How This Controversial Ad Helps Break the Taboo Against Discussing Female Menstruation

A recent National Public Radiopiece told the story of a 14-year-old Nepalese girl named Kamala. Like many Hindu women in western Nepal, Kamala is banished from her home and from normal social interactions during her menstrual period. For a week or so each month, Kamala sleeps on a platform outside in a leaky, thatched-roof menstrual tent with no walls. She does not touch her family members during this time, or eat in their company. This practice of “chaupadi” was banned by Nepal’s Supreme Court a decade ago, but it persists in many villages. Menstrual segregation, fueled by a belief that women on their periods contaminate everything they touch or approach, is a hard habit to break.

It’s about 7,400 miles and a century of advances in women’s equality from the Achham District of Nepal to the urban jungle of New York City, but the menstruation taboo is apparently oblivious to boundaries.

A year ago, two NYC teens (one of whom I’m proud to call a former student) made news for developing a video game designed to get people talking about menstruation more openly. Tampon Run, which you can play here, begins with a manifesto:

“Most women menstruate for a large portion of their lives. It is, by all means, normal. Yet most people, women and men alike, feel uncomfortable talking about anything having to do with menstruation. The taboo that surrounds it teaches women that a normal and natural bodily function is embarrassing and crude.”

The tampon-tossing game was a hit not for its stunning graphics or elaborate challenge — it was Sophie Houser’s and Andrea Gonzales’ collaborative project for Girls Who Code, a summer program teaching young women how to program — but for its message. And judging by a recent kerfuffle over ads in the New York City subway, it’s a message that has yet to spread widely enough.

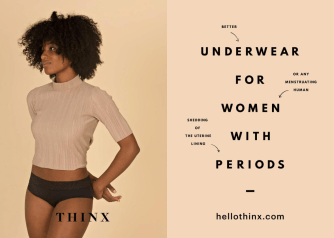

Thinx, a women’s underwear company specializing in knickers that absorb menstrual blood, proposed a subway campaign featuring ads like these:

One part capitalism, two parts public service, the ads contained messages designed to sell a product while exposing and helping to ease the shame surrounding a monthly fact of life for several billion people on the planet. But when the guys at the company that screens ads for the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) had a look, they had their doubts. In an exchange with Thinx, a spokesman for Outfront Media mentioned that the ads “seem to have a bit too much skin.” He called into question other ads depicting a vulval grapefruit and a dripping egg, saying that both “regardless of the context, seem inappropriate.” Finally, the media company was apparently queasy about the very inclusion of the word “period” in the copy. The representative “was concerned that children would see the word ‘period’ in the ad and ask their parents what it meant.” And when the marketing director for Thinx objected that these concerns seemed to propagate the very taboo the ad campaign was targeting, Outfront Media replied, ‘This is not a women’s issue. Don’t try to make it a women’s rights thing.'”

A furor rightly erupted over this sexism-spiked, poorly reasoned resistance. As Danielle Tcholakian remarked in a great post at DNAinfo, “[t]he subway system has plenty of ads that focus on women’s breasts, butts, and mostly naked bodies in general.” It is the height of hypocrisy to approve these sexually tinged ads, including ubiquitous banners advertising breast-enhancement surgery, while questioning the propriety of the Thinx ads. I mean, look at this one, which graces many a subway car in NYC:

I would much rather have one of my daughters ask me what a “period” is than grill me about the perils of small breasts or about what makes a woman’s body “ready” for the beach, or what weight-loss supplements have to do with living a healthy and happy life.

It appears the MTA may have been listening (and cringing?) as Twitter rang out with criticism of the (ironically named?) Outfront Media reaction to the Thinx ads. Following a barrage of incredulity, an unnamed MTA spokesperson told The New York Times, “Of course they will be approved.” That’s good news, if it’s true. But the whole affair demonstrates anew how uncomfortable the world seems to be with a biological process that’s essential to the reproduction of the human species — and how women pay the price.

—

Steven V. Mazie is Professor of Political Studies at Bard High School Early College-Manhattan and Supreme Court Correspondent for The Economist. He holds an A.B. in Government from Harvard College and a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Michigan.

Image credit: shutterstock.com

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie