James Webb Space Telescope launches astronomy into a new era

- It all started with astrology, as our ancestors tried to decipher messages from the skies.

- The same human impulse to know its origins links the ancient Babylonian Tablet of Ammisaduqa with the James Webb Space Telescope.

- The urge to understand our place in the Universe remains as alive as ever.

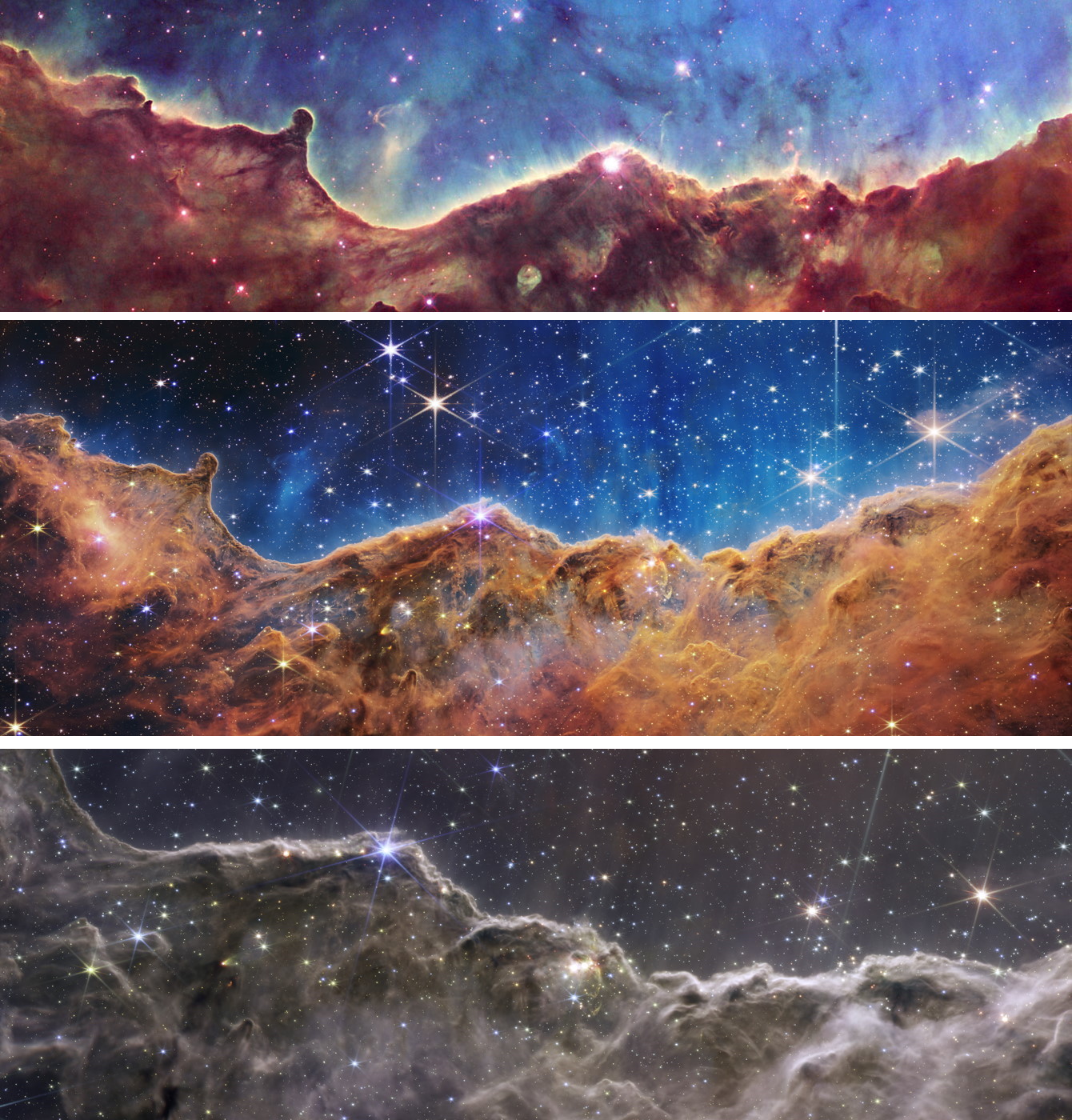

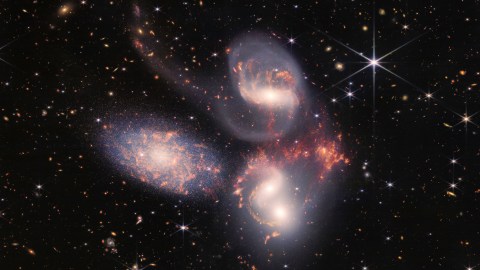

The James Webb Space Telescope has given us its first images, and they are spectacular.

