John Pringle: The 18th-century doctor who saved countless lives — and destroyed a family

- John Pringle instituted sanitary reforms that saved lives on the battlefields and beyond.

- Today, he is celebrated for his medical service, but evidence suggests he was immensely abusive in his personal life.

- How appropriate is it to celebrate his accomplishments in light of his misdeeds?

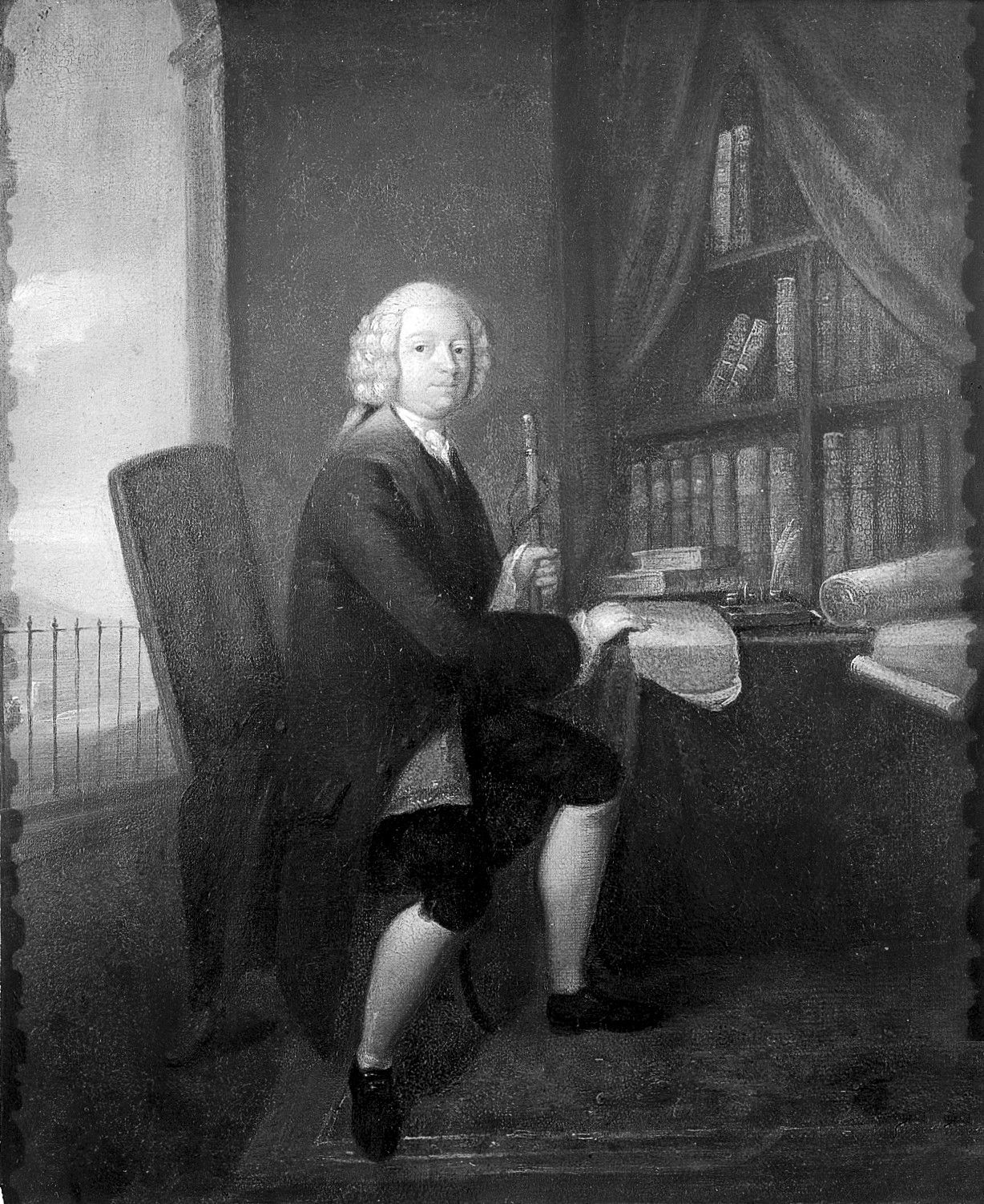

If you happen to look up sometime at the facade of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in Bloomsbury, you might notice the name “PRINGLE” in large, raised letters. John Pringle (1707–1782) belongs there by all the conventional rules of greatness. A military physician and pioneer of sanitary reform, he saved thousands of lives in the mid-eighteenth-century military campaigns in which he served. His work helped inspire the urban sanitary reformers of the nineteenth century and thus indirectly saved millions.

