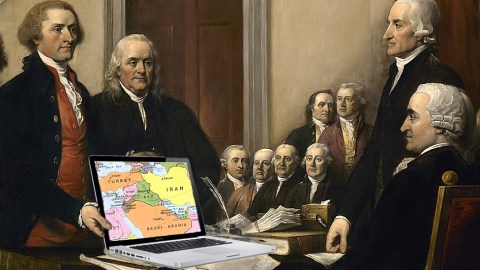

What Would the Founding Fathers Think of Modern America’s Foreign Policy?

More than 200 years ago, the United States were founded by disgruntled colonial men wearing ruffled shirts and tri-corner hats. Their writings on government structure and democracy have endured, but what about their views on global affairs?

The Founding Fathers’ general approach to foreign policy began with Thomas Paine’s ‘Common Sense‘. In his famous 1776 pamphlet, Paine made the case that political connections with the outside world—especially with Britain, the dominant power at the time—should essentially be limited to commerce:

“As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no partial connection with any part of it. It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions, which she never can do, while, by her dependence on Britain, she is made the makeweight in the scale of British politics.”

Oil painting of 18th century Enlightenment philosopher and author Thomas Paine by Auguste Millière (1880); Common Sense, a pamphlet by Thomas Paine (1776).

The Founding Fathers had subscribed to Paine’s view during the Revolutionary War, but eventually found that an alliance with France was necessary in the short term. Then, in 1793, George Washington effectively broke the alliance with his Proclamation of Neutrality.

Washington doubled down on his support of American independence in his Farewell Address of 1796, believing there to be an inherent danger in becoming overly entangled with other countries, namely the risk of becoming too lenient on allies, and too harsh on their enemies:

“The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.”

…

“Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots who may resist the intrigues of the favorite are liable to become suspected and odious, while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people, to surrender their interests.”

The early nation’s views on foreign policy were solidified in 1821 when John Quincy Adams, then the secretary of state, delivered an address on U.S. foreign policy that outlined why the country wouldn’t get involved in the Greek War of Independence:

“Wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will recommend the general cause, by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example.”

Speaking at the Cato Institute in 2016, William Ruger, Vice President for Research and Policy at the Charles Koch Foundation, delved into the views of Washington, Adams, and others, remarking: “States don’t have permanent friends, they have permanent interests, and the Founders were hyper-realist when it came to that.”

Three Decades of American Primacy

The U.S. has been the world’s most powerful nation since the end of the Cold War. Some refer to this position as “American primacy,” which political scientist Joseph Nye defined as its “disproportionate (and measurable) share of all three kinds of power resources: military, economic, and soft.” While this power has allowed the U.S. to create an advantageous world order, America’s interventions abroad have come at massive human and economic cost.

Ruger spoke to Big Think about the consequences of U.S. foreign intervention:

“Primacy has often led the United States to create situations where there’s greater instability, more problems, lots of unintended consequences that have spilled over to other places. And Iraq is a perfect example of that. ISIS would not exist in Iraq had it not been for the United States opening Pandora’s box by our regime-change efforts.”

As the U.S. enters its third decade of primacy since the end of the Cold War, it’s worth returning to the thoughts of the Founding Fathers, and how they conceptualized America’s role in the global community. What would they have thought about invading, say, Iraq? In Adams’ words, is it a monster the U.S. should have gotten mixed up with?

The Founding Fathers’ Views Today

It goes without saying that the world today is far more complex than it was 200 years ago. Technology and industrialization have connected the world in entirely unpredictable ways, and the power of the U.S. has multiplied to an unimaginable extent. There’s also a case to be made that with America’s great power comes the responsibility to right the many wrongs in the world.

However, the massive costs of U.S. foreign policy over the past couple of decades have caused some to call for realistic restraint, which argues for the U.S. to fully consider the consequences of intervention before entangling itself in the problems of other countries, as Ruger explains:

“Over the last 15 to 25 years, our foreign policy simply isn’t working. It is not making us safer. And that’s why we need to reconsider what we’re doing. We need to rethink our grand strategy. We need to rethink how we’re using diplomacy and economic levers of statecraft. We need to rethink our budgets and the types of platforms we’re building and the types of missions we want to send our troops on.

This is vitally important so that we can rightsize the military for the challenges ahead. And I don’t think we’re doing that, which is why we need to bring new voices into the conversation. The other thing I think that we should ask for is: we would like our executives to practice humility. That means that they need to understand what they don’t know, and to have that be part of the decision-making process.”

Still, a more realistic and restrained foreign policy doesn’t mean the U.S. should engage in full-blown isolationism and abandon the rest of the world, Ruger says:

The United States needs to be engaged abroad in terms of trading with other countries, providing positive-sum outcomes between peoples, diplomacy, cultural engagement, people to people engagement. We can be engaged in the world and open to the world without thinking that the United States needs to be everywhere and without the United States having to lead and be militarily deployed to every part of the globe.

We can never know exactly what the Founding Fathers would think about modern U.S. foreign policy. However, we can tell from their speeches and writings that they all seemed to agree on a general principle: be extremely wary of becoming overly entangled with the never-ending problems of the outside world.