Frozen in a swamp, fearsome ancient warrior’s hidden tomb is revealed

The Uyuk River Valley in the Russian republic of Tuva has been known to archeologists for some time as the site of ancient princely tombs belonging to fearsome and tattooed horse-riding nomadic troublemakers referred to by historians as the Scythians. The area is known as the “Siberian Valley of Kings,” and in it are a group of burial structures, or “kurgans,” built on river terraces. Archeologists have named them Arzhan 1-5, and Chinge-Tei 1. Now there’s Tunnug 1, lying frozen and buried in a swamp along the Uyuk River. It’s the earliest Scythian kurgan ever found, and may also be the most undisturbed, thanks to being so well-hidden in this already-remote region, and through preservation from permafrost. Bern University archaeologist Gino Caspari recently published Tunnug 1’s discovery in Archaeological Research in Asia.

Tunnug 1 was spotted by Caspari as he examined high-resolution satellite images. He wasn’t the first to notice its mound — that was M. Gryaznov in 1980 — but Caspari was the first to identify the object as a kurgan. A summer 2017 dig with the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Hermitage Museum provided confirmation. The kurgan contains wooden beams that date it back to sometime before 900 BCE, about hundred years earlier than neighboring Arzkhan 1, which was built as 900 BCE gave way to 800 BCE.

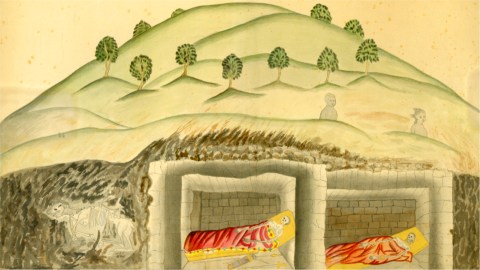

When Arzkhan 1 was excavated in the 1970s, it was found to have a single internal structure of wooden chambers arranged radially. They were in a good state of preservation, and relatively intact, containing weapons, horse harnesses, and art objects decorated in the Scynthian animal style. The larch-wood structure was topped with a package of large flat stones serving as a roof. The area’s other kurgans, excavated later, share a similar structure, though Chinge-Tei 1 has a deep, 106-meter diameter moat around it.

Aerial photographs of Tunnug 1 were taken in 2013. Tunnug 1 is the large circular area in the bottom right.

(SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION)

From there, a Swiss National Science Foundation-funded partnership of the University of Bern and the Hermitage Museum and the Russian Academy of Sciences ordered high-resolution satellite imagery with a grant from the Digital Globe Foundation. From those images, a digital model accurate within 4 centimeters, as well as ortho-photographs of the site, were generated to help the team make decisions about the most promising areas to explore.

In the ortho-photograph above, the sparsely vegetated areas are “most likely collapsed wooden chambers which were covered with logs and a layer of stones. The logs broke and the stones fell into the chambers creating stone-filled pits. Plants are not growing on top of the pits because the stone package drains the water and no substrate is available.”

The Russian Cultural Heritage Administration forbids the digging of exploratory trenches prior to full excavation but allows the cleaning of destroyed or covered portions of the kurgan. The team pinpointed several areas for cleaning as shown by the red bars here.

Tunnug 1 is the largest frozen kurgan ever found Eurasia. Here’s what the team thinks is beneath the surface in Area 1 above.

During the expedition last summer, pottery shards were found at the surface, though it’s suspected they belong to other groups, as multiple uses of burial sites is not uncommon in the area.

There’s some sense of urgency to get Tunnug 1 excavated, thanks to climate change: If the permafrost has the chance to melt, as the study says, “treasures are in immediate risk of being lost.” That would be terrible: This is a tantalizing find that could provide such a unique, well-preserved glimpse into these legendary tribes of fierce ancient warriors.