Tribalism and an urgency to act: what Ukraine and climate change have in common

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a tragic example of what is wrong with humanity.

- The recent IPCC report on climate change is another.

- Taken together, they make it clear that time is running out for humanity to act. We must embrace a new moral ground where we see each other as members of the same tribe: the human tribe.

Given the tragic situation in Ukraine, it’s hard to write about a specific scientific topic this week. My ancestors came from there, having immigrated to Brazil in the early 1900s to escape Bolshevik attacks, in particular against Jewish settlements. One hundred years later, the geopolitical situation is quite different. We see a Russian leader and his supporters desperately trying to hold on to a grandiose past that is no more. Still, it is Russia invading a neighbor again, forcing hundreds of thousands of women, children, and the elderly to seek refuge in Poland, Romania, and other friendly neighbors. Men under 60 were ordered to stay and fight for their land, many of them with little to no experience in combat. They enlist to defend their land and their families. Meanwhile, millions of people across the world march the streets to protest the situation. Tragically, this story has played out over and over again across the centuries. What is it about humans that drive them to this mutual aggression?

Far be it from me to propose a solution to this complex cross-disciplinary question. There is greed, the lust for power, the need to control resources, and the belief that more is better. But I would like to call attention to another essential aspect of the question: our deep-rooted tribalism, the cultural and psychological tendency humans have to choose tribes to belong to, while excluding those who do not make the same choices.

The triumph and tragedy of tribalism

“Belonging” is a key word here. It has its origins in our tribal past, when groups of individuals would struggle and fight for survival in adverse environmental conditions. To belong to the tribe meant protection from outside aggressors and an immediate sense of identity. I am part of a group that shares my values. Being part of this group makes me strong. Those who are not part of my group, who do not share my values, are a threat. They are the enemy. If we do not destroy them, they will destroy us. We thus must convert others to our value system or, if that fails, destroy them by any means available.

There are gradations of tribalism, of course. Only the most extreme would adopt the those-who-do-not-belong-are-enemies value system, and only the most aggressive within these will opt to destroy their opponents. Most tribes actually feed on each others’ strength and motivation to pursue a common goal. In his book Tribe, Sebastian Junger argued for the importance of such socially bonding values, citing the detribalization of modern life as a cause for our current social and political misdirection. Tribalism can play a positive role in society and has been key to our survival.

However, taken to its extreme, tribalism is divisive, prejudiced, small-minded, and, as we see every day in the news, deadly. Most extreme tribal behavior springs from a perceived threat to what the group believes are sacred values or beliefs. “Sacred” here does not necessarily imply religious values: “secularized sacred,” as anthropologist Scott Atran has argued, can play a key role as well, as in political notions of “human rights” or in ideologies that attempt to “save humanity” through political revolution (e.g., socialism, anarchism, communism, fascism).

What do we mean by tribe?

It is important to contextualize what I mean by “tribalism,” given that the term can be contentious. The word “tribe” is usually defined as “a social division in a traditional society consisting of families or communities linked by social, economic, religious, or blood ties, with a common culture and dialect, typically having a recognized leader.” It also shares the same Latin root as the words “tribune” (literally head of a tribe) and tribunal.

Although in historical contexts the word tribe is broadly accepted (the area was inhabited by Slavic tribes or indigenous tribes of the Amazon), in contemporary contexts, it is often problematic when used to refer to a community living within a traditional society. The problem arises from it being strongly associated with past (and current) attitudes of white colonialists toward so-called primitive or uncivilized peoples living in remote “undeveloped” places. It also can carry derogatory connotations, as one group of people referring in offensive ways to another. For this reason, it is generally preferable to use alternative terms such as community or people.

However, I am using the word precisely because it is important to attract people to this conversation and explore the issues at hand. The words tribe and tribalism are used extensively in current events to describe the acute polarization in modern American society and across the world. Tribes unite and protect those within but erect barriers and ostracize those outside. The very notion is an obstacle for political and social justice and needs to be addressed in an openminded and morally progressive way.

The paradox of tribalism

There is a paradox here, as we humans need to belong. We are social animals, and being part of an identifying group is essential to a healthy emotional life. We experiment with such tribal behaviors all the time, from joining cliques in junior high school to being sports fans with painted faces. Sometimes such experiments get heavy and violence erupts. Growing up in Rio, I remember as a kid how ferociously I defended my local soccer team. Anyone who didn’t support my team was at least suspicious, if not plain mad. How could their value system be sound if they chose to support another team? And how different is this from the current polarized behavior in American politics? They are different tribes, with different value systems, vying for power.

Tribalism is deeply ingrained in our value system. There is no way out of it. We need it; we love it; we hate it. What leads to extreme behavior, however, is something else. Extreme behavior comes from a radicalized sense of belonging, a desperate attachment to a single-minded goal that causes a shortsightedness about the “other.” Extreme behavior is inward-looking, intolerant, and unwilling to grow or to look outward. The need to belong swallows any other value system, even the value of one’s own life. Leaders feed on the devotion of their followers; followers feed on the devotion to their leader and the cause he/she represents. Fear plays a key role in inducing tribal entrenchment.

