” business in bags, jewelry and watches, which promises that “instead of owning an asset, you can just buy the experience.” Essentially, they envision object-less ownership. Jennifer Hyman is the CEO of Rent the Runway, which she thinks of as a community, not a business. It lets women rent high-end designer gowns. Rent the Runway gives “access” to “your dream closet,” thereby giving the client (not customer) a certain proprietary boast of having a virtual, private wardrobe at their disposal, even if the closet isn’t actually in their home, or actuallytheirs. Women can “experiment without the anxiety of investing.” Note that ownership has devolved in this description from a privilege to an anxiety.

Ownership might be getting replaced with membership, or revised to mean membership. In the not-distant future, maybe we’ll belong to dozens of “exchange communities” or bartering networks of varying levels of exclusivity. The largest barter network in the Maryland-DC area, Barter Systems Inc., has over 1400 members. Members can barter a mailing list management service for stress management or maid services.

William McDonough is a visionary leader in “eco-effective design.” He sees manufactured products that we own as “essentially, packaging for services,” and valuable for the service, not the object. “What if we thought of the auto industry not simply as a maker of cars but as a provider of mobility?” he brilliantly questions. As a “mobility provider,” rather than a car maker, a manufacturer might offer customers “access to many different kinds of cars, rather than selling them a car,” McDonough imagines. “Why own and maintain three cars when you could use the service of a big, spacious vehicle for family trips, a sports car for a weekend date, or a public community car to transport your children? In each case you’d be provided the service of mobility by an automaker that owned and reused the vehicles’ valuable materials and utilized them effectively…”

There’s something compellingly carefree and unencumbered—even luxurious?–about this vision. ZipCar and bike network members swipe a card, pick up their cars or bikes when needed, and then drop them off later. You’re not burdened with dipsticks or mechanical innards, insurance policies, fumbling for the cab fare, vulture-circling an imminent parking spot, or caught with half-eaten sandwiches in your car. Instead it’s like a British country estate, serviced by mechanics and chauffeurs who, like ZipCar, magically produce a vehicle. With membership and electronic billing, actual cash needn’t exchange hands. Under the circumstances, what would ownership actually add by way of prestige?

In the same vein, Netflix isn’t a video rental business but an entertainment provider service. Netflix intuited that the service it offered wasn’t the video as a tangible product but the experience. Netflix doesn’t provide discrete rentals of discrete videos for a discrete amount of time. Instead, for a membership fee, you get unlimited access to what you want, when you want it—and you’re liberated from the ungainly anchor of ownership.

Some of our most prized status objects today are technological. They’re valued for their timeliness, not their timelessness. The very newest, latest gadget is the most prized and sought. That’s in contrast to earlier decades, when the most prized possessions–an exceptional piece of furniture, jewelry, silver, or a fine leather bag–tended to appreciate in value.

The accelerated metabolism of obsolescence for our most prestige-laden gadgets seriously diminishes the appeal of ownership as well.

Why own, when we’ll get Blu-Rayed, eventually. The fragile images of my family’s life together, first seared onto Super-8 home movie film in the 1950s and 1960s, have since wandered almost nomadically, and at great expense, from the actual Super-8 to a VCR tape, from a VCR tape to a DVD, from transparent slides to digital images on my desktop. In a few years, the images will surely embark on a journey again to find temporary refuge on the new, new thing.

Open-source coding is the collective authorship and possession of computer code, the DNA of the digital age, in self-organized peer-to-peer communities. Open source codes such as Linux are not owned or proprietary. Any programmer can contribute, fix a bug, and share their programming solution with the community. It’s free, you don’t buy anything, and it’s always moving, changing, and evolving. It’s more like a perpetual draft of a thing, and therefore never a finished—ownable—product. Yale Law School professor and visionary Yochai Benkler coined the term “commons-based peer production” to describe collaborative, open-sourced coding. Benkler thinks in terms of “peer property,” not private ownership. Peer property licenses such as Creative Commons recognize individual authorship, but without exclusive property rights.

Commerce still happens. We do buy reproductions of music, books, movies and creative products in the digital economy, but we don’t often hold and possess them. When CDs were new and wondrous, a friend in graduate school took literally the hype that they were indestructible and that you could do anything to them.

“What’s this coaster?” I asked him one night as I set a beer down on it.

“That’s a CD,” he intoned, reverentially.

With iTunes, I buy a song and then own access to the experience of listening to it. I don’t really possess the music, as I could a CD that I cavalierly used as a coaster. Ownership no longer implies control at will, but access at will.

It’s not that we’ve not bought something, and it’s not that someone, somewhere, hasn’t made a profit. We have the soul and economy of commerce and capitalism withoutpossession.“Consumers want to enjoy products without owning them,” a 2010 Korean Times article observes. This points to the emergence of a new breed: a world of “owner-less consumers.”

We’re not entirely Matrix yet. Things—actual, tactile things—still do get made by industrial means of production, although increasingly not in the United States, as manufacturing migrates eastward. But even new ideas about the old industrial processes of manufacturing and design are beginning to revise the biography of a thing.

The most basic assumption we make about things we own is that they stay what they are. If you’re born a chair you die a chair. When we own a chair and tire of it, we “kill” it off, still as a chair, by throwing it out, selling it, or donating it. Things owned don’t change morphology and purpose.

Re-purposing and reinvention call into question even this prerequisite of possession. Like the open-source code that is never a finished product but always a draft, a thing that we make is plausibly never finished with its evolution. Re-purposing extends the biography of a thing beyond the time of our ownership (and, at the other end, the rehabilitative marketing ploy of “pre-owned” luxury goods backdates the biography to before our ownership). “Cradle to Cradle” certification sets new standards for manufacturing in eco-friendly, sustainable ways. The standards aspire to a zero waste manufacturing process where all elements, and the final goods, are used, re-used, and re-purposed, such that there is no “waste” in the process.

Cradle to Cradle evaluates among other criteria whether companies are designing products for “future life cycles,” and reincarnations. Do we still own a chair when it becomes a box in its repurposed future life? It would sound, and be, absurd to think so. The thing has metamorphosed into another, as if it has a soul that survives its corporeal forms, and so our ownership was incomplete, transient and conditional—something we had, for the time being, in one of the possession’s lives.