How Paul Strand Photographed the “People’s History”

When Howard Zinn first published A People’s History of the United States in 1980, he hoped to start a “quiet revolution” in the way people viewed history. By giving voice to the voiceless relegated to the wings of history while major players dominated the stage, Zinn wrote history in a wholly new, revolutionary way. Just as Zinn gave those people a voice, photographer Paul Strand gave them a face, but more than 60 years before. Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography at the Philadelphia Museum of Art traces the development of one of the founding fathers of modern photography in search of democratic ideals not just in his native America, but all around the world. Viewing the world through Strand’s lens will renew not just your faith in the power of art, but also your faith in the human spirit’s resilience regardless of time or place.

Strand’s long been recognized as part of the holy trinity of modern American photography along with Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. With such canonization sometimes comes complacency in interpretation—in Strand’s case, justified praise for his early work but unfair silence regarding later projects. This exhibition represents the first retrospective of Strand’s work since the 1970s, which also began at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 1980, Strand’s estate donated almost 500 prints from that exhibition to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Since 2009, the museum’s dedicated itself to acquiring almost 4,000 more prints and other items, thus making The Paul Strand Collection at the PMA the single largest Strand collection in the world. Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography celebrates that collection’s realization as much as the artist himself.

From the very beginning, Strand learned to link politics and photography. In 1907, Strand signs up for a class at the Ethical Culture School in New York City titled “Nature Study and Photography” taught by the progressive sociologist-photographer Lewis Hine. Hine took Strand and the class to visit Alfred Stieglitz’s “291” Gallery, an experience that, Strand would later claim, inspired him to become a photographer. Strand soon entered Stieglitz’s circle of artists, formed friendships with Georgia O’Keeffe and others, and studied new art movements coming over from Europe such as Cubism.

The young photographer then set out on a series of “experiments” with photography—itself a young, growing medium—up to the end of the 1920s. Amanda N. Bock, one of the curators of the exhibition, describes this time in her catalog essay as Strand’s “painstakingly slow and methodical exploration of genres”—everything from landscapes to “still lifes verging on abstraction.” Walking through this section of the exhibition you feel the restlessness of Strand’s eye as he moved from the strikingly honest “street portraits” taken of unaware subjects to the iconic, “Hopper before Hopper” Wall Street.

What holds this period together is Strand’s growing sense of modernism, both as an esthetic and as a human condition. Not for Strand was socially disengaged abstraction or just as disengaged “ironic street photography,” Peter Barberie, chief curator of the exhibition explains in the catalog. “For Strand,” Barberie writes, “realism could be woven out of fact or fiction, or both, but it had to say something tangible about the world.” The most “tangible” element in Strand’s early 20th century world was the increasing wave of modern machinery, which simultaneously excited with new promise and threatened with self-destruction. For the rest of his life, Strand pursued that modernism in different places and different people around the world.

Shocked by his own “street portraits” in 1916, Strand gave up portraiture almost entirely until the 1930s, when he traveled to Mexico and stayed for 2 years to photograph not only the local people, but also the bultos or devotional statues in their churches. Using the same prolonged exposure (sometimes up to an hour) that allowed him to milk every detail from his nature studies, Strand photographed these dramatic wooden statues of Christ’s passion to reveal every detail of the fabrics and even the spots where faithful fingers had worn away paint over the years.

Strand’s own prolonged exposure to the humanity of these people revealed to him new truths about the reality of modernism. “Attuned to modernity’s distinct inflections in different locales,” Barberie explains, Strand “wanted to show how time and history had shaped the present moment of each place he photographed… The realism he advocates involves, in his words, a dynamic approach to everyday life that engages the changing world, avoids treating subjects as immutable or timeless, and represents to ordinary people the conflicts and heroism of their own lives.” The search for that everyday heroism in the face of the challenges of modernism became Strand’s own heroic quest.

