We Have Already Entered The Sixth And Final Era Of Our Universe

From the inflationary state that preceded the Big Bang to our cold, lonely, dark energy-dominated fate, the Universe goes through six different eras. We’re living in the last one already.

The Universe is not the same today as it was yesterday. With each moment that goes by, a number of subtle but important changes occur, even if many of them are imperceptible on measurable, human timescales. The Universe is expanding, which means that the distances between the largest cosmic structures are increasing with time.

A second ago, the Universe was slightly smaller; a second from now, the Universe will be slightly larger. But those subtle changes both build up over large, cosmic timescales, and affect more than just distances. As the Universe expands, the relative importance of radiation, matter, neutrinos, and dark energy all change. The temperature of the Universe changes. And what you’d see in the sky would change dramatically as well. All told, there are six different eras we can break the Universe into, and we’re already in the final one.

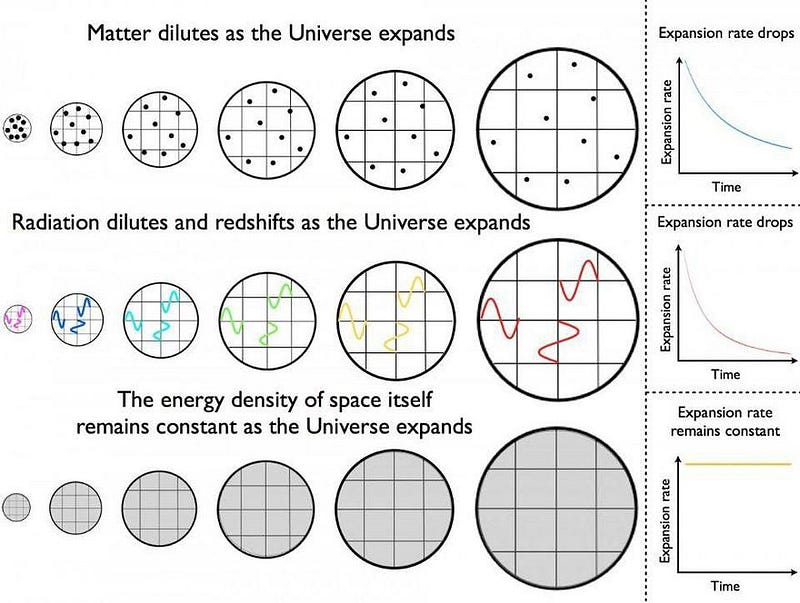

The reason for this can be understood from the graph above. Everything that exists in our Universe has a certain amount of energy in it: matter, radiation, dark energy, etc. As the Universe expands, the volume that these forms of energy occupy changes, and each one will have its energy density evolve differently. In particular, if we define the observable horizon by the variable a, then:

- matter will have its energy density evolve as 1/a³, since (for matter) density is just mass over volume, and mass can easily be converted to energy via E = mc²,

- radiation will have its energy density evolve as 1/a⁴, since (for radiation) the number density is the number of particles divided by volume, and the energy of each individual photon stretches as the Universe expands, adding an additional factor of 1/a relative to matter,

- and dark energy is a property of space itself, so its energy density remains constant (1/a⁰), irrespective of the Universe’s expansion or volume.

A Universe that has been around longer, therefore, will have expanded more. It will be cooler in the future and was hotter in the past; it was gravitationally more uniform in the past and is clumpier now; it was smaller in the past and will be much, much larger in the future.

By applying the laws of physics to the Universe, and comparing the possible solutions with the observations and measurements we’ve obtained, we can determine both where we came from and where we’re headed. We can extrapolate our past history all the way back to the beginning of the hot Big Bang and even before, to a period of cosmic inflation. We can extrapolate our current Universe into the far distant future as well, and foresee the ultimate fate that awaits everything that exists.

When we draw the dividing lines based on how the Universe behaves, we find that there are six different eras that will come to pass.

