Was Earth born with life already on it?

Rather than life arising on Earth, did it already exist in space prior to our planet’s formation?

“When you arise in the morning, think of what a precious privilege it is to be alive — to breathe, to think, to enjoy, to love.” –Marcus Aurelius

If you asked a professional — a biologist, a fossil-hunter or a geologist — how old life on Earth was back in the 1970s, you would’ve gotten a very careful “I don’t know” answer. Going back before the rise of mammals, before birds, dinosaurs, reptiles, fish, crustaceans or even starfish and jellyfish — before the Cambrian explosion some 500–600 million years ago — we knew that Earth was inhabited. We knew we were a living planet, but the evidence was very scarce. While the past half-a-billion years or so provides a very rich fossil record, the way fossils form has an inherent limit to how far back we can see. Normally, animal corpses can get covered over by water, and by dirt deposits atop that water, creating the fossil record that we know, examine and study.

That’s sedimentary rock: the kind that contains fossils. But place too many layers of rock atop your fossils for too long, and that combination of pressure and time will cause changes in that rock, and result in a metamorphosing of its contents. Rock that begins to metamorphose can still contain fossils so long as it’s only partially metamorphosed. But completely metamorphosed rock no longer has any. So if you asked a scientist who studied Earth’s natural history some 40 years ago how old life on Earth was, they would’ve told you at least one-to-two billion years and probably more, but they couldn’t prove it.

After all, it’s not like you can just go back in time and look at what was present then; the only evidence we have is the little bits and pieces that survive from back then, and almost all of what survives has changed over that time.

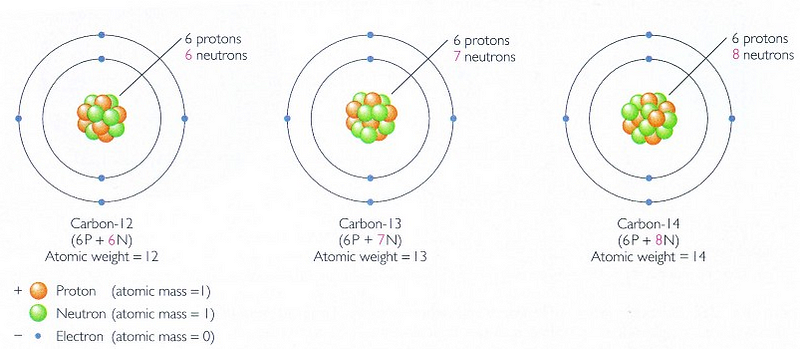

But in the decades since, we realized something: even though the fossils themselves may no longer be discernible to us today, the remnants of organic matter leave a particular signature in the form of carbon. You may be used to “carbon dating” in the form of measuring the carbon-14 to carbon-12 ratio in organisms, since both forms of carbon are absorbed into organic matter, with carbon-14 being created in the upper atmosphere by cosmic rays and decaying with a half-life of around 5,700 years. As long as you’re alive, you breathe in and ingest both forms of carbon; when you decompose, the carbon-14 decays and isn’t replaced by any new carbon-14. Hence, if you can measure the carbon-14 to carbon-12 ratio (carbon dating), you can know roughly, with an error of a few thousand years, how long ago a particular organism died.

This can only take you back around a hundred thousand years or so before the carbon-14 content gets too low to be effective. But there’s another form of carbon we don’t talk about in the same breath: carbon-13, which, like carbon-12, is stable, and which is about 1.1% as abundant as the other forms of carbon.