After millennia of agrarian civilization, we remain morally stuck in our tribal behavior. Buddhists teach that detachment is the way to inner peace, that the root of all ill comes from our attachment to things, values, and people. This is a hard lesson to learn for most of us, but if we connect a level of detachment to openness, we may have a chance to move on. We can commit to goals without radicalizing them and to support certain groups without demonizing others. We can follow value systems without closing off to different choices that others make. Red Sox or NY Yankees, we all share the same playing field.

Our one human tribe

Just this week, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its bleakest warning yet: “This report is a dire warning about the consequences of inaction,” said Hoesung Lee, Chair of the IPCC. “It shows that climate change is a grave and mounting threat to our wellbeing and a healthy planet. Our actions today will shape how people adapt and nature responds to increasing climate risks.”

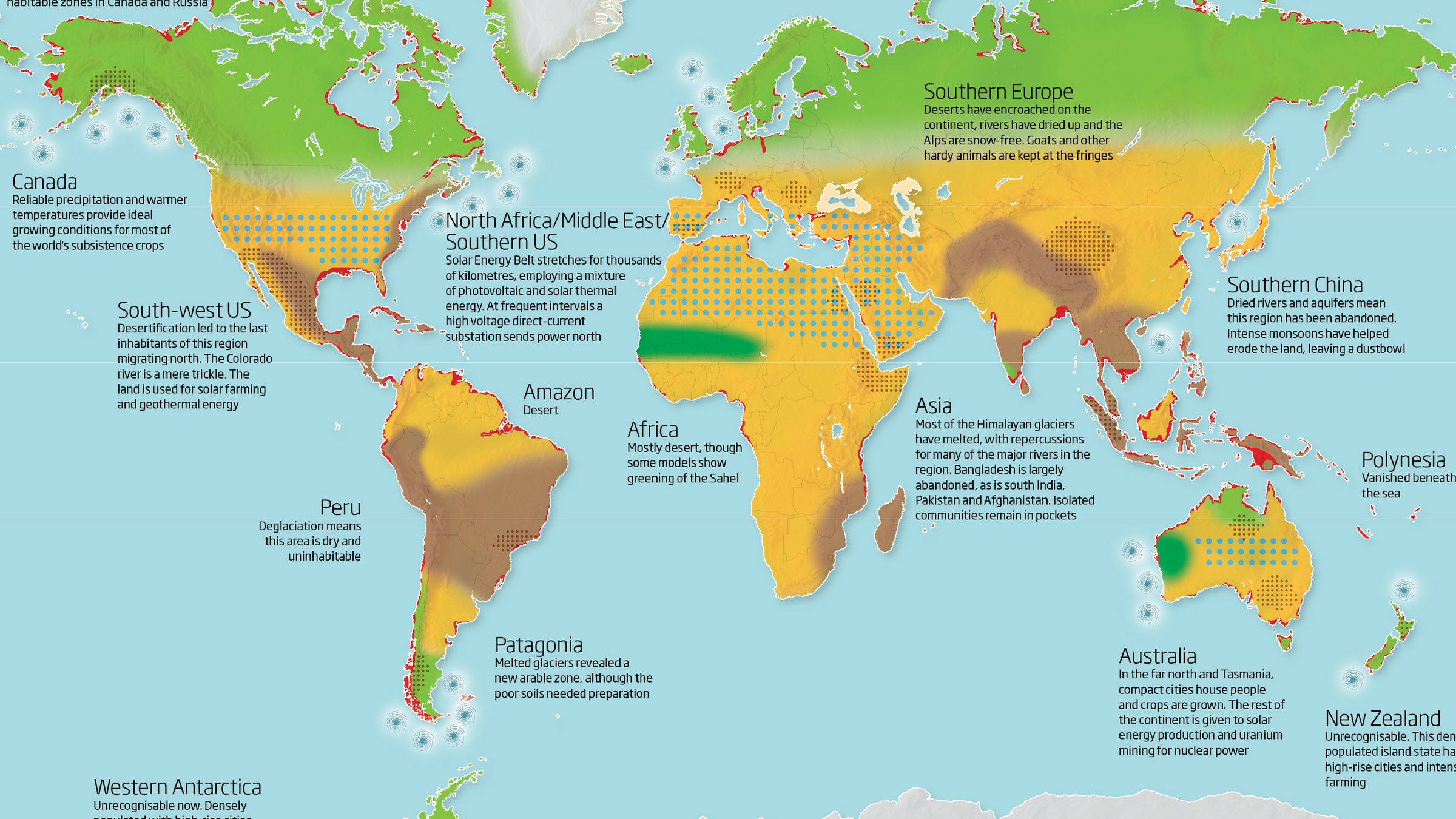

Why do I bring global warming into this discussion about tribalism? Because global warming is a crisis that involves all of humanity and Earth’s ecosystems. It is a challenge at a global scale, the likes of which we have never faced before. It also makes it clear that, despite our tribal divisions and sectarianism, climate change forces us to think as a single tribe — the tribe of the human species. This is a call to action that goes above and beyond geopolitical confrontations, as does the COVID-19 pandemic. A virus sees no borders.

It is high time humanity starts to rethink itself, to rethink our role on this planet. If we are to contemplate a future for our children and grandchildren that is at least as comfortable as our present, we need to retell the story of who we are — not as tribe fighting tribe to the death, but as a single tribe that respects and cherishes cultural and ethnic differences, that is open to learn from each other, and that respects all forms of life, human and otherwise. Taken together, the war in Ukraine and the new IPCC report make it clear that we don’t have much time left.