How storytelling gives life meaning

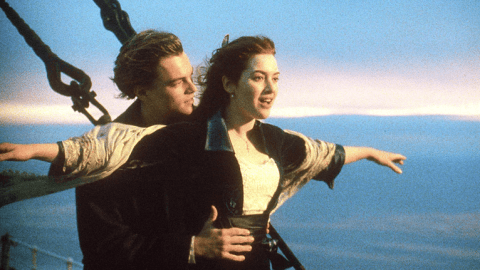

Still from James Cameron's 1997 film, Titanic.

- “An experience of being alive” is what mythologist Joseph Campbell said humans strive for.

- Though we live in an age of distraction, short videos still tell big stories.

- That said, losing a connection to the environment to stare at a screen has disastrous consequences.

In the opening moments of an epic dialogue between Bill Moyers and Joseph Campbell, Moyers mentions the means by which mythology provides guidance. Death is a certainty, a fact humans have long struggled with. These timeless stories provide a framework for discovering a meaning of life by aiming beyond the grasp of the every day. Storytelling is an art; narrative provides instruction.

Campbell replies to Moyers: the mythologist doesn’t believe we’re seeking a meaning of life, but rather “an experience of being alive.” Our life experiences need to resonate beyond the physical plane to align with our “innermost being and reality,” for then we can “feel the rapture of being alive.” Mythologies provide such sustenance, as “clues to the spiritual potentialities of the human life.”

Recitation of stories is an ancient inheritance. Across the planet, students learn and pass along their traditions through epics. Retelling your culture’s narrative is pivotal in the construction and dissemination of your heritage. Identity relies on the transmission of the story of your people. Even today, recitation remains an integral aspect of Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism, even if it is predominantly scholars studying the extant literature. The underpinnings of culture relies on these stories.

The Quran is the source of much frustration for outsiders; for example, a recent edict in Brunei calling for the death of homosexuals. But this is not representative of every Muslim, as often perceived in America. The actual recitation of Islam’s holy book is stunning. The call to prayer, blasted out through tiny speakers, binds the community, providing context for existence.

I think often about how stories are transmitted. The life we live is achieved through the stories we tell ourselves; these stories are influenced by those we consume. Living in the Age of Distraction, with so many forces competing for real estate in the attention economy, it seems the deep knowledge offered through the slow process of storytelling is being wiped away.

An AFP collaborator poses for a picture using the smart phone application TikTok on December 14, 2018 in Paris. TikTok, is a Chinese short-form video-sharing app, which has proved wildly popular this year. Photo credit: AFP / Getty Images

In some ways, it is. It requires enormous mental fortitude to memorize the 100,000 śloka (couplets) in the Mahābhārata. Yoking your mind to such a task pays off tremendously in terms of memory retention and life satisfaction. Americans read an average of a dozen books per year — good that we’re reading, though not the most impressive number. Yet there are other ways to tell stories.

As an avid reader, my initial reaction to the emergence of self-styled videos as a means of storytelling was negative. That feeling has shifted over the years, mostly because it’s merely a different medium for expressing creativity. The latest platform for quick, snappy storytelling, TikTok, has surpassed 500 million users and has been downloaded a billion times. The stories told on this platform don’t require focused attention, yet that does not mean they lack creativity. In fact, conveying meaning in 15 seconds is challenging. Yet this story about a mother vaccinating her children offers plenty of meaning in just a few snapshots.

With an army of songs, filters, and sounds at the user’s disposal, TikTok offers easy access to potential creatives. The only limitation, as has been poetically expressed for millennia, is your imagination. As with every medium, branded content and stars emerge atop the feed, but the democratizing of narrative afforded by this medium is reminiscent of an old trend in storytelling from biblical and Upanishadic times: the story is more important than the author.

Of course, it doesn’t always play out that way. There is plenty of evidence that our shrinking attentional economy is driving increased rates anxiety and depression. Addiction is addiction, regardless of medium. While there is much to celebrate in the technological progress we’ve made at communicating and relating, one key piece is absent.

In his book, Landmarks, Robert McFarlane discusses additions and deletions from Oxford University Press’s junior dictionary. Gone are words like acorn, beech, dandelion, hazel, and willow. Added: blog, broadband, celebrity, cut-and-paste, voice-mail. Shifting environments is the excuse offered by one editor. But, as McFarlane puts it,

“There is a realism to her response — but also an alarming acceptance of the idea that children might no longer see the seasons, or that the rural environment might be so unproblematically disposable.”

Robert Macfarlane: Do children in the UK spend enough time outdoors? – BBC Newsnight

We are products of the environment. Like a lost child, we’re finding ourselves powerless in the face of climate challenges. Until we begin naming these struggles for what they are, we’ll continue to flounder.

Reality requires language to be understood and communicated. What we lack for in words we cannot convey. McFarlane’s homage to “nature words” reminds us that what we delete from our shared stories is a loss to the collective imagination. A few examples of words that capture nearly indescribable sentiments:

- Rionnach maoim: the shadows cast on the moorland by clouds moving across the sky on a bright and windy day

- Slogger: the sucking sound made by waves on a ship’s side

- Kimmeridge: the light breeze which blows through your armpit hair when you are stretched out sunbathing

- Glassel: a seaside pebble which was shiny and interesting when wet, and which is now a lump of rock, but which children nevertheless insist on filling their suitcases with after a holiday

One word instead of 31: a true economy of language. An entire novel expressed in seven letters; an autobiography in two syllables. Telling a story through a phone camera is one thing, but putting down the phone to explore the surroundings is a story we’ve been telling as a species for millions of years.

There is still only so much meaning that can be expressed in 15 seconds. Explore nature for a lifetime and still you will never exhaust its catalog.

Joseph Campbell was amazed that cultures that never had contact told the same stories around the same time; he cited Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious as means for such narrative dissemination. Today I can transmit a video of one of my cats rolling over and yawning around the planet in seconds. A fun break, certainly, but void of contact with the earth and wind and waves that have informed our stories for so long — life will always only be a few inches big, and we’re so much more than that.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.