Study: Re-Framing Climate Change as a Public Health Issue

Changing the conversation about climate change: Graduate students from American and George Mason Universities prepare interview tent on the National Mall.

WASHINGTON, DC — How do Americans respond when they are asked to reflect on the public health risks of climate change and the benefits to health from mitigation-related actions? In other words, if we were to re-frame climate change in terms of localized impacts that people personally experience and can understand–such as vulnerability to extreme heat or poor air quality–could we shift public thinking on the issue? Those are the questions that I examine with Ed Maibach and colleagues in a study published this month at the open access journal BMC Public Health.

We find that even Americans who tend to discount climate change or are ambivalent about its relevance react favorably when the issue is re-framed in the context of public health. Our results suggest that when it comes to public engagement, health experts have an important perspective to share about climate change. This still dramatically under-communicated perspective offers Americans a compelling way to think about an issue that has proven deeply difficult for many people to fully comprehend. The new frame of reference also focuses on a range of possible policy actions that offer local as well as global benefits.Below I provide brief background on the method, the findings, and our conclusions. We encourage readers to review the full open-access study. We wrote the article in a style that was intended to be informative, understandable, and engaging to a broader audience. Later this year, we will be conducting a follow up experimental study that tests the public health frame against a traditional environmental message in the context of a nationally-representative online survey.

Shifting the Train of Thought Towards Public Health

Research over the past several decades has shown that how people “frame” an issue — i.e., how they mentally organize and discuss with others the issue’s central ideas — greatly influences how they understand the nature of the problem, who or what they see as being responsible for the problem, and what they feel should be done to address the problem. Polling data collected by Ed Maibach and colleagues suggest that the dominant mental frame used by most members of the public to organize their conceptions about climate change is that of “climate change as an environmental problem.” However, as I reviewed in a paper published last year and as we discuss in the study:

…when climate change is framed as an environmental problem, this interpretation likely distances many people from the issue and contributes to a lack of serious and sustained public engagement necessary to develop solutions. This focus is also susceptible to a dominant counter frame that the best solution is to continue to grow the economy – paying for adaptive measures in the future when, theoretically, society will be wealthier and better able to afford them – rather than focus on the root causes of the environmental problem. This economic frame likely leaves the public ambivalent about policy action and works to the advantage of industries that are reluctant to reduce their carbon intensity. Indeed, it is precisely the lack of a countervailing populist movement on climate change that has made policy solutions so difficult to enact.

Suggesting a novel frame for climate change — i.e., a frame such as public health that people had not previously considered — is potentially useful when it helps people understand the issue more clearly by providing additional personal and societal relevance. Re-defining climate change in public health terms should help people make connections to already familiar problems such as asthma, allergies, and infectious diseases experienced in their communities, while shifting the visualization of the issue away from remote Arctic regions, and distant peoples and animals. In the process, giving climate change a public health focus suggests that there is a need to both mitigate (i.e. reduce greenhouse gas emissions) and adapt to the problem (i.e. protect communities and people from current and future health related impacts). The frame also presents the opportunity to involve additional trusted communication partners on the issue, notably public health experts and local community leaders.

Evaluating How Americans Respond to Climate Change as a Health Problem

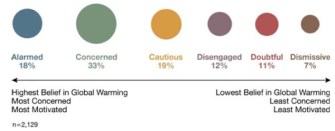

Last summer, joined by outstanding graduate students from AU and GMU, we conducted approximately hour-long open-ended interviews with 70 subjects recruited on the National Mall, at a rural Maryland outlet mall, and over the phone. We were looking for respondents who lived at least 1 hour outside of the Washington, DC area. (In all, our final respondent pool represented 29 states.)Using a short screening survey, we categorized subjects in terms of 6 previously identified audience segments on climate change. These six segments of Americans – the Alarmed (18% of the adult population), the Concerned (33%), the Cautious (19%), the Disengaged (12%), the Doubtful (11%), and the Dismissive (7%) – fall along a continuum from those who are engaged on the issue and looking for ways to take appropriate actions (the Alarmed) to those who actively deny its reality and are looking for ways to oppose societal action (See below and the Six Americas of Global Warming report.)

During the open-ended interview, we asked respondents to articulate in their own words their beliefs, attitudes, emotions, and behavior relative to climate change. At the end of the session, we then re-set the frame of reference on the issue by asking respondents to read a short essay.

My co-author Ed Maibach conducts an interview in the shade of the Hirshhorn sculpture garden on the National Mall.

The one-page essay was organized into four sections: an opening paragraph that introduced the public health frame on climate change (5 total sentences); a paragraph that emphasized how human health will be harmed if action is not taken to stop, limit, and/or protect against global warming (i.e., a description of the threat; 7 sentences); a paragraph that discussed several mitigation-focused policy actions and their human health-related benefits if adopted (4 sentences); and a brief concluding paragraph intended to reinforce the public health frame (2 sentences). (Read the full essay.)When respondents finished the reading, they were asked to describe in an open-ended format their “general reaction to this essay.” For each portion of the essay they marked in green, they were subsequently asked: “What about each of these sentences was especially clear or helpful to you?” For each portion of the essay they marked in pink, they were also asked: “What about each of these sentences was especially confusing or unhelpful to you?”Two graduate student coders were then trained to reliably code each general reaction statement into one of several thematic categories. The coders were also instructed to assess the overall valence of each respondent’s statements – the first of our dependent measures – rating them as: -1 (entirely negative comments); 0 (mixed, including both positive and negative comments); or 1 (entirely positive comments). To code the respondent’s sentence-specific reactions made with the highlighting pens, sentences marked with only green on at least one word were scored +1 (i.e. indicating “especially clear or useful”), sentences marked with only pink on at least one word were scored -1 (i.e. indicating “especially confusing or unhelpful), and sentences with either no highlighting, or both green and pink, were scored 0. Composite scores were created for each of the four sections of the essay – the opening, the threat section, the benefit section, and the conclusion – by summing the sentence-specific scores in the section and dividing by the number of sentences.

