Do the laws of physics and neuroscience disprove free will?

- Are we free to make our own choices, or are we automatons controlled by some mysterious conductor?

- Until recently, a debate raged in neuroscience circles concerning this very question because an experiment showed that the brain decides before we are aware of it.

- Fortunately, the experiment was recently debunked, leaving us to face the hard reality that we must be responsible for our actions. Choose wisely.

Are we free to make choices or are we automatons in a giant and invisible cosmic machinery, cogs and wheels turning about, not knowing why we make the choices we make? This is a thorny question that has important consequences, and not just for law enforcement.

Of course, we all want to be free, even if freedom is a very difficult idea to define — firstly because no one is completely free. We all have our professional, family, and social commitments. We grow up within cultural norms. In a sense, to be free is to be able to choose to what we are going to commit. Most people believe that they are free to choose what to do, from the simplest to the more complex: Should I drink coffee with sugar or sweetener? Do I put some money in savings, or do I spend it all? Or, as a friend of mine likes to say, “Should I get married or buy a bicycle?”

The question of free will is essentially a question of agency, of who is in charge as we go through our lives making all sorts of choices. Traditionally, it has been a topic for philosophers and theologians. In the Old Testament, free will became an option after the Fall, when Adam and Even were kicked out of Eden for eating the apple of knowledge. This seems to imply that with knowledge comes the independence to make choices and the freedom to act according to your will. There are good and bad choices, and the bad ones will cost you dearly, if not in this life, then in the afterlife.

Even if you don’t subscribe to this particular narrative, the point is that choices come with consequences. If there is no free will, if we are indeed automatons of sorts, then to what extent are we really choosing when we think we are? And if we are not choosing, what or who is? And if we are not choosing, why do we have this notion or feeling that we are?

A clockwork universe

Early in the 19th century, the idea that the universe was a giant clockwork mechanism was all the rage (at least for the intellectual elite). The French mathematical physicist, Pierre-Simon Laplace, had beautifully refined Newton’s physics to describe, in quantitative detail, the formation of the Solar System and planets and the stability of the planetary orbits around the Sun. They all followed precise quantitative laws that were able to predict when Halley’s comet would return and when and where the next total solar eclipse would occur, among many other astronomical phenomena.

Laplace even speculated that if a super-mind had the power to know the positions and velocities of every particle in the universe at the same moment of time, it would be able to predict the future for all eternity — even the fact that I wanted to write about free will today and that you would be reading this. Legend tells that when Laplace gave a copy of his book Celestial Mechanics to Napoleon, the emperor saluted him on his accomplishment but also asked, “Why is there no God in your cosmos?” Laplace replied, “Because I have no need for this hypothesis.” That is the apex of deterministic reasoning and why people thought free will was a goner. Laplace probably knew, I suspect, that it was all hubris. But it was impressive for sure.

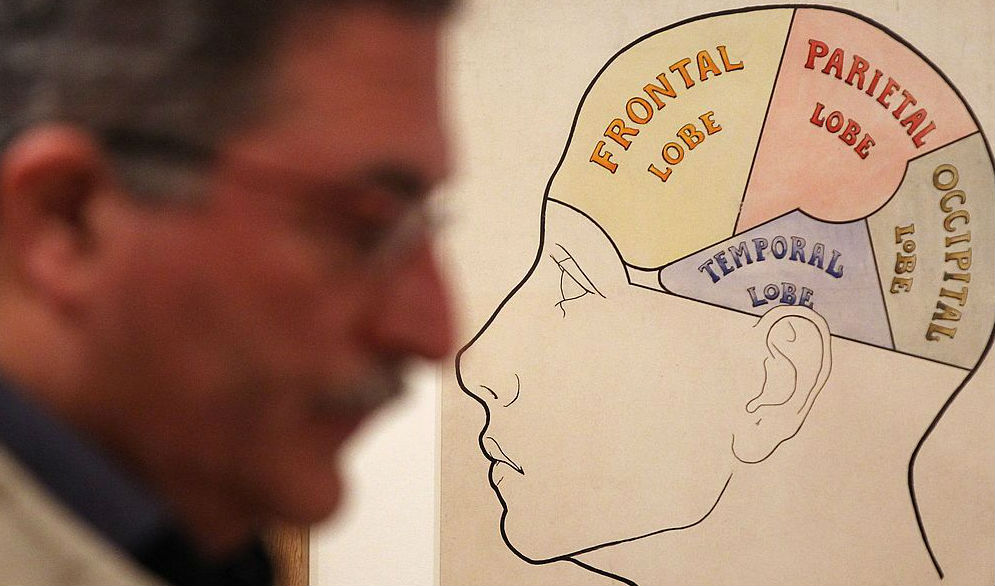

Neuroscience and free will

Fortunately, the mind is not a solar system with strict deterministic laws. We have no clue what kinds of laws it follows, apart from very simplistic empirical laws about nerve impulses and their propagation, which already reveal complex nonlinear dynamics. Still, work in neuroscience has prompted a reconsideration of free will, even to the point of questioning our freedom to choose. Many neuroscientists and some philosophers consider free will to be an illusion. Sam Harris, for example, wrote a short book arguing the case.

This shocking conclusion comes from a series of experiments that revealed something quite remarkable: Our brains decide a course of action before we know it. Benjamin Libet’s pioneering experiments in the 1980s using EEG and more recent ones using fMRI or implants directly into neurons found that the motor region responsible for making a motion in response to a question fired up seven seconds before the subject was aware of it. The brain seems to be deciding before the mind knows about it. But is it really?

The experiment has been debunked, which actually is far from surprising. But what was surprising was the huge amount of noise that the claims against free will emerging from this type of experiment generated. To base the hefty issue of free will on experiments that measure neuronal activity when people move fingers to push a button should hardly count as decisive. Most of the choices we make in life are complex, multi-layered decisions that often take a long time.

Be thankful for free will

This should be a relief to most people, for many reasons. First, we are definitely not automatons without choice. Second, we actually do need to take responsibility for our actions, from wasting water in a long shower to shooting someone dead. There is no cosmic machinery making us do stuff, one way or the other. This means that we must face up to the way we live our lives and how we relate to each other and to the planet, knowing that our choices do have consequences that go beyond our small bubble of being.