How the anthropic principle became the most abused idea in science

There’s useful science to be gotten out of it, but most science that mentions it is anything but.

“There is a voice inside of you

That whispers all day long,

‘I feel this is right for me,

I know that this is wrong.’” –Shel Silverstein

The Universe has the fundamental laws that we observe it to have. Also, we exist, and are made of the things we’re made of, obeying those same fundamental laws. And therefore, we can construct two very simple statements that would be very difficult to argue against:

- We must be prepared to take account of the fact that our location in the Universe is necessarily privileged to the extent of being compatible with our existence as observers.

- The Universe (and hence the fundamental parameters on which it depends) must be as to admit the creation of observers within it at some stage.

These two statements, spoken first by physicist Brandon Carter in 1973, are known, respectively, as the Weak Anthropic Principle and the Strong Anthropic Principle. They simply note that we exist within this Universe, which has the fundamental parameters, constants and laws that it has. And our existence is proof enough that the Universe allows for creatures like us to come into existence within it.

These simple, self-evident facts actually carry a lot of weight. It tells us that our Universe does exist with such properties that an intelligent observer could possibly have evolved within it. This stands starkly in contrast to properties that are incompatible with intelligent life, which cannot describe our Universe, on the grounds that no one would ever exist to observe it. That we are here to observe the Universe — that we actively engage in the act of observing — implies that the Universe is wired in such a way to admit our existence. This is the essence of the Anthropic Principle.

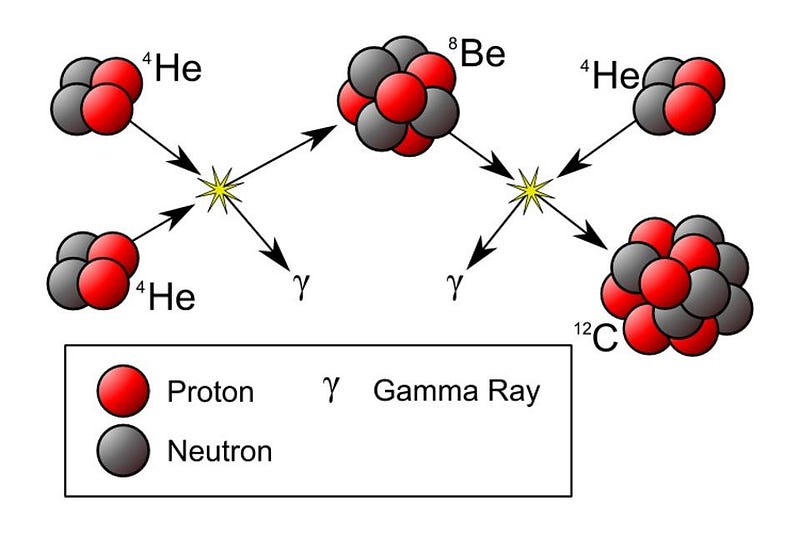

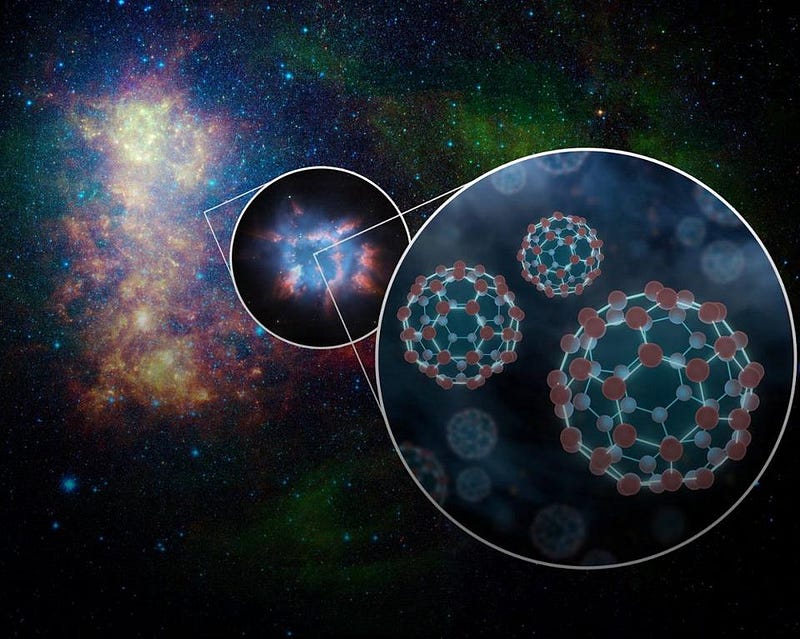

It enables us to make a number of legitimate, scientific statements and predictions about the Universe as well. The fact that we are observers made of carbon tells us that the Universe must have created carbon in some fashion, and led Fred Hoyle to predict that an excited state of the carbon-12 nucleus must exist at a particular energy so that three helium-4 nuclei could fuse into carbon-12 in the interior of stars. Five years later, the discovery of both the theoretical Hoyle State and the mechanism for forming it — the triple-alpha process — was discovered and confirmed by nuclear physicist Willie Fowler, leading to an understanding of how the heavy elements in the Universe were built up in stars throughout the Universe’s history.