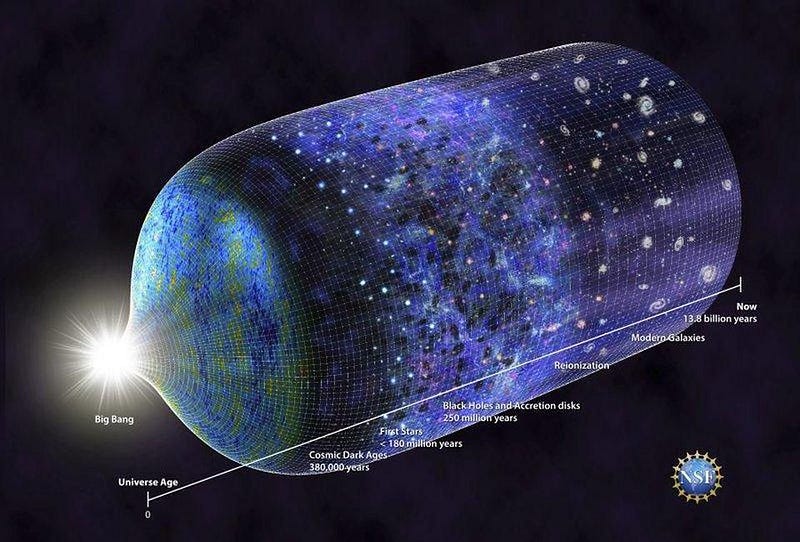

- Inflationary era: which preceded and set up the hot Big Bang.

- Primordial Soup era: from the start of the hot Big Bang until the final transformative nuclear & particle interactions occur in the early Universe.

- Plasma era: from the end of non-scattering nuclear and particle interactions until the Universe cools enough to stably form neutral matter.

- Dark Ages era: from the formation of neutral matter until the first stars and galaxies reionize the intergalactic medium of the Universe completely.

- Stellar era: from the end of reionization until the gravity-driven formation and growth of large-scale structure ceases, when the dark energy density dominates over the matter density.

- Dark Energy era: the final stage of our Universe, where the expansion accelerates and disconnected objects speed irrevocably and irreversibly away from one another.

We already entered this final era billions of years ago. Most of the important events that will define our Universe’s history have already occurred.

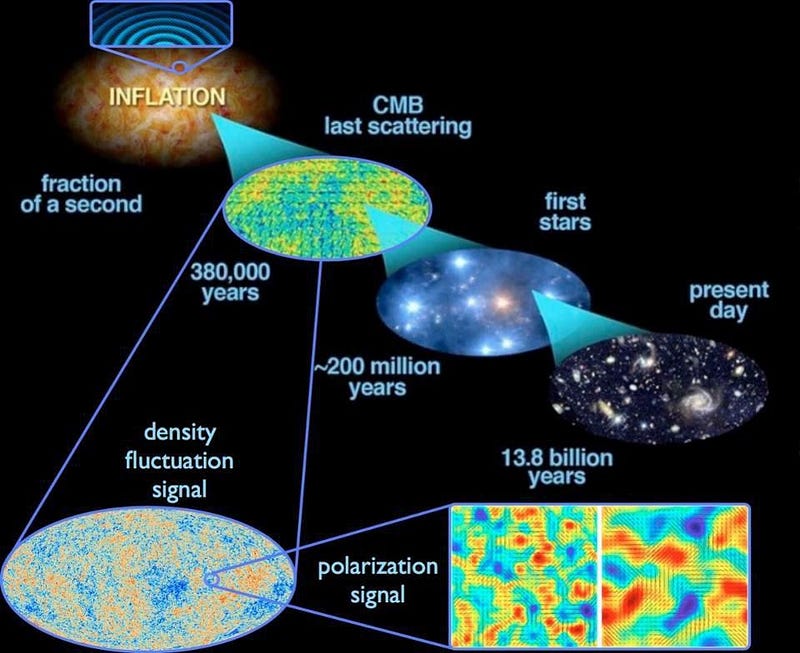

1.) Inflationary era. Prior to the hot Big Bang, the Universe wasn’t filled with matter, antimatter, dark matter or radiation. It wasn’t filled with particles of any type. Instead, it was filled with a form of energy inherent to space itself: a form of energy that caused the Universe to expand both extremely rapidly and relentlessly, in an exponential fashion.

