How Venus flytraps give scientists insights on consciousness and anesthesia

- Over 100 compounds have anesthetic effects on animals and humans, but their mechanisms remain a mystery.

- In the mid-19th century, researchers demonstrated that anesthesia affects plants, suggesting plants and animals must share a biological source of consciousness.

- Anesthesia paralyzes Venus flytrap movements by disrupting electrical signals, similar to its effects on animals and humans.

For much of history, surgery and pain were synonymous. Surgeons prioritized speed over finesse as they pulled, sawed, sliced, sewed, and hammered their poor patients. Then, in 1846, anesthesia arrived. Finally, surgeons could focus on their work without the commotion of a screaming patient. Since then, scientists have identified over a hundred drugs that can anesthetize humans and animals. How these drugs function, however, is still debated among scientists.

Over the last several years, scientists have investigated the mystery of anesthesia from a surprising angle: the Venus flytrap. They have found that anesthesia paralyzes Venus flytraps by disrupting electrical signals, similar to its effects on animals and humans. This suggests plants are ideal subjects for testing anesthetic drugs in future.

Anesthesia blocks consciousness, even in plants

Thirty years after anesthesia debuted in the operating room, Claude Bernard, a French physiologist, demonstrated that the shameplant (Mimosa pudica), which bashfully folds into itself when touched, was unresponsive to touch after exposure to ether, a commonly used anesthetic. The plant also folds into itself at night time, but this movement was not affected by anesthesia. Bernard concluded that anesthesia does not inhibit the ability to move; rather, it inhibits the plant’s ability to sense its environment. That is to say, anesthesia blocks consciousness.

Bernard suggested plants and animals must share a common biological source of consciousness, and this common source must be the target of anesthesia. In animals, the source of consciousness is often considered to be the nervous system. Neurons detect sensory stimuli — such as mechanical pressure from a fly crawling on an arm — and convert it into electrical impulses. Those impulses travel to the brain, which analyzes the impulses and initiates a response, such as shooing the fly away. Plants do not have a nervous system, per se, but they do transmit electrical information in response to environmental stimuli, similar to an animal’s nervous system.

Venus flytraps on anesthesia

Bernard’s research set the stage for anesthesia research during the 20th century, and scientists rushed to uncover how anesthesia disrupts bioelectrical systems, focusing on the complex nervous system of animals. However, progress was slow, and by the early 21st century, scientists found a renewed interest in how anesthesia affects plants, specifically Dionaea muscipula, the Venus flytrap.

