The Risk Factor of Loneliness

Ross Douthat, the only conservative columnist for the New York Times, reports some good news and some bad news.

The good: The Americans are becoming less criminal and less violent. There are fewer murders. And I’m adding or guessing that right as we become attuned to the dangers of bullying, there’s actually less frightening bullying. Not compared to Europe, of course, but to our own past, we live in a safer society, one driven less by hate and at least seemingly less by cruelty.

The bad: Americans—especially middle-aged men—are become more suicidal. That’s mainly because, Douthat thinks, Americans are becoming more lonely. He cites the very influential recent New Republic article by Judith Shulevitz that “reports that one in three Americans over 45 identifies as chronically lonely, up from just one in five a decade ago.” Studies show that there’s more than a bit of a loneliness epidemic. They also present new medical and neuroscientific evidence that loneliness is bad for your physical health. Not only can it lead to suicide in rare cases, it can lead to early death in other ways in lots of cases.

Loneliness is an increasingly formidable risk factor, and those “calculating probabilities” when it comes to staying around for as long as possible better work hard to avoid it. Gun suicides are now twice as common as gun homicides.

Maybe reformers should start saying that I, a (very late) middle-aged man, should vote for gun control mainly to protect myself from myself. On the other hand: Why shouldn’t we be pro-choice on suicide? As we extend lives in the direction of indefinite longevity, surely some people are going to need an exit option more than ever. But the “nudge economist” would object that maybe suicide shouldn’t be illegal, but we should still incentivize people not to be stupid.

None of these developments or discoveries would surprise our better evolutionary psychologists. According to Jonathan Haidt, the pioneering sociologist Emile Durkheim, who knocked himself out connecting suicide rates to being socially disconnected, was the most truthful of our social scientists. He even suggests that all his empirical work is pretty much a footnote to Durkheim. Asocial isolation is contrary to nature of “eusocial” animals such as ourselves, and so of course it would be bad for our mental and physical health. And the resulting feeling of insignificance or loss of purpose, it is easy to see, could lead to suicide.

Let me add quickly—as Douthat gets around to doing—that the evolutionary psychologists exaggerate the extent to which we only flourish as a part of social group. They don’t do justice to the free individual or the person. For instructive exaggeration in the other direction, read Ayn Rand or a Stoic philosopher. The repressive conformity of small towns can lead to suicide too.

Fewer thoughts are more simple-minded than “community” is the solution for “individualism” or the solution for “the repression of community” is “the autonomous individual.” It is reasonable enough to say that we almost always only find secure personal identity within a secure relational context, but that context doesn’t have to be all that “organic” or rural or even homogeneous. There’s such a thing as the global community of diverse, displaced persons, and we can even learn a lot about it from the Bible.

There’s quite the subtle but insistent partisan dispute over relative weight of the causes of our loneliness epidemic.

Shulevitz highlights the loneliness felt by both closeted and marginalized gays, as well as by those stigmatized by having AIDS. It’s true that if we all more open and accepting in these cases, some people might be a lot less lonely. Who can deny that we should all, in love or charity, act accordingly? It’s always true—but especially now—that loneliness is the worst form of poverty, which is why charity is better (if more unreliable) than welfare. (I’m not taking a public policy stand here—arguably we’d be better off with both.)

But quantitatively speaking, it’s clear that other causes of loneliness are more important. Douthat points to the erosion and instability of relational institutions—particularly the family, local community, and church. Haidt largely agrees. Haidt and Douthat (if you read this column in light of his others) blame our increasingly aggressive ideological individualism. It would be easy to go on talk about the decline of fatherhood, the “epidemic” of lonely single moms, the declining birth rate, and the surprisingly rapid rise of divorce among the middle-aged. The fastest rising demographic group in the country is men over 65 with no close connection to spouse or children.

A lot of the threaders, with some good reasons, object to Douthat’s deemphasis of economic causes for our loneliness. Surely the increasing inability of middle-class (especially lower middle-class) men to find decent jobs is a key cause of their detachment from their families, their churches, and their communities. The birth dearth did spike when the economy swooned.

Some blame welfare dependency for what’s happened to our relational institutions. When people come to rely on the impersonal government, they stop relying on their personal relationships. Others blame the global competitive marketplace for undermining the various safety nets that support personal or relational life (such as unions, “the family wage,” and so forth) and for making the workplace itself much more lonely. It’s possible, if you think about it, to blame both the excesses of socialism and those of capitalism.

I actually have a lot more. The good things about all the causes I’ve listed so far is that they all deal with what goes on in the relational context of real human lives. None of them suggests ridiculously that loneliness—like anxiety and other disorders listed in that psychiatric manual—is a merely chemical problem that can respond well enough to medicinal solutions. There’s no neuroscientific cure for loneliness on the horizon.

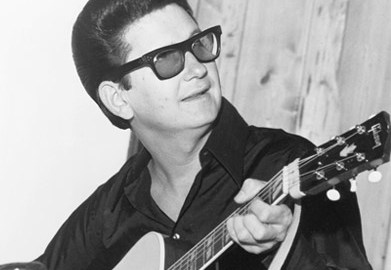

I would remind the lonely, as did the Boss, that Roy Orbison did sing for you. It wouldn’t hurt—and it might help—to listen.