Supermoon: Fact vs. Fiction

We’ve just had the largest full Moon in 68 years. Here’s what was — and wasn’t — true.

“For most people, we often marvel at the beauty of a sunrise or the magnificence of a full moon, but it is impossible to fathom the magnitude of the universe that surrounds us.” –Richard H. Baker

This Nov. 14, the full Moon will light up the night sky, brighter and larger than it’s been at any time as viewed from Earth since 1948. This most super of Supermoons is a sight to behold, but fortunately an easy one for anyone with clear, cloudless skies. The science behind it is simple and compelling, but there’s also a tremendous amount of misinformation out there about it. Let’s help you separate fact from fiction about the Supermoon, and just maybe the extra knowledge will help you enjoy it all that much more.

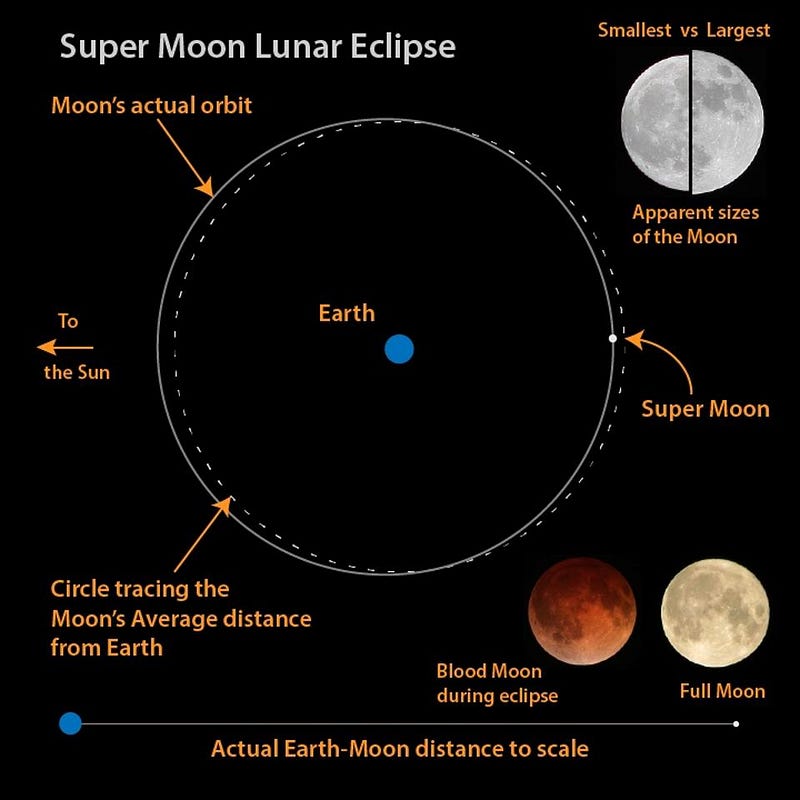

Fact: A Supermoon occurs because the Moon moves in an ellipse, not a circle, around the Earth. At its closest, or perigee, the Moon can get as close as 356,375 km to Earth, which is more than 50,000 km closer than its farthest (apogee) point, which can be as far as 406,720 km away. As the Earth orbits the Sun, the ellipse barely rotates at all, meaning that we get a full Moon closest to perigee every 14 months. The full Moons on either side of that closest Supermoon are usually also close enough thatwe normally see three Supermoons in a row.

Fiction: The Nov. 14 Supermoon is when perigee and maximum fullness align perfectly. It comes really, really close, but closest approach (perigee) and the phase of maximum fullness are still offset by approximately 90 minutes. North American viewers will want to view the full Moon just before sunrise on Monday, the 14th, to catch it at its biggest and brightest.