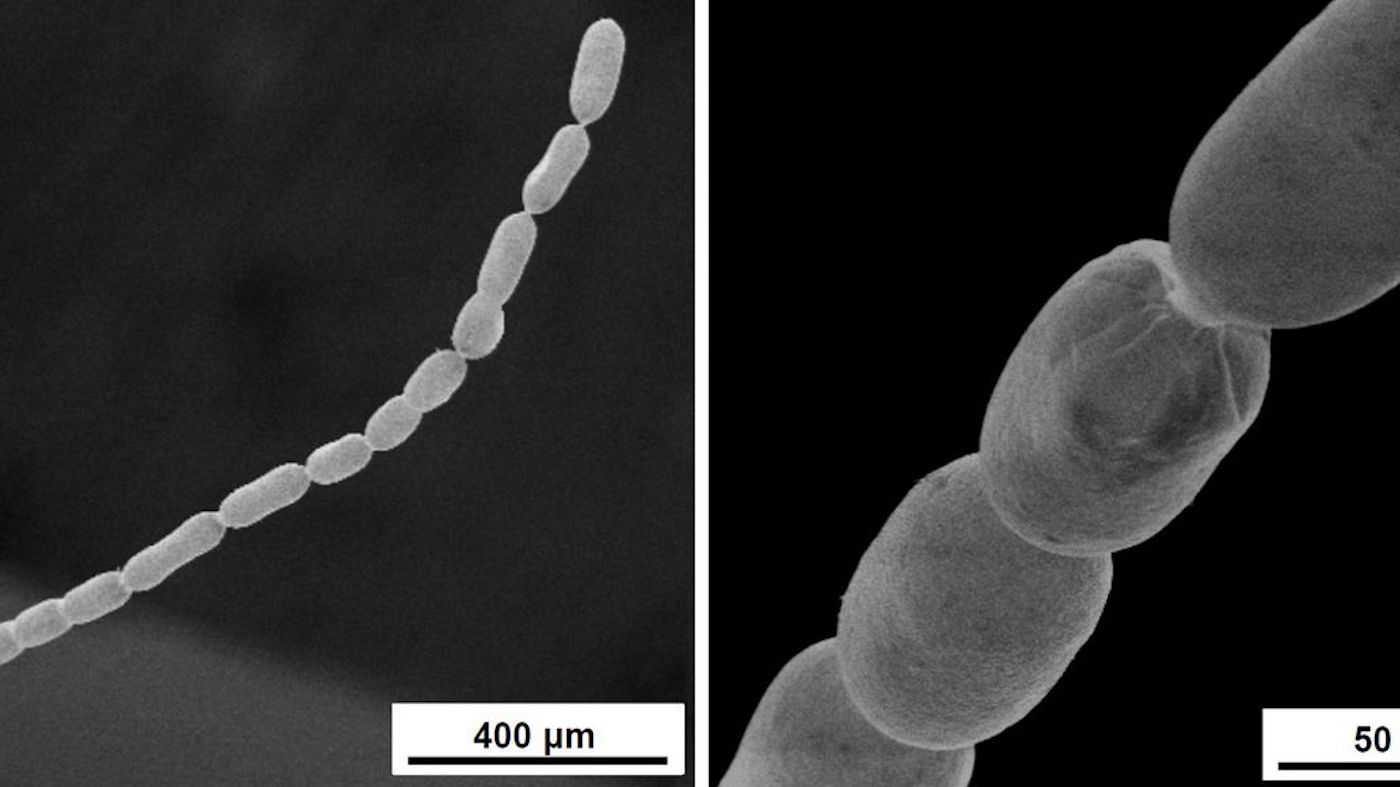

“Unlike most other plants, the Venus flytrap is particularly sensitive to touch. In response to such stimuli, electrical impulses are triggered and transmitted extremely quickly to catch animal prey,” explains Rainer Hedrich, an expert in plant physiology and biophysics. “So it made sense to test whether and [also] how ether affects the carnivorous plant’s sense of touch.”

In 2017, a group of researchers found anesthesia works on Venus flytraps. They sealed a flytrap in a glass chamber with a beaker of ether and, after an hour, stimulated the plant’s sensory hairs, short hair-like structures in the plant’s trap. Normally, this would cause the carnivorous plant to close its trap. Under the effects of anesthesia, there was no movement. However, it was unclear if the lack of movement was because anesthesia blocked the plant’s ability to detect touch or because it blocked the ability to respond to touch. Hedrich suspected it was the latter.

According to Hedrich, Venus flytraps remember when they are touched. When prey lands on the plant’s trap, it brushes against a sensory hair. The hair fires an electrical impulse and releases a wave of signal molecules throughout the trap. After two impulses, the trap closes and imprisons the animal prey. After five impulses, the plant produces digestive enzymes. Because anesthesia disrupts memory in animals, Hedrich hypothesized that anesthesia prevented the plant from remembering each stimulation.

To test this, Hedrich determined if anesthetized flytraps still release signaling molecules. They found that sensory hair still released the signal molecule when stimulated, but the signal did not spread throughout the trap. In an animal, this is similar to local pain receptors detecting pain and releasing local pain signals, but those signals never reaching the brain.

The Venus flytrap’s response to anesthesia suggests that anesthesia affects the plant at cellular and organ levels, similar to animals. And this makes it a model to study general questions related to anesthesia and even consciousness.