Exotic animals and their strange relationship with ancient Greeks and Romans

- The ancient Greeks interpreted descriptions of exotic animals as signs pointing to the existence of mythological creatures.

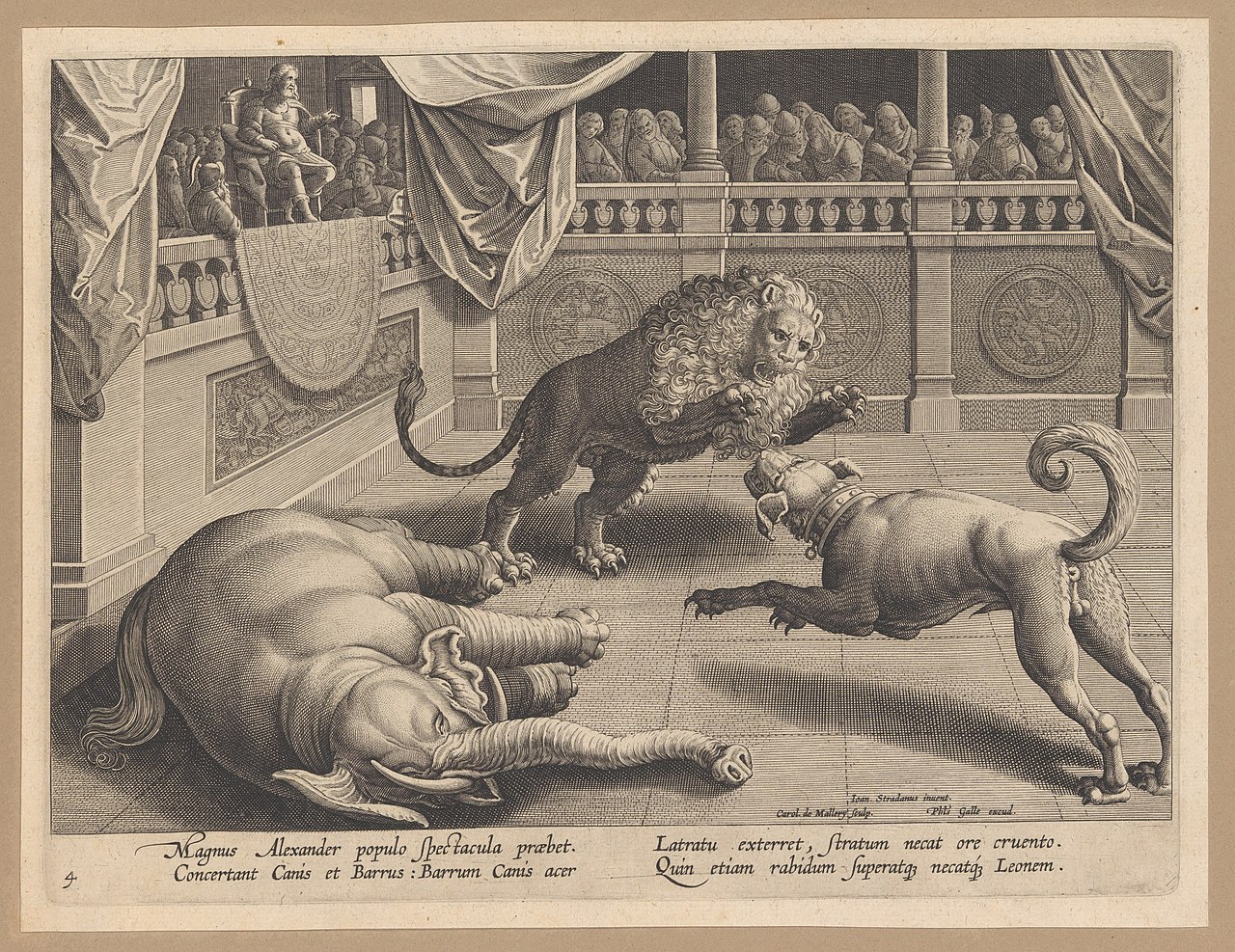

- When specimens of such exotic animals were brought to ancient Rome, they were put on display or made to fight one another inside the Colosseum.

- As the Roman public became more accustomed to these creatures, their perception of them changed drastically.

Driven by the belief that folklore is rooted in reality rather than imagination, the Austrian paleontologist Othenio Abel theorized that the myth of the Cyclops originated from the skulls of the now-extinct pygmy mammoth. According to Abel, the ancient Greeks who once stumbled upon these skulls may well have interpreted their large nasal cavities as eye sockets, which gave rise to the fearsome creature later described in Homer’s Odyssey.

