Ceramide rejuvenates the skin but ages muscle

- In the skin, ceramides hold cells together and prevent water from escaping. Elsewhere in the body, ceramide participates in diverse cellular functions such as inflammation, proliferation, cell growth, and cell death.

- Scientists have found that high levels of ceramides in muscle cells contribute to age-related muscle dysfunction.

- Elderly individuals who are genetically predisposed to have reduced levels of ceramide in muscle are stronger and have better muscle function than those who are not.

Ceramides are all the rage in the skincare and beauty world. These waxy little molecules hold our skin cells together, helping our skin stay youthful and healthy by trapping moisture and repelling damaging toxins. However, ceramide’s anti-aging properties may only be skin deep. According to a new study, an overload of ceramides in muscle cells contributes to age-related dysfunction.

As we get older, our bodies don’t regenerate new muscle tissue very efficiently. Consequently, muscle mass and function start to deteriorate. Exercising can fend off the loss of muscle mass as we get older, but it cannot prevent it entirely. This is because, upon aging, skeletal muscle becomes depleted of muscle stem cells, and the remaining stem cells don’t function as efficiently as they once did.

Various stimuli cause muscle stem cell loss and malfunction, such as inflammatory agents, hormonal changes, and loss of neuromuscular connections. Researchers have developed several pharmacological approaches to counteract these stimuli, such as treatment with sex and growth hormones. However, these interventions have shown only marginal effectiveness. So a team of scientists began exploring alternative avenues of treatment.

Ceramide is a double-edged sword

Ceramides are best known for their use in skin care products. These lipid molecules are found within the outermost layer of the epidermis. They form a waxy mortar between cells that protects against excessive water loss from the body and blocks undesired substances, such as allergens and microbes, from penetrating the body. In fact, developing such a lipid-based barrier was an essential step in the evolution of life on dry land.

Beneath the skin, however, ceramides’ role extends far beyond simply providing structural support. Ceramides participate in diverse cellular functions such as inflammation, proliferation, cell growth, and cell death. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel, a group responsible for the independent review of skincare and cosmetic ingredients, has determined that ceramide is safe if not ingested.

However, previous research has shown that ceramide levels increase as we age and that this rise is associated with age-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Other research has shown that ceramide levels are up-regulated in human muscular dystrophies — a group of genetic diseases that cause progressive weakness and loss of muscle mass — and that blocking ceramide synthesis can alleviate the symptoms of these dystrophies. Therefore, in the current study, the authors hypothesized that blocking ceramide that accumulates during aging could counteract age-related muscle dysfunction.

