How Boys’ and Girls’ Brains React Differently to Stress

There is an old saying in education that girls cry tears while boys cry bullets. In other words, females are allowed in our society to express their vulnerability and less pleasant emotions such as sadness. While boys must remain stoic and shoulder the burden quietly or else get angry, and express their pain not through outbursts of emotion, but instead through action. Might there be a biological phenomenon behind these culture-based roles? A study published online in the journal Depression and Anxietysuggests so. It found that boy’s brains react differently than girls in the aftermath of a highly stressful event.

Researchers at Stanford University discovered this by scanning the insula, or insular cortex, of boys and girls who had PTSD and comparing them to those who didn’t. This is a region deep within our brain responsible for integrating emotions. Feelings and the sensation of pain are processed here. It is also where empathy emanates from. The insula takes in data from other parts of the body and related areas of the brain, and incorporates it all into emotions and actions.

This is the first study to denote a gender difference in how the brain reacts to PTSD. In girls, the insula developed or aged rapidly. The same process was not observed in boys. Victor Carrion, MD was the study’s author. He is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the university. Dr. Carrion told the Stanford Medicine News Center that this particular region played a key role in PTSD’s development. “The difference we saw between the brains of boys and girls who have experienced psychological trauma is important because it may help explain differences in trauma symptoms between sexes,” he said.

This is a substantial breakthrough, as it could help neurologists develop personalized treatment options for PTSD sufferers depending on gender. With children and teens, while some who are exposed to a serious trauma do develop PTSD, others don’t. Researchers still aren’t sure why that is. They do know that girls are more likely to develop it than boys.

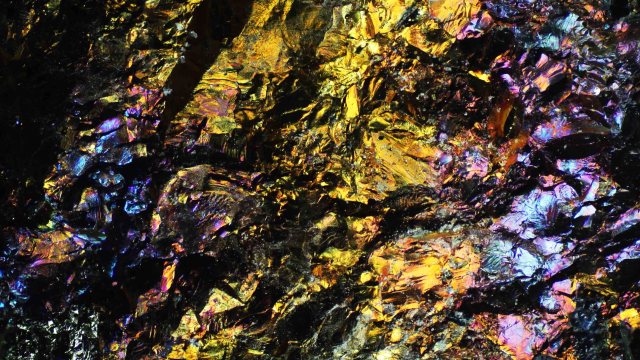

Anatomy of the insula (insular cortex). By Mani Pavuluri, Amber May, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In this study, the brains of 59 participants, each between the ages of nine and 17, underwent MRI brain scans. 30 of them had PTSD. Another 29 took part as a control group. 16 boys and 14 girls had suffered trauma, while another 14 boys and 15 girls had not. Normal participants showed no differences in insula structure, regardless of gender. Of those who were traumatized, five participants experienced one episode of severe trauma, while 25 had been exposed to two or more episodes. Researchers tried to match up participants and controls, comparing those of a similar age and IQ.

The area within the insula that changes due to severe trauma is known as the anterior circular sulcus. Researchers discovered that while in traumatized boys this area grows larger than normal, with girls it shrinks. Another way to look at it is its development accelerates. These changes in structure are thought to be integral to PTSD’s development. The shrinkage seen in female brains may be the reason why girls are more prone to PTSD.

Dr. Megan Klabunde was the study’s lead author. She told the BBC, “Our findings suggest it is possible that boys and girls could exhibit different trauma symptoms and that they might benefit from different approaches to treatment.” She added that high levels of stress might lead to early puberty in girls, as some previous studies suggest. This breakthrough may also help neuroscientists understand how each gender processes emotions.

Now, Dr. Carrion’s team will scan and examine other brain regions to see if they too change in structure after significant stress. Another project is long-term, ongoing studies following traumatized young people over time, to explore how PTSD may affect their brains as they grow older, with a special focus on developing gender specific treatments to counteract such changes.

To learn more about PTSD, click here:

—