Is Walter De Maria’s Death His Final Artwork?

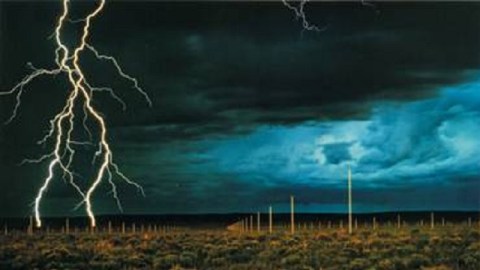

Walter, we hardly knew you. When I saw that American artist Walter De Maria had died at the age of 77 on July 25th, my mind’s eye immediate pictured The Lightning Field (shown above), the landmark 1977 installation piece that most art lovers know only through pictures thanks to its out-of-the-way location and strict visitation policy. De Maria brought a minimalist’s mind to the world of large-scale art, imposing a powerful will for precision on the natural landscape as a means of ordering it in a way for contemplation. De Maria, who shunned photography not only of his artworks but also of himself, may remain as enigmatic as his art now that he’s gone, but is his bodily passing his final artwork?

I’ve always wanted to read more about De Maria, but have always been thwarted. Here’s a man who not only created fascinating artworks, but played drums in a group with Lou Reed called The Primitives that eventually became The Velvet Underground. A frequent participant in all kinds of 1960s “happenings,” De Maria must have had stories to tell, yet he always let his art do the talking, or, I should say, the not talking. What Thomas Pynchon was (and still is) to modern American literature—a sphinx—, Walter De Maria was (and may continue to be) to modern American art. (At least Pynchon did an episode of The Simpsons.)

I’ve never been to see The Lightning Field in person. Nobody I know has. Trekking out to New Mexico during the 6-month period they take reservations to visit overnight is on my bucket list of art experiences, but not something I’ll be taking the kids to anytime soon. De Maria and his assistants set 400 pointed stainless steel poles exactly 220 feet apart from one another in a grid that measures 1 mile by 1 kilometer. The poles all stand at the same height regardless of the natural terrain’s differences, with some being only 15 feet high and others almost 27 feet high. In some ways, The Lightning Field is OCD of epic proportions. Art critic Robert Hughes put The Lightning Field on the cover of his American Visions as a powerful symbol of American art literally spreading itself across the New World landscape well into the 20th century. Although actual lightning strikes are quite rare, The Lightning Field captivates in all weather, turning everyday occurrences such as sunrise and sunsets into quasi-religious experiences.

I still remember reading (and reviewing) Kenneth Baker’s book titled simply The Lightning Field and coming away with more questions than answers. Paradoxically, Baker wrote an entire book about how The Lightning Field “silences the incessant prattle of consciousness.” That’s a lot of words to say that words fail me. Baker, however, soldiered on his best. Baker actually wrote an essay about the artwork when it first opened in 1977, but De Maria requested he suppress it because it was “too descriptive”—it gave you too good a picture of the field, and that wasn’t good, at least in De Maria’s eyes. Baker returned to the subject of De Maria’s field after 9/11, when, as he wrote, “many people conversant with the arts turn[ed] to them for consolation, [but]… The Lightning Field offers none. This confirms its importance.”

Baker dug deeper when he wrote, “The Lightning Field activates one’s submerged sense of the philosophical dislocations the past millennium has effected. After Copernicus, Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, and Einstein—and some might wish to add Heidegger, Foucault, and Derrida—humanity can no longer locate itself at the center of anything.” That’s a lot of name dropping to drop the essential idea that humanity can’t be certain of anything anymore. The uncertainty of The Lightning Field, its resistance to attempts to make it mean or symbolize something, makes it an important work and perhaps the most honestly representative artwork of the 20th century.

Closer to home, or at least closer to some person’s homes, De Maria created in 1977 (the same year at the field) New York Earth Room, a 3,600-square-foot SoHo New York loft filled 22 inches deep with rich, chocolate brown soil. Hughes included a trip to the loft in his television series for American Visions, probably because he couldn’t get permission to put The Lightning Field on film. There’s still that sense of wonder in walking up the steps of an apartment building and finding an entire room full of loam in the middle of SoHo. Yet, New York Earth Room always felt kind of sterile to me, as much as it tries to invade the urban jungle with nature’s presence. For practical reasons, De Maria had the soil treated to prevent anything growing in it, so the soil itself is lifeless. As much as De Maria and his work left an indelible impression on modern art, it really didn’t give life to any kind of follow up movement. There aren’t any De Maria disciples that I’ve heard of. De Maria’s a kind of dead end in that sense, but perhaps that was the way he wanted it.

But the artwork that struck me as the most De Marian of De Marias was his Art by Telephone. Created for a 1969 Swiss show titled “’When Attitude Becomes Form,” De Maria placed a black telephone on the floor with a sign that read: “If this telephone rings, you may answer it. Walter De Maria is on the line and would like to talk to you.” I wonder now if that phone ever rang. Did he really want to talk to us? Was it all a joke on the people who waited by the phone in vain? Characteristically, De Maria died in his sleep, perhaps from a second stroke suffered in California while visiting his mother on her 100th birthday. There’s a great silence to De Maria’s work, amazingly for a drummer, but De Maria always marched to that Thoreau-ian “different drummer” when it came to being an artist. In a world where artists always want to make so much noise about what they’re trying to tell us, Walter De Maria died as he lived—telling us nothing but making us think deeply about that nothing.