- It stretched the Universe, from whatever geometry it once had, into a state indistinguishable from spatially flat.

- It expanded a small, causally connected patch of the Universe to one much larger than our presently visible Universe: larger than the current causal horizon.

- It took any particles that may have been present and expanded the Universe so rapidly that none of them are left inside a region the size of our visible Universe.

- And the quantum fluctuations that occurred during inflation created the seeds of structure that gave rise to our vast cosmic web today.

And then, abruptly, some 13.8 billion years ago, inflation ended. All of that energy, once inherent to space itself, got converted into particles, antiparticles, and radiation. With this transition, the inflationary era ended, and the hot Big Bang began.

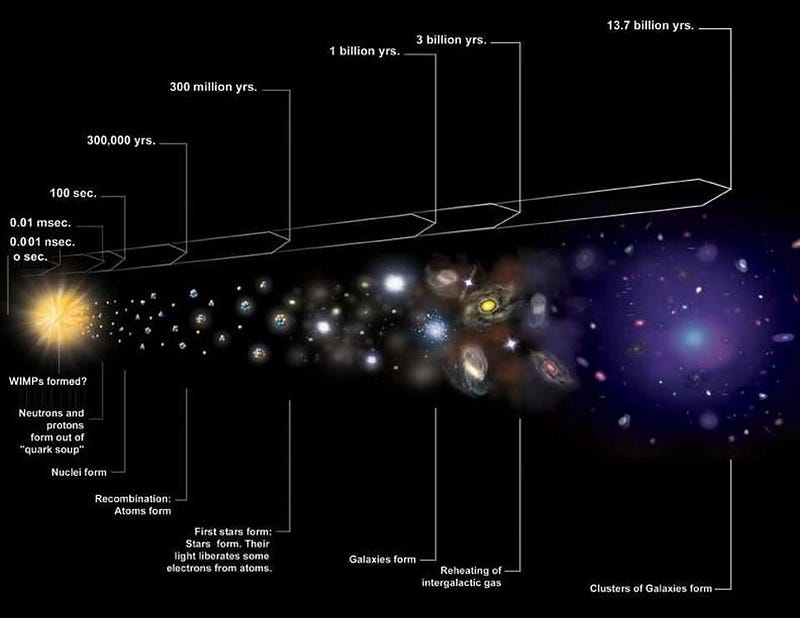

2.) Primordial Soup era. Once the expanding Universe is filled with matter, antimatter and radiation, it’s going to cool. Whenever particles collide, they’ll produce whatever particle-antiparticle pairs are allowed by the laws of physics. The primary restriction comes only from the energies of the collisions involved, as the production is governed by E = mc².

As the Universe cools, the energy drops, and it becomes harder and harder to create more massive particle-antiparticle pairs, but annihilations and other particle reactions continue unabated. 1-to-3 seconds after the Big Bang, the antimatter is all gone, leaving only matter behind. 3-to-4 minutes after the Big Bang, stable deuterium can form, and nucleosynthesis of the light elements occurs. And after some radioactive decays and a few final nuclear reactions, all we have left is a hot (but cooling) ionized plasma consisting of photons, neutrinos, atomic nuclei and electrons.

