New Study: Some Sciences Really Are Better Than Others

If you want to rile up a biologist and have no pointed stick handy, try this: Tell her that chemistry or physics are “harder,” more fundamentally “sciencey” sciences than hers. “You can’t use the standards of one science to judge another,” she might say. “Physics is different from biology, not better.” Not so, you answer: There must be standards common to all the sciences, which some meet better than others do. You’re now set up for a seemingly unresolvable philosophical debate. Most working scientists I know would rather face the pointiest of sticks.

In this paper, published earlier this month, Daniele Fanelli tries to take the issue out of the realm of philosophy. He argues that there is indeed a “hierarchy of sciences” from hard and rigorous down to soft and fuzzy. And that this is not a philosophical position, but an objective fact, quantified by scientific methods.

Irritating as it is to unphilosophical scientists, the issue is unavoidably important. Science is supposed to describe reality, after all. And a reality in which all sciences are equal is different from a reality in which some are better than others.

To see why, consider not what scientists know, but what they don’t know. What’s the nature of these gaps in their knowledge? To put it roughly, answers fall into two camps.

I’ll call one Camp Give-Us-Time. Here, science is a bit like a commuter waiting for a bus: He does not know when the bus will arrive, but that’s only because of where he happens to be standing at the moment. The bus’s arrival time is certainly knowable, just not known today. All ignorance is temporary. Just Give Us Time, we’ll make scientific knowledge complete. “There is intrinsically only one class of explanation,” E.O. Wilson wrote in the Bible of Camp Give-Us-Time, Consilience. “It traverses the scales of space, time and complexity to unite the disparate facts of the disciplines by consilience, the perception of a seamless web of cause and effect.”

I’ll call the other side Camp Incommensurate. Over here, science is like a IT worker trying to understand behavior on a computer network, where millions of users, machines, lines of code and pieces of hardware all interact. Knowing the code doesn’t tell you anything about what’s happening with the hardware or that clumsy user’s coffee cup that tilted onto his keyboard. So, faced with a question like “Why did we crash that one time on Tuesday?” she uses programming skills to look at the code and hardware tools to examine the machines and social skills to look at the users. It may not work, though, because when software, hardware and people interact, things happen that could not be predicted by knowing each part separately. That means some questions cannot be answered, ever. Rather than a consequence of lack of money or brains or time, ignorance is a fact about reality itself.

I call this side Camp Incommensurate because of what follows from acceptance that knowledge is fragmented: These campers don’t expect different parts of science to fit together. Different fields are incommensurate, in that they don’t line up into a coherent whole. Why should psychology’s concepts, theories and methods be expressed as biology? And why imagine that you can break biology down into chemistry? We have psychology precisely because biology can’t account for the soul; we have biology because there are aspects of life that chemistry cannot grasp. The philosopher Jerry Fodor didn’t think much of the consilience idea for this reason: “In fact, there are very few examples so far in which it has turned out that the explanatory apparatus of a higher-level science can be paraphrased in the vocabulary of some science further down,” he wrote. Instead, as he put it, our heterogeneous fragments of knowledge might arise from “the heterogeneity of levels at which the world is organized, and both might well prove irreducible.”

Things are different back at Camp Give-Us-Time. There, they hold that psychology is too a subset of biology, which is a subset of biology, which is a subset of chemistry, which is a piece of physics. That means there is (to put it roughly) a single “right” way to do science—or, at least, a single standard against which to judge all research. The “hierarchy of sciences” follows from this assumption that knowledge is a coherent, reflecting a completely intelligible universe.

So I see Fanelli’s paper, published this month in the journal PLoS One, a bold raid by Camp Give-Us-Time on their opponents.

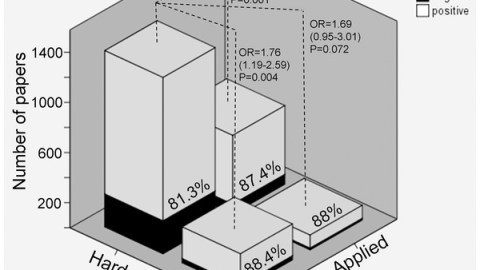

Here is his argument: If there is indeed a hierarchy of sciences from “hard,” rigorous disciplines down to “soft” ones, he says, then “researchers in ‘softer’ sciences should have fewer constraints to their conscious and unconscious biases, and therefore report more positive outcomes.” According to his analysis of 2,434 papers from the Essential Science Indicators database, that hypothesis was confirmed: “the odds of reporting a positive result were around 5 times higher among papers in the disciplines of Psychology and Psychiatry and Economics and Business compared to Space Science, 2.3 times higher in the domain of social sciences compared to the physical sciences, and 3.4 times higher in studies applying behavioral and social methodologies on people compared to physical and chemical studies on non-biological material.” (Yet there were more positive results in chemistry and physics than in papers published under the rubric of Social Science, so maybe the hierarchy needs some surprising revisions.)

At least the softer sciences can console themselves with the thought that they’re doing it right, according to Fanelli’s analysis: “On the other hand, these results support the scientific status of the social sciences against claims that they are completely subjective, by showing that, when they adopt a scientific approach to discovery, they differ from the natural sciences only by a matter of degree.” Perhaps he means it benignly, but I suspect that over in Camp Incommensurate, them’s fightin’ words.

Fanelli, D. (2010). “Positive” Results Increase Down the Hierarchy of the Sciences PLoS ONE, 5 (4) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010068