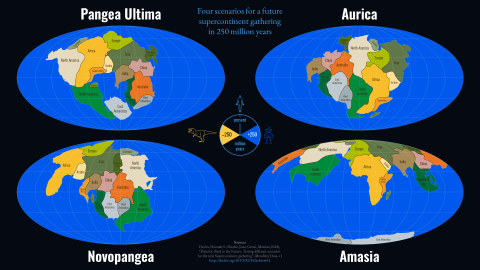

Four scenarios for the next supercontinent

Credit: Pilgrim-Ivanhoe, reproduced with kind permission

- We’re halfway through a ‘supercontinent cycle’.

- The next one is due in 200-300 million years.

- Here are four plausible scenarios of what it will look like.

How the American, African and European continents once fit together before the Atlantic – and may one day again, if and when the local ‘Wilson cycle’ reverses. Credit: Jacques Kornprobst, after E. Bullard et al. (1965), CC BY-SA 4.0

For things so massive and seemingly immovable, continents are pretty hard to pin down. Of course, that’s because they do move, if only at the speed at which your fingernails grow: about two inches (5 cm) per year.

Accelerate the film of Earth’s geology, and you see the landmasses dance across the globe like islands of foam on a running bath. One peculiarity of our drifting continents is that they tend to combine, over massive amounts of time, into one single supercontinent. It helps that the Earth is round, unlike your bath.

Then, millions of years later, tectonic forces cause the supercontinent to break up again – only for the individual continents to recombine much, much later. All at fingernail speed.

Norwegian map of what the supercontinent of Columbia/Nuna may well have looked like, 1,590 million years ago.Credit: Bjoertvedt, CC BY-SA 3.0

Here’s one question with an un-pin-downable answer: How many supercontinents have there been in Earth’s deep past? At least three or at least seven; as many as 11 or perhaps even a few more. Like the continents themselves, scientific theories diverge. Here are some of the usual suspects (most recent first, ages are approximate):

- Pangea (300-180 million years ago)

- Gondwana (600-180 mya)

- Pannotia (630-540 mya)

- Rodinia (1.1 bya-750 mya)

- Columbia, a.k.a. Nuna (1.8-1.5 billion years ago)

- Kenorland (2.7-2.1 bya)

- Ur (2.8-2.4 mya)

- Vaalbara (3.6-2.8 bya)

That’s if we spool back the tape. What happens if we fast-forward? Even though Pangea, the last supercontinent, broke up almost 200 million years ago, geologists are pretty sure there will be another one, but not for some time to come. Right now, we’re about halfway through a ‘supercontinent cycle’. The next one will be around between 200 and 300 million years from now.

John Tuzo Wilson (1908-93) refined and championed the theory of plate tectonics in the 1960s, when it was still controversial. He was the first non-U.S. citizen to become president of the American Geophysical Union.Credit: UC Davis

That brings us to the next question with an answer that’s hard to pin down: What will that next supercontinent look like? That is, of course, unknowable, as no one alive today will be around to check. But one can speculate. Using what we know about the tectonic forces that power the movements of continental plates, three scientists line up four plausible scenarios for the formation of the next supercontinent.

In “Back to the future: Testing different scenarios for the next supercontinent gathering,” Hannah S. Davies, J.A. Mattias Green, and Joāo C. Duarte present four supercontinents, each the outcome of a different tectonic what-if.

Each scenario is a different combination of two basic drivers of continental conglomeration (and fragmentation): the supercontinent cycle itself, and the so-called Wilson cycle.

In 1966, Canadian geologist John Tuzo Wilson proposed that the Atlantic had opened up along a zone where another ocean had previously existed. A ‘Wilson cycle’ therefore describes the cyclical opening and closing of ocean basins. Since those aren’t necessarily in sync with supercontinent cycles, they can lead to various outcomes – supercontinents of different shapes and at different types.

The next supercontinent will take shape when at least one ocean closes. That can happen in one of two ways:

- Introversion: the ‘internal’, expanding ocean starts to contract and closes up again; or

- Extroversion: the ‘exterior’ ocean keeps expanding, closing an ‘internal’ ocean elsewhere.

In the first option, the Wilson cycle and the supercontinent cycle coincide, creating the possibility that the new supercontinent will have more or less the same dimensions as the old one. In the second option, the Wilson and supercontinent cycles do not coincide.

In their paper, the researchers line up and standardise the evidence for four well-known scenarios on future supercontinent formation:

- The closure of the Atlantic Ocean, leading to Pangea Ultima;

- The closure of the Pacific Ocean, giving rise to Novopangea;

- The closure of both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, creating Aurica; and

- The closure of the Arctic Ocean, forming Amasia.

‘Ultimate’ Pangea would be a remake of the ‘old’ Pangea, more or less. Credit: Pilgrim-Ivanhoe, reproduced with kind permission

‘Ultimate Pangea’ will come about via an introversion scenario, with the closing of the Atlantic and the re-formation of the ‘old’ Pangea – sort of. Introversion is the ‘classic’ scenario for supercontinent formation; in fact, Pangea itself was likely formed by introversion, with the closing of the Rheic and Iapetus Oceans.

Africa is the key continent here; first by colliding with Europe to form the new continent of Eurafrica, and ultimately as the keystone tying South and North America, Europe and Asia together. Remnants of the Atlantic and Indian oceans reincarnate as the ‘ultimate’ Mediterranean, closed off from the world ocean by East Antarctica.

How Novopangea might come to be: the Pacific closes and a new ocean forms along the East African Rift.Credit: Pilgrim-Ivanhoe, reproduced with kind permission

A ‘classic’ extroversion scenario leads to the closure of the Pacific Ocean, and to a ‘new’ Pangea – not just a re-forming of the old one. The East African Rift keeps growing, developing into a new ocean, replacing the Indian one. East Africa gets stuck against India’s west coast.

Two Wilson cycles in sync with a supercontinent cycle, and hey presto: Aurica.Credit: Pilgrim-Ivanhoe, reproduced with kind permission

The Aurica scenario presupposes two Wilson cycles in sync with the supercontinent cycle. Both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans close, helping to form the supercontinent of Aurica, with the Americas in the middle.

This requires the opening-up of at least one new ocean – for example, at a large rift along the present-day border between India and Pakistan. This new Pan-Asian Ocean, merged with the Indian Ocean, pushes these areas apart, turning them from next-door neighbors into lands on either side of Aurica.

Australia is now entirely landlocked, between Antarctica, East Asia, and North America. Europe and Africa have collided with the Americas from the other side. To the south, Madagascar stubbornly continues its separate course.

In the Amasian scenario, almost all continents would be joined ‘at the top’.Credit: Pilgrim-Ivanhoe, reproduced with kind permission

The Arctic Ocean closes. Almost all continents are joined at the ‘top of the world’, with the exception of Antarctica, the only one not drifting northward. It’ll be a short hop from North America to North Africa, with Southern Europe acting as a land bridge in between. South America has repositioned itself, with its western edge against the eastern flank of North America.

These images produced by Pilgrim-Ivanhoe, reproduced with kind permission. Original context here. Images based on the aforementioned article: Back to the future: Testing different scenarios for the next supercontinent gathering, by Hannah S. Davies, J.A. Mattias Green and João C. Duarte, published in Global and Planetary Change (Vol. 169, October 2018).

Strange Maps #1064

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.