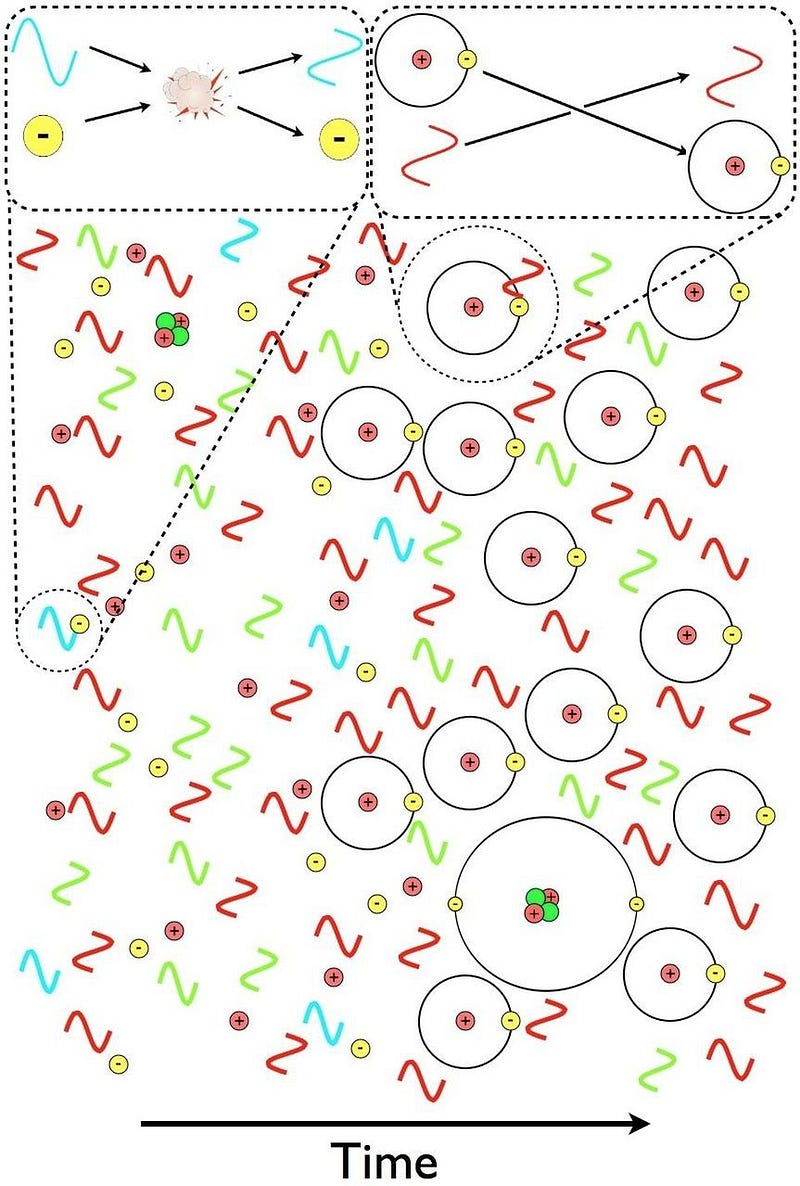

3.) Plasma era. Once those light nuclei form, they’re the only positively (electrically) charged objects in the Universe, and they’re everywhere. Of course, they’re balanced by an equal amount of negative charge in the form of electrons. Nuclei and electrons form atoms, and so it might seem only natural that these two species of particle would find one another immediately, forming atoms and paving the way for stars.

Unfortunately for them, they’re vastly outnumbered — by more than a billion to one — by photons. Every time an electron and a nucleus bind together, a high-enough energy photon comes along and blasts them apart. It isn’t until the Universe cools dramatically, from billions of degrees to just thousands of degrees, that neutral atoms can finally form. (And even then, it’s only possible because of a special atomic transition.)

At the beginning of the Plasma era, the Universe’s energy content is dominated by radiation. By the end, it’s dominated by normal and dark matter. This third phase takes us to 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