Ceramides accumulate in skeletal muscle

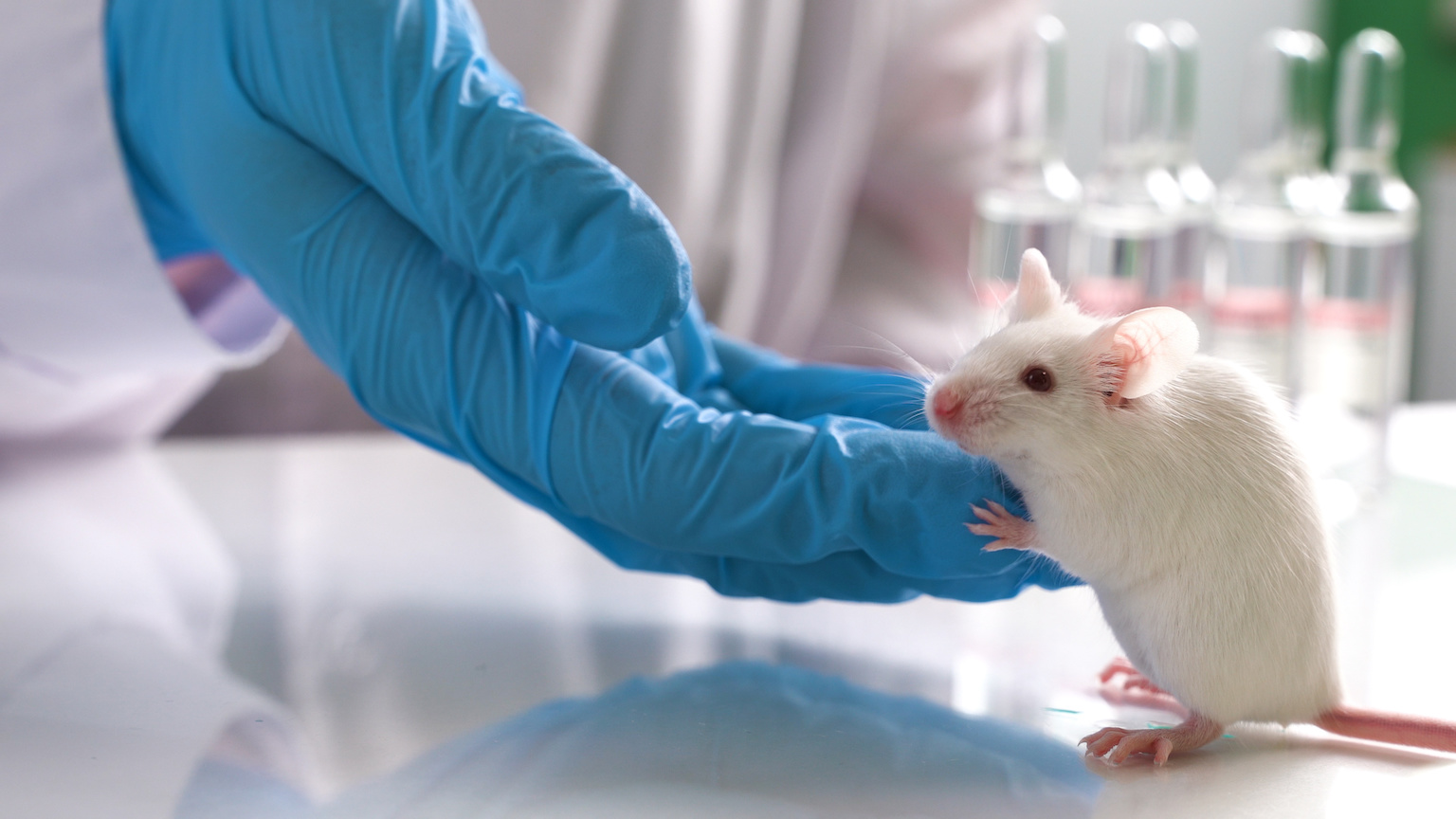

To study how aging affects ceramide production, the researchers compared the total ceramide content in skeletal muscles in young (2-month-old) and aged (2-year-old) mice. They found that the muscles of old mice had higher ceramide levels in skeletal muscle than young mice. The researchers also examined whether reducing ceramide overload could protect against age-related decline in muscle function by treating old mice for six months with ceramide blockers. Indeed, the ceramide blockers prevented loss of muscle mass during aging, made the mice stronger, and allowed them to run longer distances while improving their coordination. Furthermore, they found that ceramide blockers boosted the function of muscle stem cells.

Martin Wohlwend, a co-author of the study, explained, “It turned out that blockade of ceramide production activates muscle stem cells, making muscles build up more protein and shifting fiber type towards fast-twitch glycolytic to produce larger and stronger muscles in aged mice.”

Sphingolipid metabolism in human aging

Finally, the scientists looked at whether reducing ceramides in muscle could also be beneficial in humans. So they examined 2,003 individuals who participated in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study, a Finnish population featuring individuals born in the 1930s and 1940s. These 70-80-year-olds underwent genetic analysis and clinical age-related fitness measurements, including grip strength, arm curls, and walking assessments. The researchers discovered that 25% of the participants had a particular form of a gene that reduces ceramide production in muscle. Interestingly, these individuals were also stronger and able to walk longer, indicating healthier aging, similar to mice treated with ceramide blockers.

“These findings are very important as they provide us with strong incentive to develop inhibitors which could be tested in humans,” says Johan Auwerx, the study’s lead investigator. The scientists are now embarking on collaborations with the pharmaceutical industry.