As the historian and ancient folklorist Adrienne Mayor shows in her book The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times, Abel’s hypothesis is most likely incorrect. Still, he was right to assume that people living in classical antiquity interpreted the real world through the colorful lens of mythology and legend. This is especially evident when you look at early depictions of exotic animals that lived far beyond the boundaries of Greece.

Exotic animals in ancient Greece

Take, for instance, this description of a hippopotamus from the Greek historian Herodotus: “The hippopotamus is held sacred in the district of Papremis, but not elsewhere. This animal has four legs, cloven hoofs like an ox, a snub nose, a horse’s mane and tail, conspicuous tusks, a voice like a horse’s neigh, and is about the size of a very large ox. Its hide is so thick and tough that when dried it can be made into spear-shafts.”

Greek authors frequently mentioned exotic animals in the same breath as mythological creatures. Artemidorus, who was born in modern-day Turkey near Lydia, said that elephants in Ethiopia dwelled alongside dragons and sphinxes. And just as Herodotus said that the hide of a hippo can be fashioned into spear-shafts, so too the Greek writer and Cynic philosopher Onesicritus stated that elephants could live for more than half a millennium.

Another noteworthy description comes to us from Ctesias of Cnidus, a Greek physician who spent 17 years in Persia. When Ctesias returned to Greece in 398 BC, he set out two write two books on the East. The first, concerning the history of Persia, was based largely on his own experiences and observations. The second, a book about India which is now mostly lost, was based on the carefully scrutinized accounts of travelers and colleagues Ctesias met abroad.

Among those accounts is one dealing with “wild asses which are as large as horses” and have “a horn on the forehead which is about a foot and a half in length.” Contemporary readers took this passage as proof for the existence of the fabled unicorn, but the American scholar Odell Shepard likened the creature to a “chimera,” a hybrid animal that Ctesias put together in his own mind from descriptions of the Indian rhinoceros, the Tibetan chiru, and the Persian onager.

In Greek mythology, chimeras were fire-breathing monsters that had the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the tail of a serpent. They also serve as a good analogy for how the classical world attempted to make sense of exotic animals. When, in 46 BC, Julius Caesar returned to Rome with a giraffe that he may have received as a parting gift from the Egyptian ruler Cleopatra, fellow Romans dubbed the animal “camelopardalis” or “camelopard” for short.

“This animal,” the historian Dio explained more than a century later, “is like a camel in all respects except that its legs are not all of the same length, the hind legs being the shorter. Beginning from the rump it grows gradually higher, which gives it the appearance of mounting some elevation; and towering high aloft, it supports the rest of its body on its front legs and lifts its neck in turn to an unusual height. Its skin is spotted like a leopard, and for this reason it bears the joint name of both animals.”

Exotic animals in ancient Rome

The Roman Empire stretched from England to Northern Africa and the Middle East. As trade between these regions became more common, so too did the exchange of exotic animals. Romans were exposed to elephants, ostriches, tigers, and lions as early as the 1st century BC. In the next millennium, these were joined by hippos, rhinos, camels, and giraffes. Exotic animals were used in parades, trained to perform tricks, and made to fight.

Inside the Colosseum, animal fights came in two varieties: damnatio ad bestias, in which they devoured convicted criminals as a form of punishment; and venationes, in which they fought other animals or armed gladiators. The venationes were incredibly bloodthirsty, even by Roman standards. Emperor Augustus is said to have killed 3,500 animals during his reign. He was outdone by successors Titus and Trajan, who ordered the deaths of 5,000 and 11,000 animals, respectively.

The Colosseum’s ever-increasing demand for exotic animals sustained specialized hunters living and working on the fringes of the empire. Numerous Roman authors, including Petronius, describe in detail the methods that these professionals used to trace and capture dangerous creatures like bears and tigers without harming them. Their prey were lured in pits where they were left for days or weeks until sufficiently weakened, or captured with nets and tied to wooden boards.

Not all exotic animals were slaughtered by the Romans, especially when they were brought into the capital for the first time in recent memory. Caesar’s giraffe, described by Dio as having been “exhibited to all,” serves as one example. Augustus is thought to have followed suit. “If anything rare and worth seeing was brought to the city,” says the historian Suetonius, “it was his habit to make a special exhibit of it in any convenient place on days when no shows were appointed.”

At the same time, the popularity of any given venatio largely depended on public interest in the participating creatures. The first venatio, according to Pliny the Elder, took place in 252 BC, during the First Punic War. The event featured elephants which Roman forces had captured on the island of Sicily — a novelty at the time. During the final days of the Republic, wealthy patrons exhausted their diplomatic networks to procure the most exotic animals they could find, from leopards to crocodiles.