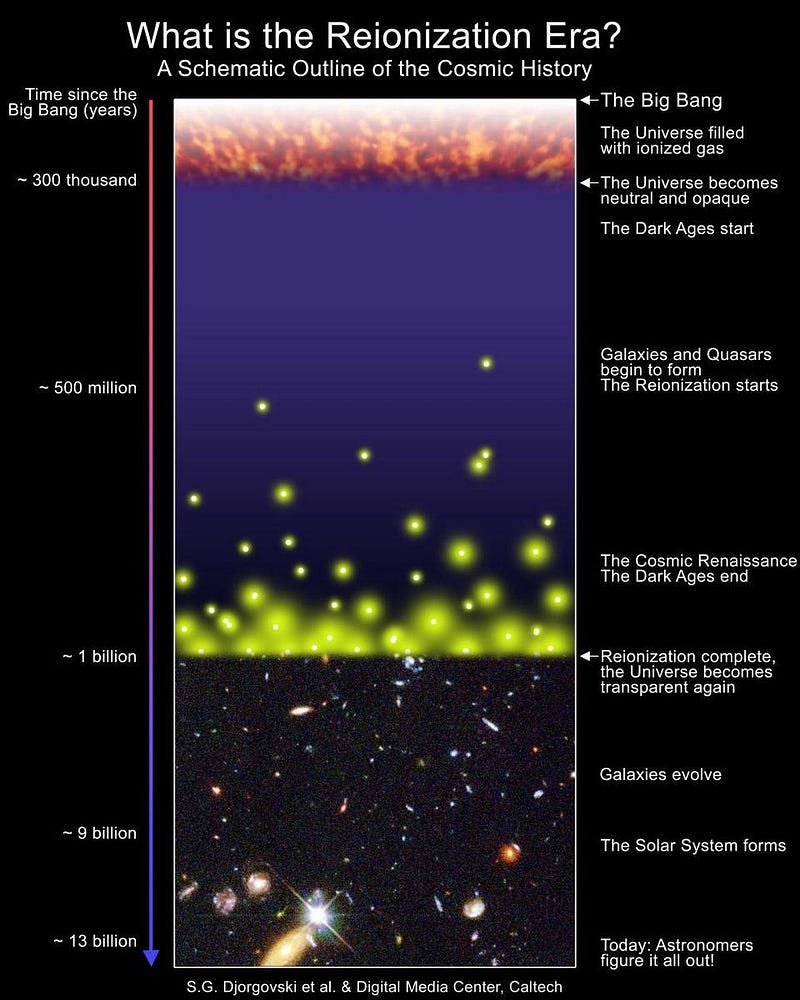

4.) Dark Ages era. Filled with neutral atoms, at last, gravitation can begin the process of forming structure in the Universe. But with all these neutral atoms around, what we presently know as visible light would be invisible all throughout the sky.

Why’s that? Because neutral atoms, particularly in the form of cosmic dust, are outstanding at blocking visible light.

In order to end these dark ages, the intergalactic medium needs to be reionized. That requires enormous amounts of star-formation and tremendous numbers of ultraviolet photons, and that requires time, gravitation, and the start of the cosmic web. The first major regions of reionization take place 200–250 million years after the Big Bang, but reionization doesn’t complete, on average, until the Universe is 550 million years old. At this point, the star-formation rate is still increasing, and the first massive galaxy clusters are just beginning to form.

5.) Stellar era. Once the dark ages are over, the Universe is now transparent to starlight. The great recesses of the cosmos are now accessible, with stars, star clusters, galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the great, growing cosmic web all waiting to be discovered. The Universe is dominated, energy-wise, by dark matter and normal matter, and the gravitationally bound structures continue to grow larger and larger.

The star-formation rate rises and rises, peaking about 3 billion years after the Big Bang. At this point, new galaxies continue to form, existing galaxies continue to grow and merge, and galaxy clusters attract more and more matter into them. But the amount of free gas within galaxies begins to drop, as the enormous amounts of star-formation have used up a large amount of it. Slowly but steadily, the star-formation rate drops.

