Variety Is Key to Healthy Bodies—and Societies

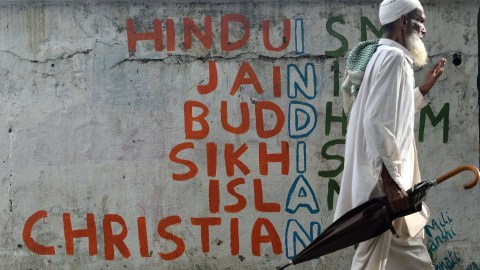

Four year ago the hypothesis that all humans will look Brazilian in a few decades exploded. The ‘Earth melting pot’ theory stated that global homogenization is fast approaching as cultural interbreeding continues. While this merging of societies appears beneficial—it’s hard to be racist or xenophobic when you’re a little bit of everything—is this trend socially and cognitively healthy?

Variety is essential for our growth. In 2001, neuroscientist Rodolfo Llinás speculated on how the Internet would alter societies. While he recognized communication benefits from the emerging web, he foresaw dangers of mass group-thought. American-style consumerism bombarding Asia and Africa were not trends he believed healthy. The trite, he writes, is easier to copy than ideas requiring deep thought. He continues,

We are fast approaching a world culture of sameness not only in the external trappings, but also the character and values of societies…The true downside to homogenization is a decrease in variation, and variation is the key to survival.

If everyone agrees on events the lack of options will suffocate. The collective mind, he writes, must partake in trial and error, learning as it—we—goes along. Homogenization stunts this process.

Of course, the world has not panned out that way, yet. The Internet has revealed a variety of ideas previously unimagined. Credible sources might be sparse—one downside is the proliferation of junk science and conspiracy theories—but variety is no problem if you’re willing to look around.

But are we? Eli Pariser (among others) has warned of the dangers of a filter bubble. Holding nuanced ideas in your mind is rarely respected as an honorable skill. The reverberations of the ‘with or against us’ mentality that made liberals cringe last decade echoes on the feeds of millions.

Let’s trace Llinás’s theory back a few steps, as variety is key in individual and collective growth. In I of the Vortex he posits the notion that thinking is a form of movement based on prediction. Early multicellular organisms navigated toward or away from other organisms based on predicting where they needed to eat, reproduce, and avoid danger. Regardless of how distant this feels, this is where we began.

Cycle through a few billion years and you arrive at humans, which have internalized this evolutionary drive in the form of thinking. Thoughts are movements; every time you have one, your motor neurons fire. Though thinking is an internalized activity, it still affects neurons that physically move you. In fact, if you just imagine doing a bicep curl, those specific neurons fire.

Movement is critical to our survival. Sure, this is hard to understand if you’re hunched over a computer or stuck in a car all day. Yet you’ll pay for poor movement patterns in the form of anxiety, obesity, disease, and memory loss as you age. People who move more frequently tend to have a higher quality of life.

This is where it our brain’s love of conflict ruins us: from the perspective of energy, it will always choose the path of least resistance. Why walk a mile when I can drive? Why walk a block when I can Uber? In terms of energy management this is understandable. The conflict: our brain craves movement—remember, that is how it was designed—especially diverse, complex movements. Variety makes it stronger.

In his book Spark, Harvard psychiatrist John Ratey calls brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) the “Miracle-Gro of the brain.” Like societies, your brain thrives on diversity. Navigating your environment requires a variety of specialized movements and thought patterns. The more time you spend learning new movements, the more time you spend thinking differently to navigate your environment, the more you adapt. The more BNDF grows.

When BDNF is released, it does not simply affect newly created pathways or existing motor neurons. It floods the entire brain. This is why diverse movement is so important. It helps everything, all at once, including neurotransmitters implicated in helping people with addiction and depression. It helps you remember better, longer. It also helps loosen the grip of anxiety, one of the most prominent issues facing us today.

We don’t often associate thinking with movement, unless you happen to an athlete. Researchers like Llinás and Ratey recognize that the internalized world we inhabit closely mimics the external reality we create: the communities we embed ourselves in, the people we share our life with, those we communicate with online. This dialogue between thinking and our environment is mediated by movement.

And the more variety we introduce, the better for ourselves, and the world we live in. I’d personally take no issue with everyone looking Brazilian—that is quite a beautiful culture. But if we all thought like Brazilians (or any other culture) trouble would ensue. Debate, criticism, and skepticism are essential components of a healthy brain and body. And society.

Llinás’s fear regarding the web we’re weaving might not pan out, though given this partisan American election cycle, variety is harder to find: with us or against dominates. Challenging yourself physically and mentally with new movement patterns is a surefire way to stave off homogenization. The important thing is to consistently challenge yourself in both your interior and exterior worlds. Then growth is not only possible, but guaranteed.

—

Image: Indranil Mukherjee / Getty Images

Derek Beres is a Los-Angeles based author, music producer, and yoga/fitness instructor at Equinox Fitness. Stay in touch @derekberes.