How Ebola is Messing With Our Brains

Human irrationality is nothing new. But sometimes we get a fresh reminder that the human capacity for clear thinking is hampered by all kinds of stumbling blocks, and that our elected leaders are hardly immune to them. This season, of course, that something is a curly little virus called Ebola.

The scene on Thursday in Fort Kent, Maine, had an absurdist cast: two slow-moving police cars followed a woman riding her bike with her boyfriend on a crisp autumn morning. Meanwhile, state officials tried to convince a judge to issue a quarantine order for the woman, Kaci Hickox, to prevent her from coming within three feet of anyone while out of doors and to keep her out of all businesses and public transit. (Today Judge Charles C. LaVerdiere did just that.) Ms. Hickox, a nurse, returned to the United States last Friday from Sierra Leone where she had spent a month caring for Ebola patients. Now her state’s governor, Paul LePage, says Maine must remain “vigilant” in protecting the public from Ms. Hickox, in case she is carrying the virus.

Maine authorities are not alone in seeking to quarantine healthy medical workers back from the Ebola front lines. A large handful of states, including New York, New Jersey, California and Louisiana, have imposed 21-day quarantine orders, the length of the incubation period of the virus. Chuck Hagel, the Secretary of Defense, made a similar move on Wednesday, issuing a mandatory on-base quarantine for members of the military returning from three West African countries where they had been building clinics.

The Centers for Disease Control, scores of medical experts and President Obama agree that there is no justification in medical science for these aggressive quarantines. There is zero risk that a symptom-free carrier of the Ebola virus can pass the virus on to another person. Only someone shedding fluids containing the virus poses a risk to others. According to the CDC, individuals who have treated Ebola patients should monitor their health for 21 days, including twice-a-day temperature checks, but there is no reason for quarantine unless someone actually contracts the disease. A more restrictive policy, the White House says, could ultimately be counter-productive:

The White House has argued that stricter measures adopted by states such as New Jersey and New York could hurt efforts to recruit doctors and nurses to volunteer their services in West Africa. The federal government’s guidance says only health care workers who have been exposed to Ebola directly, such as through a needle pin prick or by not having adequate protection, should face isolation.

The editorial board of the New England Journal of Medicine agrees with the president’s perspective. “The governors’ action,” they write in an editorial, “is like driving a carpet tack with a sledgehammer: it gets the job done but overall is more destructive than beneficial.” The way to stem the Ebola tide is to attack the virus in West Africa, not to attack the volunteers who are returning from that fight. “These responsible, skilled health care workers who are risking their lives to help others are also helping by stemming the epidemic at its source. If we add barriers making it harder for volunteers to return to their community,” the New England Journal of Medicine concludes, “we are hurting ourselves.”

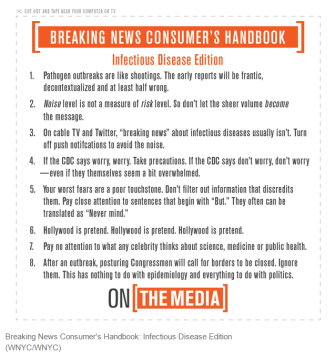

This chart gives a helpful summary of how not to freak out in the wake of Ebola’s arrival on American shores:

As useful and as sensible as these guidelines are, Ebola fever (the metaphorical variety) is unlikely to ebb any time soon. This is true for one simple reason: Ebola is scary. Under the right circumstances, it is highly communicable, and it kills about half of the people it infects. But people tend to fear Ebola with an intensity that is disproportionate to the actual threat it poses. Four people have come down with Ebola across the United States in recent weeks. Four. Of those, two have recovered, one is in treatment in a New York City hospital, and one,tragically, has died.

Why the outsize concern about a disease that is, by any account, very much under control? The answer comes from a 2001 study, “Risk as Feelings,” by psychologist George Loewenstein et al. The authors argue that “emotional reactions to risky situations often diverge from cognitive assessments of those risks.” When our fear gets the better of us, and wall-to-wall cable news coverage helps to encourage this, we make poor decisions. For example, the authors cite a 1993 study finding this:

“[P]eople were willing to pay more for airline travel insurance covering death from ‘terrorist acts’ (a highly imaginable event) than death from ‘all possible causes’ (which, of course, implicitly subsumes terrorist acts in addition to a range of other causes but does not spontaneously bring fear-provoking mental images to mind). At the opposite extreme, people tend to be underinsured against hazards that evoke relatively pallid mental images. Flood insurance is notoriously difficult to sell, even when premiums are heavily subsidized.”

Ebola is like terrorism: bloody, spectacular, fearsome and unlikely. Influenza, on the other hand, is like a car accident: common, boring, meh and thousands of times more likely. So everyone tends to worry about the wrong thing, and this misconstrual of risk is far from costless. A handful of Americans may contract Ebola in the coming months, but thousands will come down with the flu virus and think they may have Ebola, overwhelming emergency rooms and diverting medical resources from diseases and ailments that pose a far greater risk to the public health.

Stirring hysteria and locking up health workers willy nilly is a sad symptom of the predictably irrational response to a sprinkling of Ebola cases in the United States. We are all predisposed to overreaction; I admit have been draining my hand sanitizer bottle at a faster clip since news broke of the first Ebola patient in New York. I’ve also been eyeing fellow subway passengers with coughs more suspiciously. But our public officials and the media have a responsibility to temper these irrational fears, not to stoke them. Too many cable news anchors, and too many governors, are failing us.

Image credit: Shutterstock