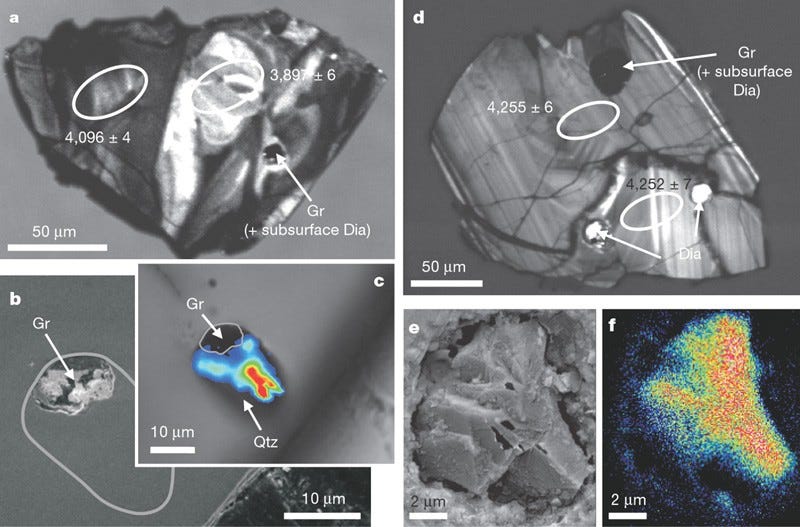

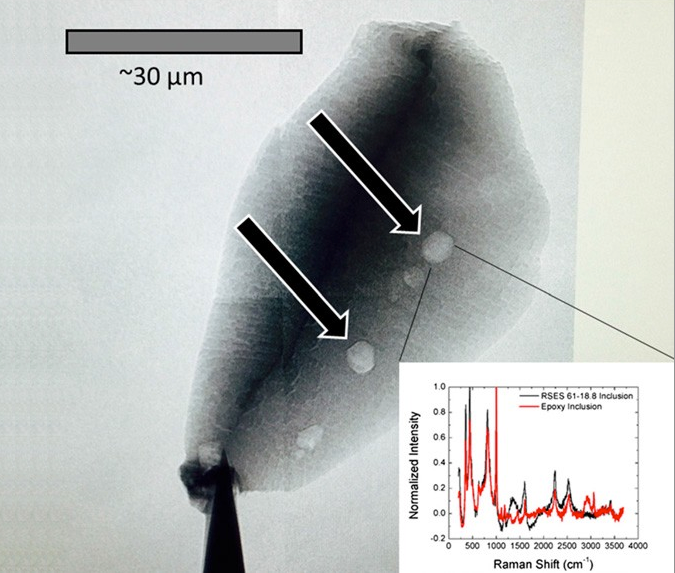

Living organisms — as far as we’ve been able to biologically observe — seem to prefer to uptake carbon-12 to carbon-13, due to metabolic enzymes reacting with carbon-12 more efficiently. If you find an ancient source of carbon and it’s enhanced with carbon-12 as opposed to carbon-13, that’s a good indicator that it’s the remnants of an organic life-form. By looking for graphite, a form of pure carbon, deposited in otherwise highly metamorphosed rocks (things like zircons), we’ve been able to push back well beyond that 1–2 billion year barrier, and had placed the emergence of Earth-life all the way back to 3.8 billion years ago, or just some 750 million years after Earth formed. But as of 2015, we’ve done even better.

By finding graphite deposits in zircons that are 4.1 billion years old, graphite deposits that show this carbon-12 enhancement, we now have evidence that life on Earth goes back at least 90% of Earth’s history, and possibly even longer! After all, finding the remnants of organic matter in a certain location means the organic matter is at least as old as the location it’s buried in, but it could still be even older. This is so early that it might make you think that perhaps this life didn’t originate here on Earth, but that Earth was born with life. And this could really, truly be the case.

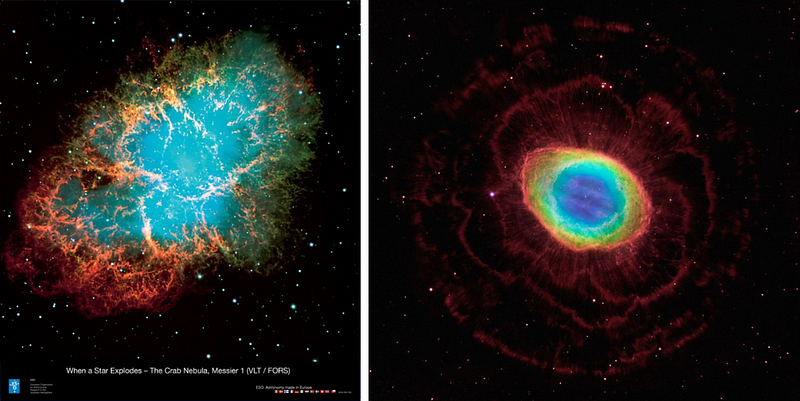

The hypothesis is known as panspermia, and while there are crazy people out there who’ve taken this idea and run with it (you can find all sorts of insane rantings on the internet about it), there is some legitimacy behind the idea. You see, the Earth was not the first thing to form, but came about after legitimately over nine billion years of cosmic evolution. The entities that give rise to our planet were previous generations of stars that ended their lives in planetary nebulae, supernova remnants, and even neutron star-neutron star mergers, all of which sent heavy elements back out into the Universe.

In many cases, those heavy elements were bound together in tremendously interesting molecular configurations, configurations that we see today as truly “organic” matter.

When meteorites land on Earth, like the Murchison meteorite, shown below, we can analyze what’s present inside. Yes, we find all sorts of interesting organic molecules, but what’s perhaps most interesting is the amino acid content. While there are only about 20 amino acids that play a role in life processes here on Earth, there are nearly 100 unique amino acids found in this meteorite, a strong indication that the ingredients for life are ubiquitous throughout the Universe. We even find amino acids on the Moon, indicating that whatever brought these ingredients to Earth did so before the formation of the Moon, less than 100 million years into the age of our Solar System!

Well, if the ingredients are there, why couldn’t some primitive form of life be there as well? If all life on Earth has a universal common ancestor, couldn’t it be that there are many forms of ultra-primitive life in the Universe, and the type that came to Earth that was best adapted to the early Earth’s environment was the type that thrived, evolved, reproduced, and out-competed all the others? We don’t have enough evidence to favor this hypothesis over any other, but if we continue to push this limit back earlier and earlier: 4.3 billion years, 4.4 billion years, 4.45 billion years… it’s going to be harder and harder to argue that this life didn’t come to Earth already alive in some sense.

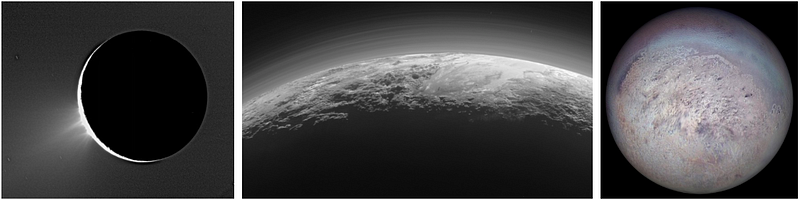

It’s possible that the geysers of Enceladus, the “black smokers” on Neptune’s moon Triton or even the snow-and-ice features of Pluto contain these primitive forms of life, and that it was bombardment by comets and other Kuiper Belt objects that brought an early, primitive form of life here to us. The best part about a hypothesis like this is that we can test it today, if we decide to send a mission (even an uncrewed mission) out to these worlds and check it out.

That’s the beauty of science: if you have an idea, all you need to do is test it out, and then you know. When it comes to the origin of life on this world — and the possible implication that it’s everywhere — wouldn’t you want to know the truth?

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!