As comedian Martin Mull (allegedly) once said, “Talking about music is like dancing about architecture.” Sound’s non-verbal qualities help it elude any attempts to pin it down definitively through the critical word. But that problem never has (and never will) stop people from trying. In Soundings: A Contemporary Score, which runs at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through November 3, 2013, visuals bravely venture into the territory where words typically fail. With their first ever major exhibition of the still relatively young genre of sound art, the MoMA hopes not just to bring this art form and its practitioners to a mainstream audience, but also to test whether sound art itself is a feasible art form for the masses. The real question humming in the background of Soundings is whether we’re ready to listen and look.

Sound art’s been on the rise recently. Susan Philipsz won the 2010 Turner Prize for Lowlands, an installation piece in which she hauntingly played a mournful old Scottish song over a stretch of open water. British artist Haroon Mirza has won several prizes as well, including the 54th Venice Biennale’s Silver Lion for Most Prommising Artist in 2011. Both Philipsz and Mirza appear in Soundings, along with 14 other prominent sound artists from around the world. Starting on September 10th, The Metropolitan Museum of Art will feature Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet, an installation by Canadian sound artist Janet Cardiff (who’s not in Soundings), as part of their 75th anniversary celebration at The Cloisters. If even the Met’s getting into the sound art act, going so far as to put the first contemporary art piece in the conservative setting of The Cloisters, there must be something to it.

Of course, Cardiff’s Motet’s not going too far out on a limb by using an 11-minute loop of the music of 16th century composer Thomas Tallis. Similarly, much of sound art looks and sounds like a recycling of Dadaism or Surrealism for today’s generation—similar ideas, but better technology to realize them. As cutting edge as sound art claims to be (and the art awards circuit seems to be recognizing), there some “been there, done that” qualities to the work, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t some interesting pieces (which you can see and hear at home through the MoMA’s extensive exhibition website).

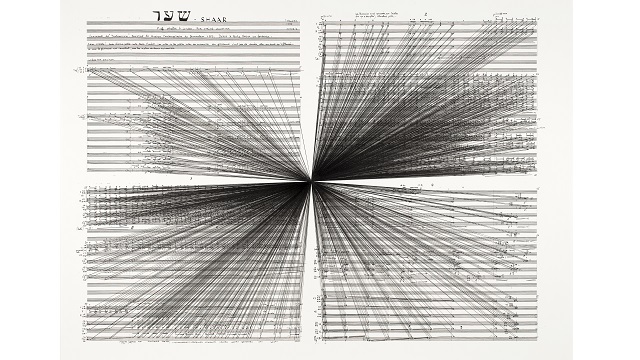

When you sit on Sergei Tcherepnin’s Motor-Matter Bench (2013), music plays through the wooden subway bench and into sitter’s body. You feel the music in a physical, visceral way that gives you a different awareness of sound itself. In a similar way, when you walk up to the 1,500 one-bit speakers of Tristan Perich’s 25-foot-long Microtonal Wall (2011), the individually tuned speakers give you a personalized sound experience. “Each listener’s exploration of that aural space shapes what they hear,” Perich explains, “from the totality of white noise (from a distance), to the single frequency of each speaker (up close).” Camille Norment’s Triplight (2008) transforms an old-style crooner’s microphone into a flickering light that, thanks to the metal ribs of the microphone itself, project a phantom rib cage onto the wall, as if a long-gone jazz singer’s ghost stepped up for one last song. Marco Fusinato’s Mass Black Implosion (Shaar, Iannis Xenakis) (2012; shown above) does its level best to give a visual equivalent to music itself. Mass Black Implosion is one of five drawings by Fusinato in which he took a single note of an avant-garde classical composer such as the Greek Xenakis and meticulously connected it to every other note, as if every note were to be played simultaneously in an implosion (explosion?) of sound.

But as much as the visuals of Soundings appeal, it’s the sound that makes sound art unique. Luke Fowler & Toshiya Tsunoda’s The Temple Recording 01 (2010) captures the peaceful sounds of a Japanese temple, while Stephen Vitiello’s Bell Study (2010) spookily captures the sounds of various resounding bells in an aural essay on and of “bell-ness.” As gentle and simple as Camille Norment’s Triplight lighted microphone (discussed above) looks, her 16-minute sound piece Toll (2011) takes a toll on listeners through sheer complexity and cacophony, mingling instrumentalists hammering on their instruments while fragments of Arvo Pärt‘s Fratres drift in and out of your consciousness. A 2006 trip to abandoned buildings near the site of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant site—now synonymous with nuclear disaster—led to Jacob Kirkegaard’s AION, where he recorded what should have been total silence but somehow resonates in the hearer’s mind as the very sound of radiation. A temple, bells, chaos, radiating energy—it’s all so very Zen.

But if Zen is Soundings’ strength, it’s also its weakness. The missing figure in all of this, and the unofficial founding father of sound art, is artist, composer, and Zen advocate John Cage. Cage remains the most significant influence on visual art and classical music of the 20th and 21st centuries, yet he’s almost entirely unknown by the general public. Similarly, sound art always seeks to strike a chord in the soul of the listener, but whether those souls are receptive is always the issue. Are we and our fast-paced society even capable of stopping and listening in the way these artists require? “At a time when the experience of sound is increasingly private—delivered through earbuds and headphones,” the MoMA website suggests, “Soundings is a communal exploration of how and what we hear, and what we might make of it.” Perhaps sound art is exactly what modern society needs, but that very need might be what keeps us from appreciating and experiencing it properly. The exhibition site invites people to share a “sonic moment” from their everyday lives as part of this “communal exploration.” Unfortunately, only eight moments have been shared (all from New York), making you wonder just how far this exhibit will reach.

Is Soundings: A Contemporary Scorejust more futile talking about music, dancing about architecture? Can the MoMA use its cache to bring sound art to a larger audience? Or will the brave few who pass through the gallery emerge more befuddled than before about what sound art is all about? We’re just not ready to sit and listen to the sounds of radioactive silence, no matter how much that silence tells us about the world around us and where it’s headed. Sound art might be the art form of our time, but paradoxically might be so timely in filling a void that it’s ahead of its time.

[Image:Marco Fusinato. Mass Black Implosion (Shaar, Iannis Xenakis). 2012. Ink on archival facsimile of score, Part 1 of 5 parts, 32.3 x 43.1″ framed. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne & Sydney.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to Soundings: A Contemporary Score, which runs through November 3, 2013.]