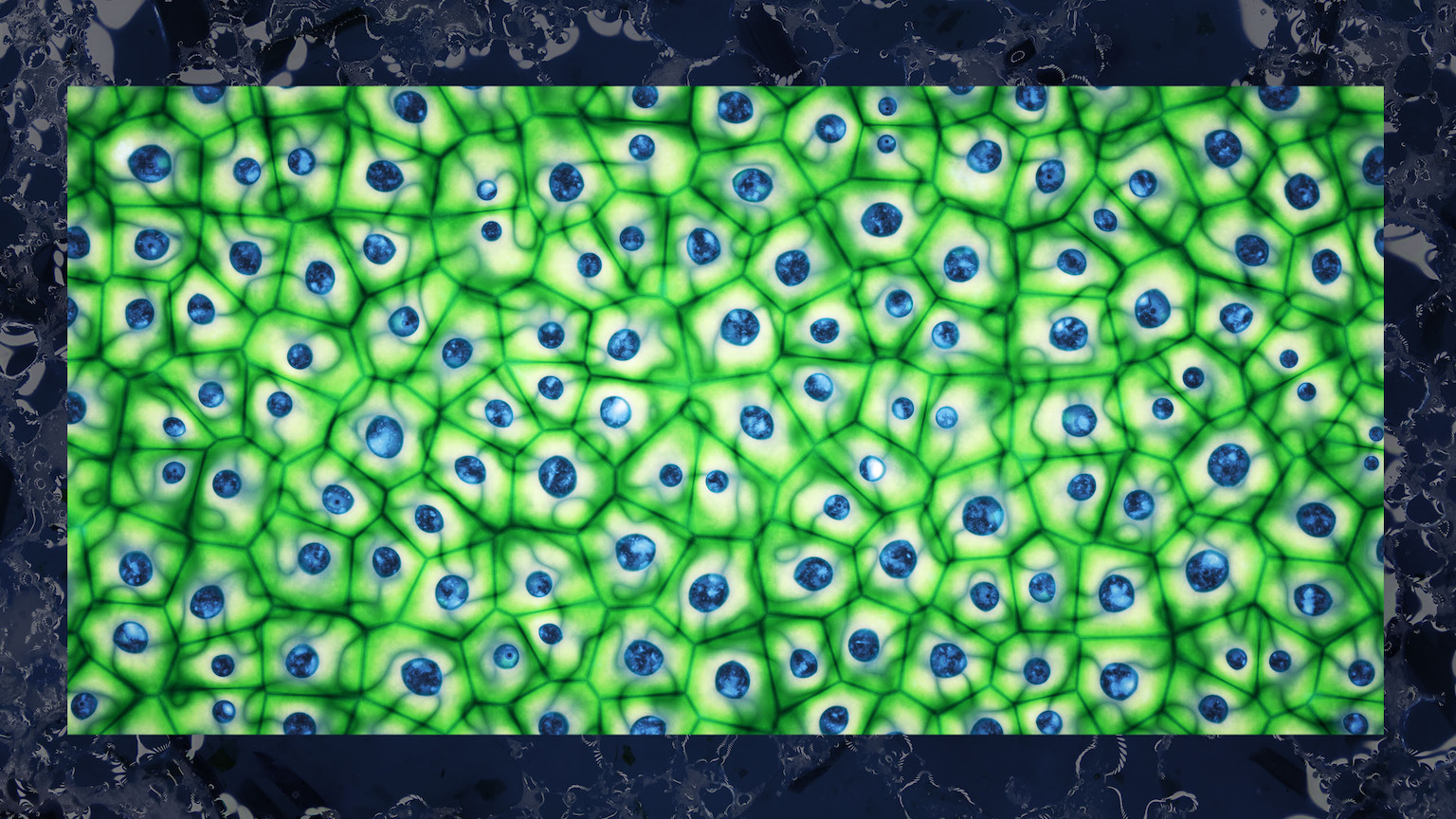

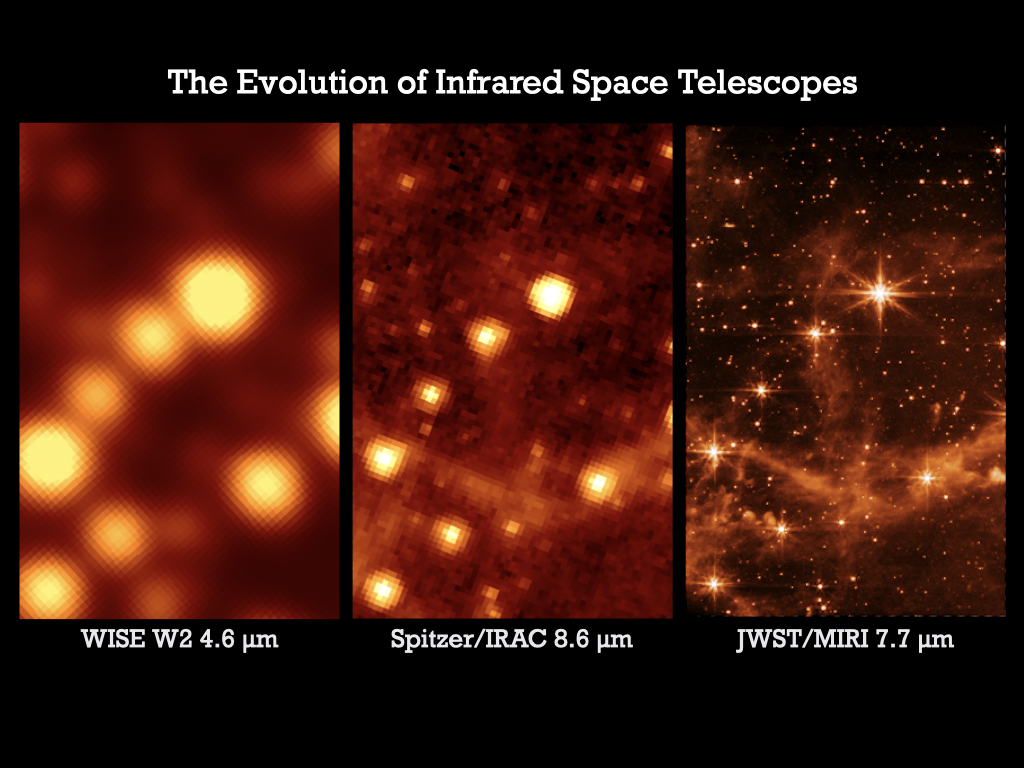

We covered the telescope’s launch in these pages. Now that we can view its first shared work, we can say without any hyperbole that astronomy has entered a new phase. It is a phase that will cover both ends of the Universe’s greatest enigma: the existence of life, here and possibly elsewhere. I say “both ends” because the telescope has two main complementary missions. It will look at the first stars — the earliest agglomerations of hydrogen that about 13 billion years ago started to churn up all the chemicals that make up planets and, at least here, living creatures. It will also analyze the atmospheric composition of exoplanets — worlds that orbit stars far away from us — searching for signs of life.

This is quite a milestone, and none too shabby for primates with enlarged brains that only 20,000 years ago were hunting and gathering to survive. Our distant ancestors looked up at the skies with a mix of awe and fear, not knowing why things happen the way they do. The moon and its phases, thunderstorms, solar eclipses, comets, shooting stars, and rainbows — was there a meaning to this celestial display? Were the skies trying to tell us something? As the James Webb Space Telescope begins its work, it is worth revisiting these origins.

From humble beginnings, we have come far

Hundreds of millions of people read their horoscopes every day. They are hoping to find some kind of answer to the worries in their lives, as if the Cosmos speak directly to each one of us. Would it not be wonderful if indeed the Cosmos guided us in this way, giving us answers to life’s troubles and tribulations, directions coded in the arrangements of planets and stars?

Astrology has been the main motivation for astronomy at least since the earliest agricultural gatherings along the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers in the Middle East, and probably even before that. Take as one example the Babylonian Tablet of Ammisaduqa. Dating from about the mid-17th century BCE, it recorded the risings and settings of Venus for a period of 21 years.

