How to curb the opioid epidemic? Tell doctors which of their patients died.

On January 27, 2017, a letter went out to 388 doctors stating, simply:

“This is a courtesy communication to inform you that your patient [name, date of birth inserted here] died on [date inserted here]. Prescription drug overdose was either the primary cause of death or contributed to the death.”

It was part of simple yet innovative experiment, one designed to answer the question: Will physicians become more judicious in their opioid prescribing habits after they receive personally tailored letters alerting them that one or more of their patients had died from the medication?

The study was published Thursday in the journal Science. For the study, researchers led by Jason Doctor of USC’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics selected 388 physicians who had “prescribed a schedule II, III, or IV drug to a person who died as a result of a schedule II, III, or IV accidental overdose between the period of 1 July 2015 and 30 June 2016 in San Diego County.”

The researchers then sent these doctors a carefully crafted letter, which they described as “supportive in tone” and designed to alert the doctors of the deadly potential consequences of opioid prescriptions—not to accuse them of playing a direct role in the patient’s death. Most patients had received prescriptions from multiple doctors.

In the three months after the ‘courtesy communications’ were sent, physicians who received letters reduced their prescribing of opioids by about 10 percent and started about 7 percent fewer patients on a new opioid regimen.

“It’s sort of a process,” study co-author Dr. Jonathan Lucas, who signed the letters and has since become Los Angeles County’s chief medical examiner, told the Los Angeles Times. “If we had extended the study period out to a year or so, we probably would have seen a bigger difference.”

This kind of blunt, emotional approach could become regular in the battle against the opioid epidemic. San Diego, for example, is already planning to roll out an initiative to send letters to doctors when their patients die of an overdose, and Los Angeles is considering doing the same.

“I have to imagine it’s gut-wrenching,” said Dr. Sean Michael, a University of Colorado emergency physician who’s studied opioid prescribing habits but was not involved in the study, told the Los Angeles Times. “The job that everybody is trying to do on a daily basis is the exact opposite of this outcome. The intention when people wrote these prescriptions was to try to help someone, not to accidentally kill them. But that’s the problem: The edge is so narrow and the risk is so high with these medications.”

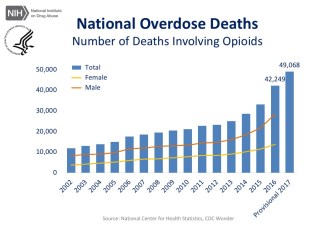

The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that more than 115 people die every day in the U.S. from overdosing on opioids, including heroin, prescription pain relievers and synthetic opioids like fentanyl. It’s a trend that’s increasing at a disturbing rate, according to Robert Anderson, chief of the mortality statistics branch at the National Center for Health Statistics.

“We’ve gone well beyond [the AIDS epidemic] now,” he told the Washington Post. “It’s hard to take in.”

In 2017, about 49,000 people died from opioid-related causes. Alarmingly, that number might be conservative: A study published in June described how some states report unintentional drug overdose deaths as ‘unspecified’, and estimated that as many as 70,000 of these unspecified overdose deaths from 1999 to 2015 might be attributable to opioids.