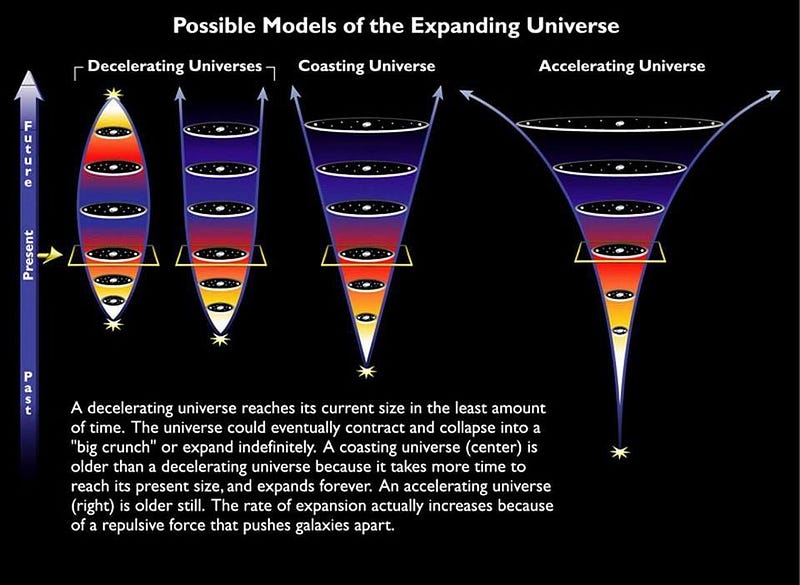

As time goes forward, the stellar death rate will outpace the birth rate, a fact made worse by the following surprise: as the matter density drops with the expanding Universe, a new form of energy — dark energy — begins to appear and dominate. 7.8 billion years after the Big Bang, distant galaxies stop slowing down in their recession from one another, and begin speeding up again. The accelerating Universe is upon us. A little bit later, 9.2 billion years after the Big Bang, dark energy becomes the dominant component of energy in the Universe. At this point, we enter the final era.

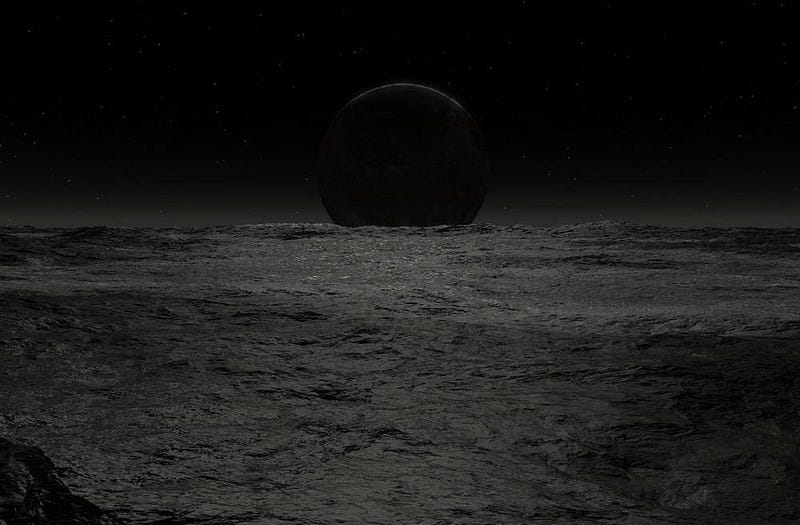

6.) Dark Energy age. Once dark energy takes over, something bizarre happens: the large-scale structure in the Universe ceases to grow. The objects that were gravitationally bound to one another before dark energy’s takeover will remain bound, but those that were not yet bound by the onset of the dark energy age will never become bound. Instead, they will simply accelerate away from one another, leading lonely existences in the great expanse of nothingness.

The individual bound structures, like galaxies and groups/clusters of galaxies, will eventually merge to form one giant elliptical galaxy. The existing stars will die; new star formation will slow down to a trickle and then stop; gravitational interactions will eject most of the stars into the intergalactic abyss. Planets will spiral into their parent stars or stellar remnants, owing to decay by gravitational radiation. Even black holes, with extraordinarily long lifetimes, will eventually decay from Hawking radiation.

In the end, only black dwarf stars and isolated masses too small to ignite nuclear fusion will remain, sparsely populated and disconnected from one another in this empty, ever-expanding cosmos. These final-state corpses will exist even googols of years onward, continuing to persist as dark energy remains the dominant factor in our Universe.

This last era, of dark energy domination, has already begun. Dark energy became important for the Universe’s expansion 6 billion years ago, and began dominating the Universe’s energy content around the time our Sun and Solar System were being born. The Universe may have six unique stages, but for the entirety of Earth’s history, we’ve already been in the final one. Take a good look at the Universe around us. It will never be this rich — or this easy to access — ever again.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.