The same human impulse to know our origins links the Tablet of Ammisaduqa with the James Webb Space Telescope. And since Galileo pointed his telescope at the sky in 1609, the human understanding of the Universe and all its creations has grown exponentially. Galileo saw mountains and craters on the Moon. He saw that Jupiter has its own moons, that Venus has phases, and that the Sun has spots. These discoveries added complexity to a Cosmos that for thousands of years had been simple and immutable, with all celestial luminaries made of ether, a substance supposed to belong only to the heavens.

We now know that the same laws of physics and chemistry apply across the Universe, and that the stuff that makes the stars is the same stuff that makes worlds, even if it is organized in different proportions. This universality of the laws of Nature makes the study of distant regions of the Universe possible, bringing the Cosmos within our reach.

The temples of astronomy

The stars are distant and unreachable, yet we feel a deep connection to them. In the modern scientific attempt to study the skies, we identify the same longing for meaning that drove our ancestors to look up and worship the gods. Our amazing space telescopes, and also our terrestrial ones — such as the ALMA facility operated by the European Southern Observatory in Chile, or the cluster of amazing telescopes atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii — are testimonies to our modern urge to continue to decipher the heavens. We know the answers are up there, waiting.

We now know that we are made of star stuff, linking our origins to the rest of everything that exists in the Universe. To know the Cosmic history is, in a very real sense, to know our own. As we trace our material origins to the Cosmos, we bridge our existence, our individual and collective history, to the Universe at large.

Our predecessors looked up at the skies trying to make sense of powers well beyond their reach. And despite the challenges and complexity, we never gave up trying to understand. That we can now tell large parts of this story, linking the very early times after the Big Bang to our own existence, is nothing short of wonderful. We owe our deepest gratitude to the scientists and engineers responsible for the design of the James Webb Space Telescope and its successful deployment. Our temples now float in space, their eyes trained at the distant stars.