Robert Williams: Bitchin’ Art Crusader?

As artist Robert Williams grew up in his often dysfunctional, divorced home in the 1940s and 1950s, his mother wished he’d become a cowboy. After seeing Cecil B. DeMille’s 1935 filmThe Crusades (rereleased in 1948), however, young Bob decided on a career as a crusader instead. With a lion’s heart, fiercely wide-ranging intellect, and outsider’s eye, Robert Williams dreamed of a holy land where his unique brand of art would one day gain acceptance. Robert Williams: Mr. Bitchin’, now available on DVD and digital platforms, tells the story in Williams’ own words and pictures of that long, often lonely crusade to make art true to his experience that defied the mores of society at large and the art world in particular. Entertaining and enlightening, Robert Williams: Mr. Bitchin’ offers the rare chance to see the real-life good guy win in the end.

For an artist with so many accomplishments (and possibly the leader of a “movement” or “school,” although he’s leaving that up to posterity), Williams strikes you with an astounding lack of pretension combined with a profane disregard for the rules. During Mr. Bitchin’, Williams rides a bicycle and a unicycle and manages to fall off both. Watching him ride with the joy of a young boy, I couldn’t help but think of that great picture of Albert Einstein on his bicycle. I’m not calling Williams an Einstein, but I do think that there’s a connection between playfulness and genius that can’t be denied. Neither took himself too seriously, which freed them up to fail enough times to succeed in the end.

Williams’ irreverent lifestyle and art come straight out of the Southern California environment he’s steeped in since moving there in 1963. He credits the hot rods, outlaw bikers, psychedelic posters, underground comics, porn industry, and tattoo culture as all having an influence on him. “The West Coast was holding all the cards,” Williams says in the film, while the Midwest and East Coast held onto the “constipated” 1950s mindset. After art school, Williams resisted the limiting branding of “illustrator” and continued to follow his own path, stumbling eventually onto his “dream job” of working for Ed “Big Daddy” Roth studio and producing images for the SoCal hot rod crowd. Continually at his side was his wife, Suzanne Chorna Williams, also a working artist and hot rod enthusiast, but more importantly a kindred spirit with wide-ranging interests and ideas to help feed Bob’s visual landscape.

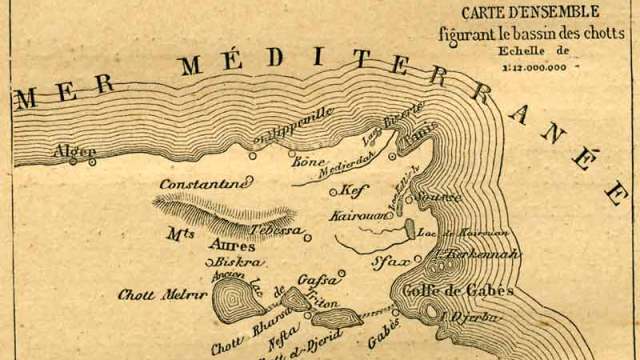

Throughout Mr. Bitchin’, you always feel a kind of challenge in Williams’ voice—are you capable of keeping up with him? Standing before one of his many “Super Cartoons”—meticulously painted works that portray an entire story in one panel—Williams is at one moment making you think about the Piltdown Man hoax and the general nature of deception, then the forgotten world of board track racing and the death of three racers at the Beverly Hills Speedway in 1920 and the nature of mortality and fame, and then King Farouk of Egypt as an embodiment of self-delusion. A great deal of thought goes into each of these works and, as several scenes show, a great deal of craftsmanship. For someone with little regard for rules, Williams respects the craft of painting deeply, stretching his canvas and sneering at those who use staples instead of tacks and reminiscing when “being a technical craftsman used to be part of being an artist.” The results can be mesmerizing, as in 1968’s In the Land of Retinal Delights (detail shown above), which smacks of Salvador Dali, but never surrenders, as Dali sometimes did, the idea of communicating an idea, however difficult or however obscure.

Williams finally found a larger audience when he joined ZAP Comix, an underground comic born in the anti-establishment age of anti-Vietnam War protests and the youth movement. Along with artists such as R. Crumb and Victor Moscoso, Williams’ comics became the gateway drug for many to come to accept his paintings as “real” art. “When I came into art,” Williams explains in the film, “cartoons were not considered art. But the cartoon is really the point where you can do the most exaggeration and really test and strain your imagination.” For Williams, the art found in E.C. Comics and pulp magazines contained an “energy that’s been lost in abstract art.” The stifling conformity of canonical art short-circuited art itself for Williams. “There’s a thing about ugly and distastefulness that’s really an aesthetic in itself,” Williams believes and then proves in the calculated ugliness and distastefulness of his work.

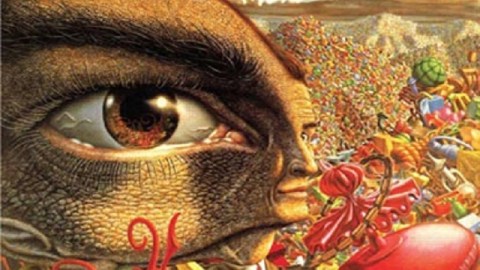

That ugly aesthetic brought Williams his biggest fame and infamy when Guns N’ Roses placed his painting Appetite for Destruction inside their album of the same name. Amid cries that the painting “glorified rape,” Williams responded that he was simply portraying the desires of actual life. Williams, who elsewhere painted a series of sexually potent women posed atop food items, recognizes human hungers of all kinds and puts them in his pictures, which can be read as exploitive, but which he (and his supporters) see as powerfully human.

By the end of Robert Williams: Mr. Bitchin’, you’ll be cheering for the artist, who not only never compromised on his ideas, but also gave back to like-minded artists by founding Juxtapoz Magazine, which publicizes “low brow” art in opposition to the more mainstream art magazines. Thanks to Juxtapoz, today’s generation of “outsider” artists can exhibit in galleries and survive without feeling the loneliness Williams’ did during his earlier career. When Juxtapoz co-founder Greg Escalantetearfully compares the impact of Robert Williams on modern art with that of the Beatles on modern music—and how both are unfairly discounted by history—you feel some of the tragedy of Williams’ struggles, but when you hear Williams say now in all honesty that he’s happy, you’ll feel better about life and art and believe again that the good guys, the true crusaders, sometimes do win.

[Image:Robert Williams. In the Land of Retinal Delights, 1968 (detail).]

[Many thanks to Cinema Libre Studio for providing me with a review copy of Robert Williams: Mr. Bitchin’, available on DVD and digital platforms starting July 30, 2013.]