That’s what I was thinking about when I celebrated Pringle in early drafts of my book Ending Epidemics — A History of Escape from Contagion. But one day, I was doing further research in the papers of the diarist and biographer James Boswell, who was a friend of Pringle’s. At the bottom of Boswell’s handwritten 1782 eulogy for Pringle, preserved in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I came across a gossipy note, not intended for publication, on a particularly dark chapter in Pringle’s life. It’s hardly news that the great names of past and present often prove problematic on closer inspection. Boswell, for instance, was an active proponent of slavery. And Pringle? Let’s start with who he seemed to be in the public eye.

Pringle and the campaign against filth

As the youngest son of minor Scottish aristocracy, Pringle had gone out into the world with good social connections and an elevated sense of his own status but little income to sustain it. He studied at Leiden University, then the center of medical learning in Europe. Back in Scotland, he earned respect, but not much more, lecturing at Edinburgh University.

Pringle seems not to have won over students, or anyone else, with his personal warmth. A portrait by Joshua Reynolds depicts him with thin lips pressed tight, right eyebrow flaring up impatiently at the outside. He “paid a very respectful attention to those who were honoured with his friendship and esteem” and to those who came to him “well recommended,” Boswell noted in his eulogy. But he disdained “that false and superficial politeness which treats all men alike, though ever so different in point of real estimation and merit.” He was, that is, a snob.

With the coming of war in 1742, Pringle sought a commission as an army doctor, in an apparent bid to improve his income. He had no military experience, but John Dalrymple, the Earl of Stair, was a family friend and commanding officer of the British forces in Europe. Pringle soon won an appointment as the physician-general to the entire British force of 16,000 men. In this case, patronage would prove fortunate.

In June of 1743, British forces defeated the French at Dettingen in Bavaria. Back home, patriots sang “A Bloody Ballad on the Bloody Battle at Dettingen,” the blood having flowed mostly on the French side. Pringle was less inclined to rejoice, having been caught up throughout the campaign in the far greater mortality away from the battlefield.

In the aftermath of combat, 1500 deathly ill British soldiers had made their straggling way north to the army’s general hospital in Fechenheim, on the outskirts of Frankfurt. There, men lay packed head-to-toe in every bed and on the floors of nearby cottages. Most of the sick had dysentery, and everything was inevitably covered with excrement, urine, blood, sweat, and vomit. Fleas and lice abounded. When an outbreak of typhus, then called “hospital fever,” began, Pringle blamed “foul air from crowds and animal corruption.” This fit that era’s conventional medical faith in humoral theory, which held that sickness resulted when certain forces, usually atmospheric, caused the four bodily “humors” to become imbalanced. At Fechenheim, Pringle wrote, the air “became vitiated to such a degree, that not only the rest of the patients,” but the hospital staff and villagers “were also infected.” Hundreds died. Throughout the 1743 campaign, the British army lost a quarter of its strength to sickness alone. In short, it was warfare as usual.

Pringle set out to change that. During the next two years of fighting in Europe, he worked through the military command to turn his insights into orders: Quartermasters were to avoid campsites in damp, poorly ventilated areas. They were to send an advance patrol to prepare proper latrines before the arrival of the soldiers who would need them. During the dysentery season, from mid-July on, the latrines should be deeper than usual, covered daily with a layer of dirt, and sited so the wind would “carry off their effluvia from the camp.” Pringle recommended a small, “but strictly inflicted,” penalty “upon every man that shall ease himself any where about the camp, but in the privies.” This emphasis on cleanliness and sanitation would prove life-saving.

In military hospitals, Pringle mandated that patient space was to be clean, well-ventilated, and with a minimum of 36 square feet of space for each man, ending the practice of crowding two or more men in the same bed. Bed linens were to be changed frequently. These reforms quickly paid off, reducing mortality at the general hospital by more than half, from 21.4 percent in 1743 to 9.8 percent over the next two years of fighting.

From the battlefield to the boroughs

Returning home, Pringle established a practice in London and parlayed his military service into a career as a physician to the nobility. In 1754, he published his book Observations on the Diseases of the Army. It went through four editions over the next dozen years, spreading Pringle’s sanitary gospel through the British military and, in translation, to its French, German, and Italian counterparts.