“While plenty of venationes featured local species like bulls and dogs,” Caroline Wazer, who studied ancient history at the University of Columbia, wrote in The Atlantic, exotic animals “were far more exciting … What’s more, the Romans seem to have had little interest in breeding exotic animals at home. Animals caught in the wild were considered infinitely more dangerous, more valuable, and more fascinating.”

From monsters to fellow organisms

The relationship between Romans and exotic animals is peppered with psychological and sociological complexities. Often, treatment of them came down to individual disposition. Enlightened emperors like Marcus Aurelius had little interest in the Colosseum and its venationes. His successor Commodus, by contrast, was an avid gladiator who reportedly developed a crescent-shaped arrowhead used to decapitate ostriches.

Other rulers, like Caesar and Augustus, teetered between the two extremes. One day, they treated exotic animals with awe and reverence. The next, they relished in organizing a brutal venatio that concluded with their senseless slaughter. A history blog from the University of Chicago seeks answers from Pliny, who said the pursuit of wealth derived from the need to “possess something that might be absolutely destroyed in a moment.” Perhaps the venationes scratched a similar itch.

Venationes weren’t always met with enthusiasm, however. “When [the elephants] had lost all hope of escape,” Pliny recalls a venatio staged by Pompey, “they tried to gain the compassion of the crowd by indescribable gestures of entreaty, deploring their fate with a sort of wailing, so much to the distress of the public that they forgot the general and his munificence carefully devised for their honor, and bursting into tears rose in a body and invoked curses on the head of Pompey.”

“The last day was that of the elephants,” Cicero writes of the same event, “on which there was a great deal of astonishment on the part of the vulgar crowd, but no pleasure whatever. Nay, there was even a certain feeling of compassion aroused by it, and a kind of belief created that that animal has something in common with mankind.” Though the venationes continued long after gladiatorial battles ceased, the practice drew from the Roman public until the very end.

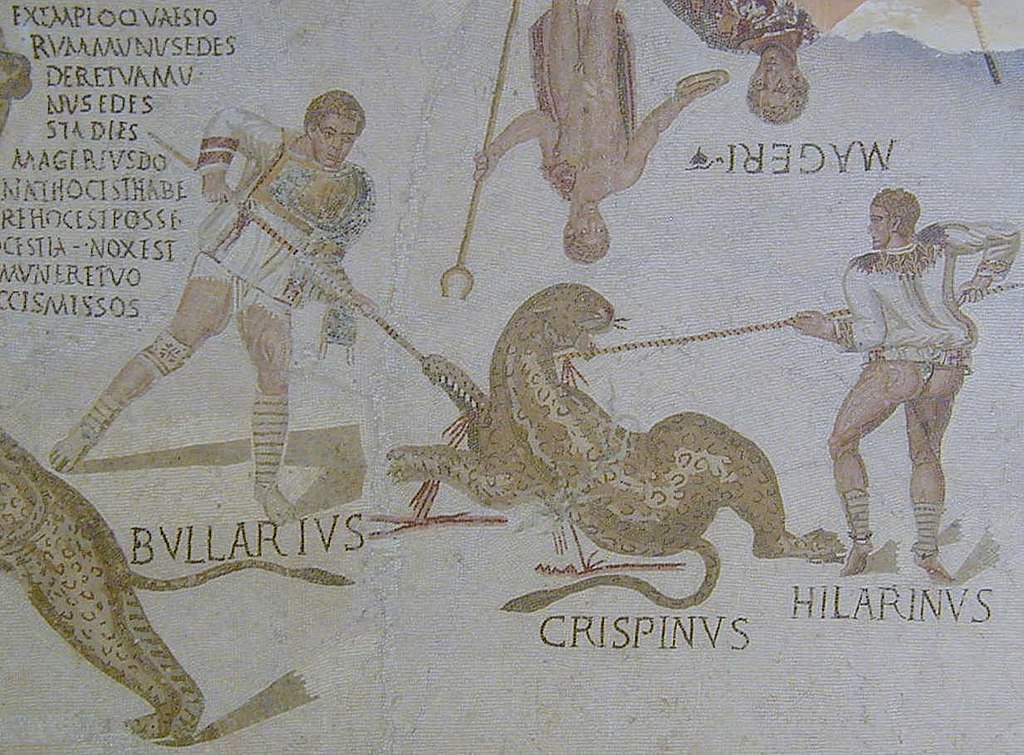

Despite such criticism, the venationes seemed to have played an important role in humanizing exotic animals in Roman times, and turning them from mythological creatures into organisms not dissimilar to humans. In her Atlantic article, Wazer discusses a mosaic in which four leopards fight four gladiators. The leopards were given nicknames, just like their human adversaries, and are depicted as wearing laurel crowns: a sign of exceptional talent and courage.