Lack of basic research hiding behind ‘clean meat’ hype

- Tens of millions of dollars are funding projects to create a consumer-ready lab-grown burger.

- Despite the hype, experts warn that a lot more research needs to be conducted.

- Mainstream adoption of plant-based foods, however, is making lab-grown meat a welcome possibility.

Few people disagree that a better solution to factory farming needs to be implemented. Yet since the stark realities of living conditions on such farms are hidden, most people go about their lives without thinking too much about the meat they’re eating. Verbiage scrawled on packaging is not much help; terms like “free range” and “all natural” are effectively meaningless. Consumers deserve better, for health and ethical reasons, but it’s hard to define “better than what” when “what” is poorly understood.

Lab-grown meat sets off alarm bells in skeptics, yet as Paul Shapiro, author of Clean Meat, told me last year, an educational process is needed. Combine ethical decisions with biological integrity and lab-grown meat could be a clear winner. Omnivores get tasty protein while vegetarians and vegans can indulge without guilt.

There is certainly a desire for it. Mosa Meat, which has stated its products will be made available in restaurants by 2021, raised nearly $9m for its efforts; plant-based producer, Beyond Meat, has amassed $72m in investment. The Good Food Institute recently funded 14 projects with $3m in grants to companies developing lab-grown meat and plant-based protein. Another research organization, New Harvest, has invested nearly $1m to fund projects over the last decade.

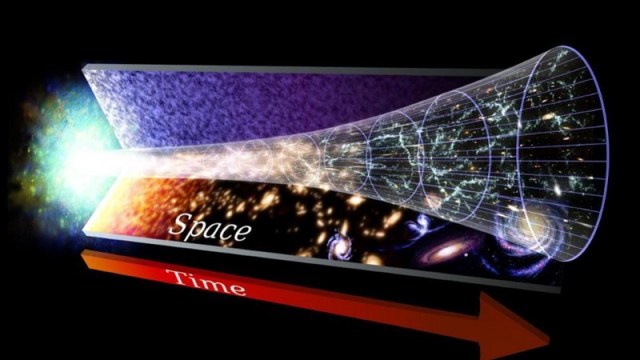

Beyond animal cruelty, the resources needed for producing meat is environmentally taxing. Methane production and water usage are both staggering. The pluripotent stem cells that serve as the basis of laboratory protein could be a silver bullet addressing many problems simultaneously.

But is the hype blinding us to the science? A new article in Nature states we might be.

Tasting the World’s First Test-Tube Steak

According to the article, some projects are falling by the wayside as well. While the Dutch government agreed to contribute $2.3m for research, legislators ended up focusing their efforts on plant-based proteins. This is unfortunate, given the additives used in many such products.

For example, take the popular Beyond Meat burger. While the three main ingredients (besides water, which is the top ingredient) are canola and coconut oils and pea protein isolate, what follows is a list of preservatives necessary for binding, appearance, and taste. These include methylcellulose, a laxative used as an emulsifier; maltodextrin, which is problematic for diabetics; gum arabic, which, in high doses, has been linked to “harmless flatulence.” Perhaps most troublesome is “natural flavor,” which essentially means, “whatever we want and we won’t tell you.”

Granted, at less than 2 percent, none of the added ingredients are likely to harm you, but for a company advertising itself as a “revolutionary” product that “looks, cooks, and satisfies like beef,” we have to question what is being used to mimic that effect. There are other companies producing alternatives sans preservatives—Sunshine Burgers, for one, makes delicious veggie burgers—so settling on overly processed foods seems a poor choice.

For the moment, lab-grown meat remains in the minor leagues. Like Beef 1.0, when produced this new form of meat will not need additives for consumption. Yet cost is still too prohibitive. As the Nature article cites, a 140-gram burger costs roughly 500 Euros while a thin slice of steak costs roughly $50. Few people will pay premium prices at a sustainable rate; perhaps novelty satisfies a curious itch, but that’s where we’re currently at. Until the prices are comparable to what we currently consume scalability is impossible.

Meatless ‘Impossible Sliders’ sit on a table at a White Castle restaurant, April 12, 2018 in the Queens borough of New York City. The meatless burgers, which sell for $1.99, are about twice the size of White Castle’s regular sliders. The patties, made primarily of wheat protein and potato, are the first plant-based burgers sold in an American quick-serve restaurant. (Photo illustration by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Another hurdle in spreading the gospel of lab-grown meat is tradition. Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture, Ryan Quarles, recently commented that while the state supports new technologies, he wants to make sure no one is “fooled” by marketing campaigns. According to him, Kentucky citizens prefer meat “that comes from four hooves.” While this displays an ignorance of how cells are cultured and grown, the barrier to entry for many omnivores is high. Vegetarians and vegans will likely be the initial target market for widespread adoption of such products.

Still, we need alternatives. Right now, 30 percent of calories consumed by humans around the world comes from meat products. In the past half-century, we’ve nearly doubled our meat consumption as a species. In a growing population that’s a lot of carnage; estimates range from 56b animals to many times more that killed just to satisfy our cravings.

Becoming a lab-grown meat-eating species will likely only occur out of necessity, which, mind you, is a possibility. That said, an industry is waiting. As SuperMeat chief executive, Ido Savir, states in the Nature article, “a new field of science is here.” It’s an exciting one, but a lot more research and testing remain before a consumer-ready product arrives. We can hope for 2021, but we have to be ready to accept reality over hype should it not pan out that way.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.