The exhibition gives ample room for us to follow Strand on his quest. Strand’s first book project, Time in New England (published 1950), explored the nature of American modern democracy in the cradle of American democracy itself. Strand and collaborator Nancy Newhall selected texts such as the last letters of condemned anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti to pair with the photographs of New England people and scenes to “evacuat[e] text and image of canonical and clichéd signifiers and giv[e] these concepts by threading them into a kind of ‘people’s history’ of the region,” argues Bock. The Great Depression’s effects on American culture and inequality radicalized Strand’s already leftist tendencies, leading him not only to such works as Time in New England, but also to leave American in 1950 for France, where he would live until his death in 1976. “McCarthyism” had not yet chilled free speech in American, but Strand sensed early on which direction the political winds were blowing.

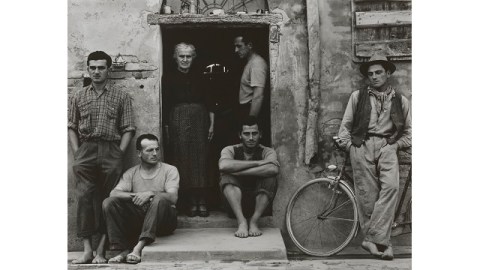

Both Barberie and Bock understandably tread lightly when it comes to Strand’s politics. Barberie calls Strand “undogmatic” politically, whereas Bock prefers “many degrees of left” to describe Strand’s ranging from FDR “New Deal” devotee to Communist curious. But I tend to see Strand as “political” in the original, ancient sense of the word, as pertaining to citizens rather than attack ads and gridlock. Bock quotes Strand idealizing over “an artist who is also a citizen,” something that he aspired to throughout his career all the way from the streets of New York City to Europe and finally to Egypt and to Ghana just as that sub-Saharan country was taking its first steps toward democracy in the 1960s. When you look at a picture such as The Family, Luzzara (The Lusettis) (shown above), taken during Strand’s time photographing the people of the Italian village of Luzzara, you could easily mistake these five brothers and their mother as Americans. The similarities are strong enough that nationality doesn’t even matter anymore. Strand evolved from American citizen to world citizen but never lost his sense of patriotism for the American democratic ideal he challenged his home country and all others to live up to.

Unlike so many other photography exhibitions that feel like you’re witnessing a disembodied eyeball at work, Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography makes you feel the presence of the artist throughout. The final room contains the actual cameras Strand used as well as photographs of him at work through the years, but it is the artifacts of his travels, such as the annotated map he and his wife used to navigate Ghana, that give you the full effect of his quest. Viewing the exhibit can be an exhausting experience simply from the intensity of this humanity that compels you to look closer at everything from the portraits to doorways dilapidated with character. Interactive kiosks that allow you to virtually page through Strand’s books now long out of print at first seem like modernist intrusions, but I could easily imagine Strand himself, ever the modernist, enthralled with the displays. Such a combination of humanism and modernism is the exhibition’s most fitting tribute to the artist.

Although Strand usually worked slowly in composing his images, one scene during his trip to Ghana made him impulsively snap away at a bus rolling by featuring the words “Never Despair” on the back. Those two words could be the emblem for all of Paul Strand’s life and work. “We like to photograph people who have strength and dignity in their faces,” Strand said of his and his wife’s work in Italy, “whatever life has done to them, it hasn’t destroyed them. They still have their own kind of humanity.” Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography demonstrates that no matter what happened to Paul Strand—even self-imposed exile—he kept his “own kind of humanity” that never despaired when Fascism, Communism, and even McCarthyism threatened democratic citizens at home and abroad. At a time when everything from Ebola to ISIS makes you question your faith in this modern world, Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography provides a beautiful reminder of what really matters and why it will always endure.

[Image:The Family, Luzzara (The Lusettis), 1953 (negative); mid-late 1960s (print). Paul Strand, American, 1890-1976. Gelatin silver print, Image: 11 7/16 x 14 9/16 inches (29.1 x 37 cm). Sheet (irregular): 11 3/4 x 15 1/16 inches (29.8 x 38.3 cm). The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with funds contributed by Lois G. Brodsky and Julian A. Brodsky, 2014. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for allowing me to attend the press preview for and for providing me with the image above and a review copy of the catalog to the exhibition Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, which runs through January 4, 2015.]