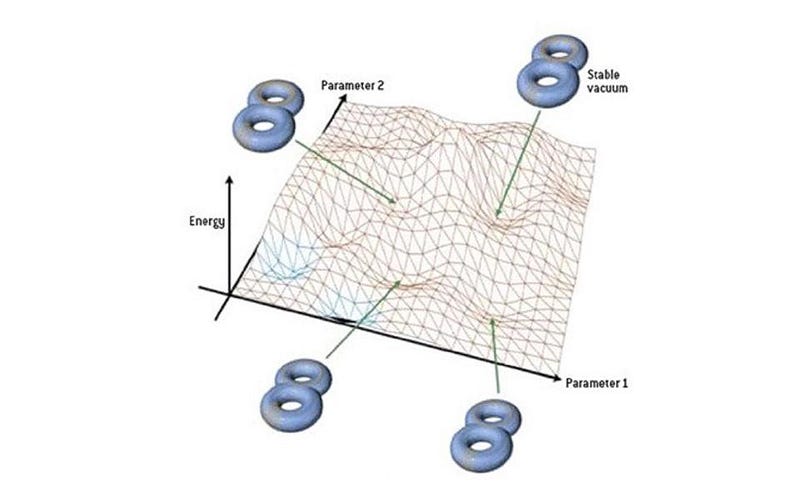

Calculating what the value of our Universe’s vacuum energy — the energy inherent to empty space itself — should be from quantum field theory gives an absurd value that’s far too high. The energy of empty space determines how quickly the Universe’s expansion rate grows (or its contraction rate grows, if it’s negative); if it were too high, we never could have formed life, planets, stars or even molecules and atoms themselves. Given that the Universe arose with galaxies, stars, planets and human beings on it, the value of the Universe’s vacuum energy, Steven Weinberg calculated in 1987, must be no higher than 10^-118 times the number our naïve calculations give us. When we discovered dark energy in 1998, we actually measured that number for the first time, and concluded it was 10^-120 times the naïve prediction. The anthropic principle guided us where our calculational power had failed.

Yet the original two surprisingly simple statements, the Weak and Strong Anthropic Principles, have been misinterpreted so thoroughly that now they’re routinely used to justify illogical, non-scientific statements. People claim that the anthropic principle supports a multiverse; that the anthropic principle provides evidence for the string landscape; that the anthropic principle requires we have a large gas giant to protect us from asteroids; that the anthropic principle explains why we’re located at the distance we are from the galactic center. In other words, people use the anthropic principle to argue that the Universe must be exactly as it is because we exist the way we do. And that’s not only untrue, it’s not even what the anthropic principle says.

The anthropic principle simply says that we, observers, exist. And that we exist in this Universe, and therefore the Universe exists in a way that it allows observers to come into existence. If you set up the laws of physics so that the existence of observers is impossible, what you’ve set up clearly doesn’t describe our Universe. The evidence for our existence means the Universe allows our existence, but it doesn’t mean the Universe must have unfolded exactly this way. It doesn’t mean our existence is mandatory. And it doesn’t mean the Universe must have given rise to us exactly as we are. In other words, you cannot say “the Universe must be the way it is because we’re here.” That’s not anthropics at all; that’s a logical fallacy. So how did we wind up here?

In 1986, John Barrow and Frank Tipler wrote an influential book, The Anthropic Cosmological Principle, where they redefined the principles. They stated:

- The observed values of all physical and cosmological quantities are not equally probably but they take on values restricted by the requirement that there exists sites where carbon-based life can evolve and by the requirement that the Universe be old enough for it to have already done so.

- The Universe must have those properties which allow life to develop within it at some stage in history.

So instead of “our existence as observers means that the laws of the Universe must be such that the existence of observers is possible,” we get “the Universe must allow carbon-based, intelligent life and that Universes were life doesn’t develop within it are disallowed.” Barrow and Tipler go further, and offer alternative interpretations, including:

- The Universe, as it exists, was designed with the goal of generating and sustaining observers.

- Observers are necessary to bring the Universe into being.

- An ensemble of Universes with different fundamental laws and constants are necessary for our Universe to exist.

If that last one sounds a lot like a bad interpretation of the multiverse, it’s because all of Barrow and Tipler’s scenarios are based on bad interpretations of a self-evident principle!

It’s true that we do exist in this Universe, and that the laws of nature are what they are. By looking at what unknowns might be constrained by the fact of our existence, we can learn something about our Universe. In that sense, the anthropic principle has scientific value! But if you start speculating about what the relationship between humanity, observers or other post hoc ergo propter hoc arguments, you are missing out on your opportunity to actually understand the Universe. Don’t fall for bad anthropic arguments; the fact that we’re here can’t tell us why the Universe is this way and not any other. But if you want to better predict the parameters in the Universe we actually have, the fact that we exist can guide you to a solution you might not have arrived at by any other means.

Thanks to Geraint Lewis and Luke Barnes for bringing to light much of this information in their thought-provoking book, A Fortunate Universe, now available worldwide.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!