The fourth edition, published in 1764, hinted at a more modern understanding of infectious disease. Pringle now recognized that scabies, a skin disorder, resulted not from effluvia but from “certain small insects” (actually mites, which are a type of arachnid). He had by then also encountered a “curious dissertation” from Carl Linnaeus, the pioneer of the scientific system of naming and classifying species. Linnaeus favored an early theory that certain infectious diseases might be caused by “animalcula” — the sort of tiny microscopic life-forms first revealed decades before by the Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. This forerunner of the germ theory of disease was highly speculative, but Pringle lent it a degree of credibility by taking note in his book. “It seems reasonable,” he concluded, “to suspend all hypotheses, till that matter is further inquired into.” The rest of the fourth edition, based on humoral ideas, remained unchanged.

The other great advance Pringle sought in his book was to extend his ideas about military hygiene to the urban environment. He attributed the incidence of “malignant fevers and fluxes” largely to cities being “low and ill aired; unprovided with common sewers; or where the streets are narrow and foul; or the houses dirty; where fresh water is scarce; where jails and hospitals are crowded and not ventilated, or kept clean,” and where shallow burials or livestock slaughterhouses corrupted the air with their effluvia. The problem, as in the military, was filth.

Without the military’s command structure, however, Pringle seems not to have seen a way forward for urban sanitary reform. Moreover, he was now established both financially and socially among London’s intellectual elite. In this company, he could be charming, even witty, and perhaps a bit complacent. He became a close friend and traveling companion of Benjamin Franklin. (“Here is a fine contrast: acid and alkali,” Boswell joked.) Other members of the intelligentsia would often join Pringle at his home in London for his Sunday evening salon. Like Stephen Maturin, the ship’s surgeon in Patrick O’Brian’s sea novels, Pringle enjoyed playing cello with friends.

From this perspective, London looked just fine. “[O]ne of the least subject to malignant fevers, the dysentery, or other putrid diseases,” Pringle wrote, though he acknowledged that certain matters relating to health “might be better regulated.” Among poorer people living in moist areas, “spotted fevers and dysenteries are still to be seen,” though “seldom heard of among the people of better rank, living in more airy situations.” Overall, he thought, “some of the main points are already attended to; such as regard the privies, the common sewers, the supplies of fresh water; and the people in general are very cleanly.”

Pringle could not know that the industrial revolution was already beginning or that, in the coming century, the rush of country folk to work in new factories would leave London more crowded and chaotic than a military encampment in wartime. It would turn the Thames into a sewer and fill hospitals with the sick and dying. It would also spur a great sanitary awakening, of a sort Pringle’s work foreshadowed, and ultimately turn London into a model of urban reform for the world.

A complicated portrait

Pringle was thus, fair enough, a great man. The small problem I ran into at Yale’s Beinecke Library was a marriage so brief and insignificant that biographers, as recently as 2014, have failed even to mention it. In 1752, Pringle arranged to marry the daughter of William Oliver, M.D., also a prominent military physician. Charlotte Oliver was 24 years old, and Pringle 45.

A note I came across in Boswell’s papers, just a line or two, referred to the “unhappy marriage” and to Dr. Oliver’s “severe verses after the Ladys death.” At a time when divorce was impossible, Charlotte had obtained a deed of separation from Pringle after little more than a year. She died soon after, at 25.

Boswell’s comment led me to the February 1754 issue of the Universal Magazine, where Dr. Oliver’s poem appeared under a pseudonym, couched in the language of a pastoral dialogue. It was full of the bitterest sort of grieving and recrimination. A heartbroken father recounted how a “sly deceiver,” breathing “amr’ous sighs” had led him to expose his daughter, his “tender plant,” to her seducer, who then “re-assum’d/His native fierceness, and with boist’rous rage/ And storms incessant, laid thy bloom all waste …” The culprit with his “northern blasts” was unmistakably Pringle, as much of London society must have understood. Perhaps they also knew whether the alleged abuse was physical or emotional. Either way, Charlotte Oliver Pringle was dead, and Pringle’s reputation endured up to this day, unsullied.

The more I thought about this, the less willing I was to celebrate that reputation in my book. I argued against this reluctance as I revised and edited Ending Epidemics. Was it fair to judge Pringle based on 250-year-old evidence of marital abuse? Did it outweigh the good he did as a physician? I worried about lapsing into “presentism,” the scholarly sin of applying modern morality to a very different time. I wondered if I was just overreacting to recent news about the perennial ability of the aristocracy to get away with murder, sometimes literally. In the end, though, the evidence felt persuasive. Grieving fathers do not write such stuff on a whim. No doubt the great military physician’s name could live on in large raised lettering on the frieze of the prominent Bloomsbury building. But I cut that chapter from the book and consigned John Pringle to my wastebasket.