Is Technological Magic Infantilizing Us?

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

It could be argued that the technology on which we depend in our daily lives doesn’t evolve so much as simply grow. “Evolution” suggests a primitive form that’s slowly replaced by a more advanced generation. But these systems — power grids, the computers we use each day — accumulate complexity over time. New capabilities are tacked onto previous iterations without clearing out older technologies, complexities, and workarounds. And that’s a real problem, as author Samuel Arbesman’s book Overcomplicated makes clear. Arbesman says we’re living in a new “age of Entanglement,” and he’s not talking about the quantum kind: He’s talking about the kind that you can’t make your way through. A thicket full of thorns, a tangle of dusty, fraying wires.

Thorny situation

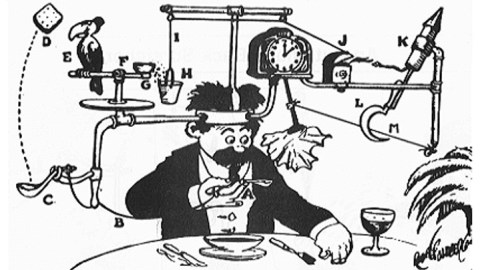

Think about air travel. Yes, it’s great we can see where we are in a constantly updated map on the back of the seat in front of us, it’s amazing we can check in online and receive updates, and the logistics involved in sending crews and planes where they’re needed across the U.S. are mind-boggling. But when the system does down, as Delta’s recent outage shows, the whole Rube Goldberg device is so complicated, so cobbled-together from mismatched old and new components, that just figuring out where the problem resides is a nightmare.

According to Arbesman in The Atlantic, this kind of thing is pretty much inevitable now, and it leaves us more vulnerable to chaos than we may realize.

“When the world we have created is too complicated for our humble human brains, the nightmare scenario is not Skynet—the self-aware network declaring war on humanity—but messy systems so convoluted that nearly any glitch you can think of (and many you can’t) can and will happen. Complexity brings the unexpected, but we realize it only when something goes wrong.”

Consider just a single software application. How many coders have worked on Microsoft Word? It’s a classic example of software that keeps adding functionality without ever going back to to fix what’s already broken. And who can blame its current stewards? They’d have to dig through layers and layers of ancient code and comments by programmers who long ago moved on to other things. Why not go back to Square One occasionally? Apple has done that a few times — iMovie, Pages, Final Cut — and been savaged for replacing featured-packed apps with fresh versions that traded beloved features for a clean reboot. So, no wonder most companies don’t bother. They just keep adding new code on top of the old.

Now imagine how many such programs must be working in tandem to maintain our power grid or air-travel system, each contributing its own impenetrable complexities to a system that is thus totally mystifying in the aggregate. No one person could possibly understand all of such a complex system. Parts, sure, but the whole thing? No way. Is this really okay?

LAX (TIM BRAY)

Another issue Arbesman cites is technology companies’ desire to create a simple “it just works” experience. In the effort to hide the magic under the hood, any chance for users to understand what’s actually going on is also jettisoned, so that if something goes wrong, well, it just does. It’s infantilizing to us, really, leaving us at the mercy of tools and systems on which we depend.

Arbesman doesn’t advocate starting, say, Word all over again, much less tearing down our power grid for rebuilding from scratch. His suggestion is instead that we, as a society, work on our curiosity about technology and not settle so readily for “magic” in our day-to-day lives. He says this could help us be more realistic about systemic problems that will inevitably arise with our complex systems. “The need to have a more calm, tinkering approach to technologies is going to be very, very important” Arbesman says, and he says we might try and get over the idea that things should “just work,” and think a little bit more about how.