Americans Respond Favorably When Climate Change is Framed in Terms of Public Health

Full details on the findings, conclusions, and limitations to the study can found at the open-access BMC Public Health article. Below I highlight several major findings that readers should consider. First , overall, subjects on average reacted positively and favorably to the public health-framed essay. Many of the respondents in all five segments made open-ended comments about the essay that demonstrated a positive engagement with the material. For example, nearly half (44%) of the comments made by the Disengaged segment indicated that the essay reflected their personal point of view, was informative or thought-provoking, or offered valuable prescriptive information on how to take action relative to the climate problem. Similarly, 39% of the comments made by respondents in the Doubtful segment reflected one of these three themes.

In a methodology that advances dial group techniques used by pollsters and marketing researchers, we statistically analyzed the sentence-by-sentence reactions to the essay across audience segments.

Second, as shown above, the ascending sentence-specific evaluations between the opening and concluding sections of the essay, for the sample overall and for all of the segments (excluding the Dismissive), suggest that the value of the public health frame may not be immediate, but rather may manifest more fully after people have had time to consider the evidence, especially when this evidence is presented with specific mitigation-related policy actions that are likely to have human health benefits.Third, all six segments reacted positively to the following statements focusing on specific mitigation-related policy actions that lead to human health benefits:

“Taking actions to limit global warming – by making our energy sources cleaner and our cars and appliances more efficient, by making our cities and towns friendlier to trains, buses, and bikers and walkers, and by improving the quality and safety of our food – will improve the health of almost every American.””Cleaner energy sources and more efficient use of energy will lead to healthier air for children and adults to breathe.””Improving the design of our cities and towns in ways that make it easier to get around on foot, by bike and on mass transit will reduce the number of cars and help people become more physically active, lose weight.”

Fourth, respondents in all segments tended to react negatively to the statement:

“Increasing our consumption of fruits and vegetables, and reducing our intake of meat – especially beef – will help people maintain a healthy weight, will help prevent heart disease and cancer, and will play an important role in limiting global warming.”

From the close to the article emphasizing our take away conclusions:

We believe that the public health community has an important perspective to share about climate change, a perspective that potentially offers the public a more salient way to comprehend an issue that has proven deeply difficult for many people to fully comprehend. Moreover, the public health perspective offers a vision of a better, healthier future – not just a vision of environmental disaster averted, and it focuses on a range of possible policy actions that offer local as well as global benefits. Many leading experts in climate change communication, including the present authors, have suggested that a positive vision for the future and a localization of the issue is precisely what has been missing from the public dialogue on climate change thus far [13,22,32].Not all aspects of the public health implications, however, may be engaging. Certain key recommendations, such as eating less meat, tended to elicit counter-arguments among people in many of the segments in our research. Our research provides clues about specific public health messages that might not be helpful, and suggests the need in future research to look carefully for examples or associations that trigger counter-arguments and negative reactions.There is an urgent need for the public health community to successfully educate the public and policy makers about the serious human health implications of climate change, and to engage those publics in appropriate preventive and adaptive responses. As a point of strategy, however, our findings may suggest that continuing to communicate about the problem of climate change is not likely to generate wider public engagement. Instead public health voices may be wise to focus their communication on the solutions and the many co-benefits that matter most to people.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The study was funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Health Policy Investigators program to E. Maibach and M.C. Nisbet.

ADDITIONAL READING:

Akerlof, K. et al. (2010). Public Perceptions of Climate Change as a Human Health Risk: Surveys of the United States, Canada, and Malta. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7 (6), 2559-2606. (Open Access)

Bruno, M. (2010, March 19). Why Aren’t Climate Scientists Talking about Health Care Reform. Grist magazine.

Cordon, E. (2010, Feb 5). New York Times’ Andrew Revkin, American University’s Matthew Nisbet Urge Better Communication on Climate Change. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. (HTML)

Frumkin, H. & McMichael AJ (2008). Climate change and public health: thinking, acting and communicating. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5):403-410. (PubMed)

Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., and Leiserowitz, A. (2008). Communication and marketing as climate change intervention assets: A public health perspective. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), 488-500. (Link).

Montenegro, M. (2009, May 21). Is There a Better Word for Doom? Six Experts Discuss the Merits of Framing Climate Change. Seed Magazine.

Nisbet, M.C. (2009). Communicating Climate Change: Why Frames Matter to Public Engagement. Environment, 51 (2), 514-518. (HTML).

Nisbet, M.C. & Mooney, C. (2007). Policy Forum: Framing Science. Science, 316, 5821, 56. (PDF)

Nisbet, M.C. & Scheufele, D.A. (2009). What’s Next for Science Communication? Promising Directions and Lingering Distractions. American Journal of Botany, 96 (10), 1767-1778. (PDF)