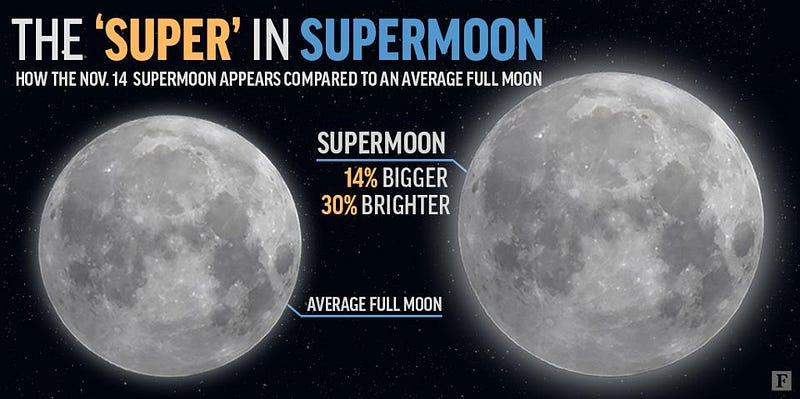

Fact: This full Moon is 14% closer and 30% brighter than the smallest, most distant full Moons of the year. While the full Moon is always the brightest thing in the night sky, an amateur observer who goes out even just a few times a year can teach themselves to spot the difference. Keep an eye out for this full Moon and then the ones that occur next year in late spring/early summer, and you might be able to see it for yourself!

Fiction: This Supermoon is the closest full Moon we’ll have in our lifetimes. For those of us who were around in 1948, that’s clearly not true, but we don’t have to wait another 68 years to have a closer one. That’s coming up on Nov. 25, 2034, just 18 years from now! The distance that full Moon will achieve, 356,448 km, is just 0.017% closer than the 356,509 km we’ll see with this year’s closest Supermoon approach. For those of us who make it to Dec. 6, 2052, that full Moon will be the closest of the century: 356,421 km from Earth.

Fact: The closest perigee full Moon always comes just two weeks, either before or after, the farthest apogee new Moon! This year, it occurred on Halloween: Oct. 31, 2016, when the Moon reached a distance of 406,662 km, just 58 km short of its maximum distance.

Fiction: The tides will be significantly larger than normal. Although it’s true that the tidal forces will be slightly greater, they’re only 2% larger than last month’s full Moon. That means that if last month, there was a three foot (~1 meter) difference between high tide and low tide, there will be an extra 3/4ths-of-an-inch (2 cm) difference; not even discernible without a measuring device.

Fact: The biggest factor in the tides being large is because the Sun, Earth and Moon are almost in perfect alignment: spring tides. But this isn’t special to a full Moon or a Supermoon; this happens during every full Moon and every new Moon. The smallest tides (neap tides) occur when the Moon is half full and the Sun, Earth and Moon make a 90º angle with respect to one another.

Fiction: A perigee Supermoon results in a total lunar eclipse. The Moon is inclined to the Earth-Sun plane at 5º, but only takes up 0.5º on the sky. It’s only about once a year on average (although they’re clustered) that we get a total lunar eclipse, and the next one will occur on Jan. 31, 2018. That’s actually the one you want to look for to see the largest tides; perigee occurs just one day before: Jan. 30, 2018.

Fact: November’s full Moon is known as a Beaver Moon. Why? Because this was the perfect time of year to set beaver traps. Every full Moon has a historic name related to activities or animals that were essential at that particular time of year, like Harvest Moon, Wolf Moon, Buck Moon and Sturgeon Moon.

Fiction: Supermoons affect a woman’s natural menstrual cycle. Sorry folks; this one’s just an urban legend. Most women have cycles that repeat every 27 to 33 days, and the lunar cycle takes 29.5 days from full Moon to full Moon. Unless you happen to have a cycle that coincides with that exactly, everything else that people see is simply our own minds putting it there.

No matter what, a big, bright full Moon is an incredible experience, and this is the best one we’re going to get for decades in either directions. So go out and enjoy it, and may your experience be all the richer for knowing the facts from the fiction!

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!